The man who made iRacing: Dave Kaemmer’s smash hit

A photographer would need special press accreditation to get this close to the action but in esports the possibilities are endless. Preston Lerner traces the history of the motor racing simulator and how one American’s drive for near-real perfection has led to an online racing phenomenon that even attracts top drivers and teams

For those brought up on Commodore Amigas and ZX Spectrums, this in-game image from the 2020 IndyCar iRacing Challenge Chevrolet 275 may be an eye-opener.

“Dave Kaemmer is God!!!” Such was the overheated fanboy title of a thread that appeared more than a decade ago on Race Sim Central, a site that catered to the first generation of hardcore virtual racers. But in the years since, Dave Kaemmer has – astonishingly – graduated to even-more-mythic status as the co-founder and principal software guru of the online-racing leviathan iRacing.

“In my opinion, he founded the sim-racing genre,” says Tim Wheatley, who created the original Race Sim Central website and recently revived it. “I can’t overstate how important he is.”

Racing games have been a lifelong project for Kaemmer, a wiry, well-preserved 57-year-old resident of suburban Boston, Massachusetts. He was there at the birth of racing simulations for the masses, and he now stands at the pinnacle of what has improbably matured into a legitimate sport.

“It’s way beyond what I imagined it could get to,” he admits. “I look at the game today – and I call it a game because it is fun even though we didn’t set out to make it fun – and it blows me away because it is just like being in a race. For real racers, the greatest fear is not physical harm. It’s being slow. And that fear is definitely there on the computer.”

Mexican NASCAR driver Daniel Suárez raced in the eNASCAR iRacing Pro Invitational Race in 2020 at a virtual Texas Motor Speedway

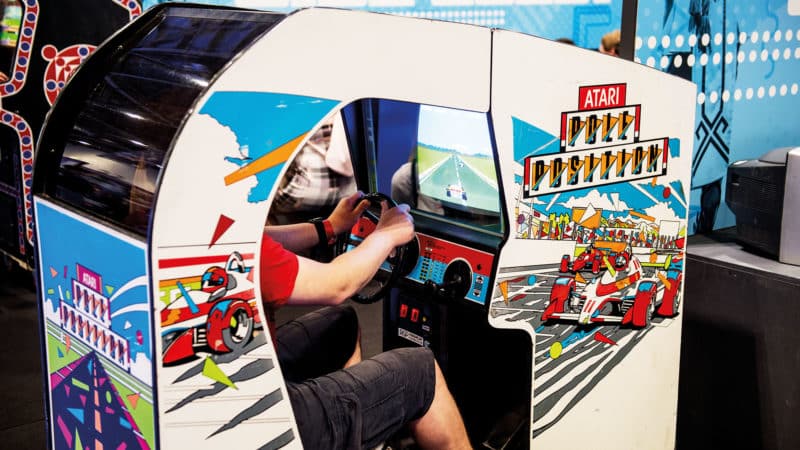

Atari racing sim Pole Position arrived in 1982 and within a year was the world’s most popular coin-operated arcade game

Dave Kaemmer’s involvement with motor racing simulators led him to try out the real thing

Millennials and members of Gen Z have never known a day without high-fidelity racing video games. So it’s worth noting that the first title to feature a real-life circuit didn’t debut until 1982 – Pole Position, a monstrously successful and influential arcade game that replicated Fuji Speedway in blocky two-dimensional graphics in the Space Invaders/Pac-Man idiom.

Kaemmer graduated from Oberlin College in Ohio in 1985 with a degree in mathematics because it didn’t offer a computer-programming course. After a couple of years unhappily writing business and educational software in Boston’s Route 128 technology corridor, which was emerging as an East Coast version of Silicon Valley, he and a friend flew to California to pitch Electronic Arts with a proposal for a flight simulator program. No sale. Instead, EA asked them if they could create a video game simulating the Indianapolis 500.

As it happens, Kaemmer had grown up in Indiana, where, as he drolly puts it, “Memorial Day was Race Day. The Indy 500 was always blacked out on local TV, but I could listen to it on the radio. I remember being at a picnic one Memorial Day, and my family was having a good time at the lake while I was sitting in a hot car, listening to the radio, because Tom Sneva was racing, and he was my guy.”

Kaemmer reverse-engineered race tyres to improve sim accuracy

The major weakness of racing games of the day was that they featured a top-down perspective. To enhance realism, Kaemmer opted for an immersive first-person perspective, à la Microsoft Flight Simulator, and by writing in assembly language and performing all sorts of coding sleights of hand, he was able to produce 3D graphics that seemed positively magical at the time.

But Kaemmer was a software engineer rather than a race engineer, and he knew nothing about the technical side of motor sports. Carroll Smith’s book Tune to Win became his bible, with Race Car Engineering Mechanics by Paul Van Valkenburgh filling in the gaps. The hardware limitations of the day – typically a mere 512K of RAM – translated into primitive vehicle dynamics, with the cars moving unrealistically along x-y axes. Nevertheless, the game allowed players to make set-up changes, and the car-damage model made the crashes even more entertaining.

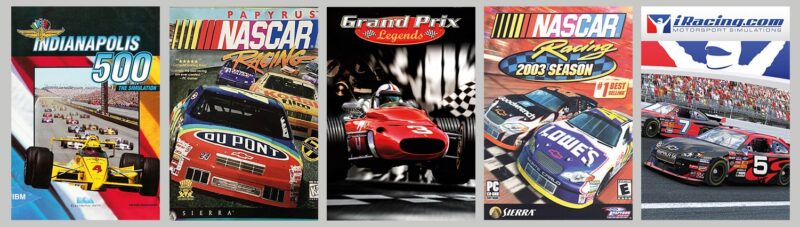

When it appeared in 1989, Indianapolis 500: The Simulation was the first legitimate racing sim to reach the market, and it sparked a revolution. In the UK, Geoff Crammond would achieve cult status among simheads with his series of addictive Grand Prix games. In the States, Kaemmer’s company, Papyrus Design Group, dominated this space with a pair of IndyCar titles and then a run of ever-more-realistic – and profitable – NASCAR games.

Papyrus’s Indianapolis 500: The Simulation from 1989 was a full sim of the race with 33 cars

virtual Darlington Raceway in South Carolina for the eNASCAR iRacing Pro Invitational Series race in May. It was won by Erik Jones

spot the cars racing at a packed virtual Bristol Motor Speedway in Tennessee for the eNASCAR iRacing Pro Invitational Series race

From the beginning, Kaemmer was badgered by critics who claimed that his cars were too hard to drive. Gamers were accustomed to be able to master games like Forza or Gran Turismo in a couple of sittings, and even the Crammond Grand Prix titles could be enjoyed at a recreational level by entry-level players. But Kaemmer’s masterpieces, then and now, can be studies in frustration requiring an intimate familiarity with the reset button.

“We say here at iRacing, ‘We don’t care if it’s fun or not. We care if it’s real,’” he says. “We spend a lot more time trying to figure out if the numbers correlate with the real world. If you try to make an actual simulation of driving a race car, which we do, it turns out that beginners spend a lot of time spinning. Sometimes, we’ll err on the side of maybe this is a little bit too difficult. But we’re always trying to get the numbers right.”

In the late 1990s while working on Grand Prix Legends, Kaemmer enrolled on a Skip Barber Racing course and began competing

Although the NASCAR titles sold in large numbers, Kaemmer was hungry for something more challenging than stock cars pounding around ovals. He found inspiration in a book he’d received as a Christmas present a few years earlier – The World Atlas of Motor Racing by veteran Formula 1 journalist Joe Saward. Kaemmer wanted to recreate the Nordschleife, the original Spa and other fearsome tracks that had been de-fanged in the interest of safety. Better still, he decided to do it with the 3-litre, non-wing, pre-slick-tyre F1 cars of 1967.

Grand Prix Legends, published in 1998, was the most ambitious racing sim ever released, and not just because it channelled a golden age of Formula 1 racing. GPL, as it’s known to its obsessive devotees, was the first game to authentically simulate vehicle dynamics from dips and camber on race circuits to the effects of rotating engines and spinning wheels. The software underpinning GPL also allowed for multiplayer racing over the internet in the days of dial-up service.

“We set up a server in our office, and we got 128 phone lines, and we connected them to modems,” Kaemmer recalls, “Right away, all 128 phone lines were jammed. We’d get calls from parents who said, ‘My son just got a $750 phone bill last month!’”

Grand Prix Legends from 1998 was set in the 1967 F1 season. Due to its realism, it was a tough game to play and sales were poor. Those that mastered GPL could enjoy the most sophisticated sim to date.

Lamentably, GPL was a commercial flop for a variety of reasons, most notably because the subject was so obscure to Americans and the cars were so diabolically difficult to keep on the track – even leaving the pits! (It continues to enjoy cult status, thanks to ‘modders’ who have used it as the basis for games revisiting everything from the 1955 F1 World Championship to the 1971 Can-Am series.) After working on a few more NASCAR titles, Kaemmer left Papyrus to pursue other interests. One of them, not so coincidentally, was real-world racing.

While working on GPL, Kaemmer had gone through the three-day programme at the Skip Barber Racing School at Lime Rock Park in Connecticut. Buoyed by this experience, he started competing in the arrive-and-drive spec series promoted by the school, which featured open-wheel tubeframe cars not unlike Formula Fords.

Kaemmer figures he entered about 100 races at many of the premier American tracks, winning 19 of them. “He was extremely good in a real race car,” says Divina Galica, who entered three Formula 1 World Championship races in the 1970s before working as a Skip Barber instructor and later joining Kaemmer at iRacing. Kaemmer’s crowning moment was driving a Porsche 996 GT3 Cup in the Daytona 24 Hours in 2007.

“It was great, it was really eye-opening, but it was stressful,” he says. “I got to the point where I felt like if I spent some more money on racing, it would get increasingly dangerous, or I could pursue the gaming thing, and that seemed like a better way to spend my time.”

Code from Papyrus’s NASCAR Racing series became the basis of iRacing.

By then, Kaemmer had partnered with John Henry, an immensely successful American businessman who owned the Boston Red Sox baseball team. (He would later buy Liverpool FC as well.) Henry was also a huge NASCAR fan; he currently co-owns Roush Fenway Racing. Playing Kaemmer’s NASCAR racing game in an online league had convinced him that sim racing could be something more than a geeky pastime. As he explained back then: “I want to create the sport of virtual racing.”

Kaemmer and Henry launched iRacing in 2008. At the time, it featured eight cars controlled by a modified version of the source code for NASCAR Racing 4, Kaemmer’s last game before leaving Papyrus, and 22 laser-scanned North American racetracks. (It’s now up to more than 100 cars and 100-plus tracks.) Because the digital circuits are virtually 100% accurate, they’re used as training tools by everybody from lowly club racers to top-shelf pros.

From left: Indianapolis 500: The Simulation (1989); NASCAR Racing (1994); Grand Prix Legends (1998); NASCAR Racing 2003 Season (2003); iRacing.com (2008)

Looking good is all very well, of course. But the essence of any racing simulator is the accuracy of the vehicle dynamics. Kaemmer and his crew have steadily upgraded the car physics over the years through input from real-world racers and teams as well as several former engineers who are now on the iRacing staff.

Kaemmer himself remains fanatically focused on where the rubber hits the road – that is, the contact patch. “He’s a genius at developing the tyre model,” Galica says. Adds iRacing executive vice president Steve Myers: “He’s doing things with the tyre model that even tyre manufacturers don’t attempt to do.”

Tyre companies remain highly secretive about their products. But by deconstructing used race tyres, Kaemmer has reverse-engineered how they’re put together and can convincingly predict how other shapes and sizes ought to work. “We describe the tyre in a sort of simplified rubber recipe, the way the tyre compound would work,” he says. “Then we construct it the way they would lay up a tyre on a drum to build it, specifying cords and angles and all this stuff. And at the end of the day, the model can crunch all that and give us the numbers that we need.”

Members can choose from more than 100 cars at iRacing

But even more than the accuracy of the tyre and physics models and the realism of the circuits, the factor that has transformed iRacing into a global phenomenon is the ability to race – virtually – against other human beings within a framework of rules governing action on and off the track. For those who haven’t tried it, it’s impossible to understand how immersive the experience is. The cars may not be real, but the racing most definitely is.

Dale Earnhardt Jr was one of the high-profile early adopters. On Sunday nights, after finishing a NASCAR Cup race, he would often enter an iRacing race to de-stress. Today, 23-year-old William Byron, who drives the No24 Chevrolet Camaro for Hendrick Motorsports, is the poster boy for a new generation of racers who’ve spent more time learning their craft on iRacing than they did on kart tracks.

Although Kaemmer and Myers obviously don’t want to crow about it, the Covid pandemic has been a huge windfall for iRacing. With no live racing permitted in the United States, NASCAR and IndyCar dipped their toes into the esports world by partnering with iRacing to produce virtual races featuring driver rosters of series regulars. Unbelievably, the races attracted more than half the audience that normally would tune in to TV broadcasts of real racing.

Lando at Indianapolis…

IndyCar’s Simon Pagenaud and Norris collide at the IndyCar iRacing Challenge First Responder 175 at the virtual Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 2020

Prominent iRacer Rajah Caruth, 18, is making the transformation from screen to track as part of NASCAR’s Drive for Diversity Driver Development Program

Even though motor sports has returned to a semblance of normality since then, iRacing’s footprint continues to grow. Since January, the subscriber base has jumped 54%, from 110,000 to 170,000. “We’ve turned into the Coke of the space,” Myers says. “People don’t call it sim racing; they call it iRacing. I can’t go 10 feet in the NASCAR paddock without being stopped by a fan or a crew chief or a driver. It’s become part of the fabric of the sport.”

Has sim racing reached the promised land? Well, work is still being done on the margins with virtual reality and enhancements such as racing in the rain. But the graphics are nearly perfect, and the physics are about as good as they’re going to get. “In some ways,” Kaemmer says, “I feel we’re kind of done.”

On the seventh day, God rested.