Jo Siffert was an easygoing, impulsive racer. At times situations upset him, but there was never any side to him. He spoke his mind, said what needed to be said, and then it was forgotten. He was too competitive to make close friends with his rivals, but his friendships away from racing were strong. The sculptor Jean Tinguely also came from Fribourg, and when he died just before this year’s Italian GP, his funeral emulated Seppi’s through their native streets.

“Jean was a good influence developing Seppi’s mind beyond motor racing,” says Deschenaux. “He would often arrange his own calendar around Seppi’s racing commitments.”

“15,000 people turned up for the funeral and Jean’s cortege followed the same route. He wanted people to be emotional, but not sad. Seppi’s funeral had been so sad. After Jean’s ceremony all of the people were fed — there was a fantastic spirit.”

Winning was everything to the spontaneous Siffert, the man who brought Marlboro into F1, but Mader remembers: “Seppi took his racing seriously but liked to laugh and have fun. He didn’t ever want to turn into some sort of sad professional.”

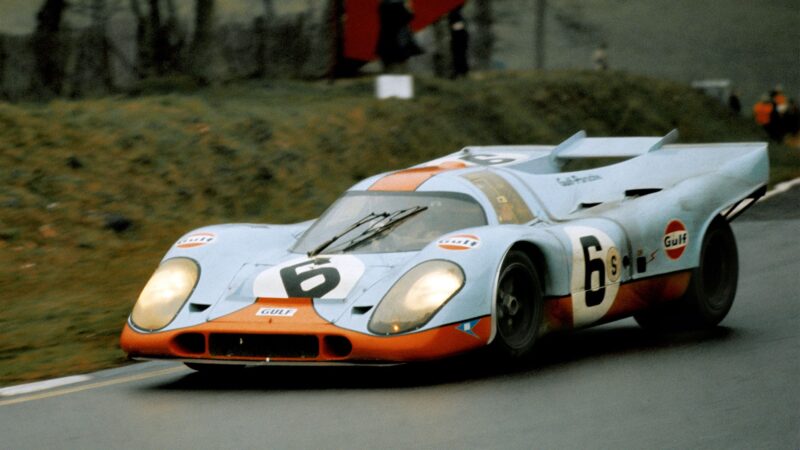

One of Deschenaux’s stories encapsulates Siffert’s racing philosophy. “At the 1971 Spanish GP I arrived in Barcelona on the Friday at six in the evening and Seppi, of course, was already there after first practice. He said: ‘Come with me. No questions,’ and rushed me to Porsche’s private plane. We flew to Le Mans and the next day he calmly took part in the April test and hit 400km/h on the Hunaudieres in the 917, before we jumped back into the plane and flew back for the final practice in Barcelona! There was never enough driving for him!”

Siffert also made his name in sports cars, seen here driving a Porsche 917 for JWA at Brands Hatch in 1971

DPPI

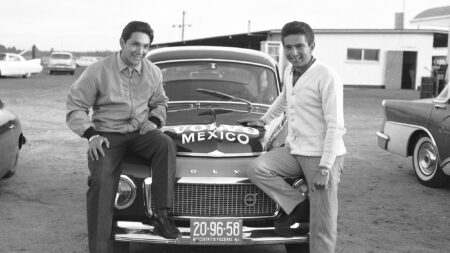

From motorcycles he graduated to Formula Junior, then F1 with a 1500cc engine in his Junior Lotus. It was clear he was quick, and when the organisers of the American and Mexican GPs in 1964 refused him an entry unless he could align with a team such as Rob Walker’s, a fresh die was cast.

“Seppi was one of my greatest friends,” says Rob without hesitation. “We used to have such parties together. At the opening of his garage in Fribourg we had a rip-roarer until five in the morning, and then by six thirty he was off on work somewhere.

“His first race for me was Watkins Glen in 1964 alongside Jo Bonnier. He finished third. I was highly impressed and signed him for 1965.

“At Goodwood that April he had this dreadful accident when he thought the whole of the chicane was movable but only half of it was and he hit the other half, which was brick. He kept complaining about a stiff back, and it turned out that if he hadn’t been on his back the whole time he’d have been paralysed. He had damaged a vertebrae but initially the doctors had told him to stop moaning. He was determined to be ready for Monaco and wanted to get back home to his own doctor.

“Having learned it all from Stirling I could tell Seppi and he’d listen” Rob Walker

I followed the ambulance to London Airport and there this enormous matron looked at this skinny little driver and said: ‘Did you have a little accident on your bicycle over the holiday weekend?’ Seppi’s English wasn’t very good then and he just smiled at her, but then the head of Swiss Air arrived and threw up his hands and told him he had cleared the whole aircraft for him, the whole back end. The matron was just amazed. The man was bowing to Seppi, whom she had thought was just a boy. It was one of the funniest sights, her eyes were popping out!

“The great thing was that having had Stirling in the team I had learned everything I knew from him. Before him I had had no experience. Having learned it all from Stirling I could tell Seppi and he’d listen.

“At Syracuse Stirling always said that if you got a break, just go for it. Seppi led John Surtees and Jimmy Clark there in April 1965 and there was a fast corner after the pits which it was just possible to take flat. Bonnier managed to let Seppi through before it as they lapped him, and then held them up a little. With a two second lead Seppi really went for it and was pulling away until he jumped too high over a brow 10 laps from the end and the engine blew when the car jumped out of gear.”