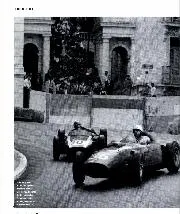

As time has passed, the essential facts of that 1961 season have tended to become rather juggled around. True, Stirling Moss worked miracles with the little four-cylinder Lotus 18-Climax belonging to Rob Walker but Hill is emphatic: “Many, many times I’d have willingly traded my Ferrari’s power for Moss’ handling. That Ferrari was absolutely awful round circuits like Monte Carlo. It was nothing but a truck and I would have dearly liked the handling of that little Lotus”. Whilst in no way disputing the brilliance of Stirling Moss, one senses that Hill feels very earnestly that there was a tendency for people to think “anyone can win with a Ferrari” and he disagrees strongly. (Ferrari actually said this!)

Phil Hill only won the Belgian and Italian Grands Prix, although he took second place behind von Trips at both Aintree and Zandvoort, and there was obvious disappointment waiting for America’s first World Champion when Ferrari decided not to take part in the United States Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. “I really didn’t get a lot of pleasure out of that Championship season”, Hill told us, “because the 1960 season was much more satisfying. There was a good deal of backbiting in the team in 1961—remember we had Ginther, Trips, Baghetti and Ricardo Rodriguez. Then, of course, came 1962 and we had virtually no results at all. That proved what a bad chassis the Ferrari really was”.

Hill heads Jim Clark at Zandvoort in the former’s championship year of ’61

Getty Images

By the middle of the 1962 season, Hill’s sensitivity was bringing him to think he couldn’t stay at Maranello any longer. He also found relations with team manager Tavoni rather tense. Phil used to talk openly to certain journalists and Tavoni used to upset him by confronting him, take a button of Phil’s shirt between finger and thumb and almost pull it off as he said “Pheel, you are spoke too much . . .” Hill muttered “Goddam; that damn Tavoni—pulling the buttons off my shirt!” “They built up a new car for me with a wider track and the clutch mounted inboard of the gearbox to replace the arrangement whereby we had the clutch right out at the back of the gearbox. That car could never pull the same revs, as we’d seen in 1961 and it was virtually impossible to haul round tight corners. You had to use some real funny antics to get it round the slow corners at Monaco, although it wasn’t too bad in the closing stages of that year’s Monaco Grand Prix because the rubber was well worn and a little bit of rain meant that it was easier to swing round the turns. That’s why I was closing in on McLaren’s Cooper towards the finish”.

Despite the odd promising performance, Ferrari could see his cars being beaten by their British rivals. He decided the responsibility lay firmly with the drivers and was not impressed by their remonstrations about the car. Hill by now “absolutely desperate to get away from Ferrari” moved along with his team-mate Giancarlo Baghetti to the newly-formed ATS team for 1963.

The ATS organisation was formed by a number of Ferrari “breakaways” including current-day Autodelta team director Carlo Chiti. Their plan was to build a new Italian Grand Prix car to beat Ferrari at his own game; and their efforts failed miserably. Although neither Hill nor Baghetti scored a single Championship point during the course of that disastrous season, Hill remains reasonable and charitable when recalling the project. “They’d all gone off from Ferrari to build this ATS and, while there’s no doubt it was an extremely ambitious effort, it was considerably misjudged. Also, it must be remembered that Italy was going through probably its first big post-war financial crisis at the time and events just overtook them. Really, it was a marvellous little engine that ATS V8, even though it suffered from the most incredible oil surge problem. You could almost feel the whole thing lose revs as the crankshaft became swamped with oil!”