Behra, born in Nice in 1921, was one of life’s natural competitors, racing bicycles, then motorcycles, in his teens until the war intervened. Afterwards he carried on as before, champion of France for several years on his red Moto Guzzi. A move to cars, though, was increasingly in his thoughts: by the end of 1951 he had turned his back on bikes and headed to Paris, to 69 Boulevard Victor, where resided the team of Amedée Gordini, whose cars were sometimes fast, always fragile. A contract was signed.

The following June Behra broke into the national consciousness, and he would remain an idol in France for the rest of his life. At Reims, totally against expectations, he defeated the Ferrari team in the Grand Prix de la Marne, fighting off even Alberto Ascari.

“It was impossible,” said Jabby Crombac, “to overstate the importance of that victory in France. It was only two weeks after Le Mans, where [Pierre] Levegh tried to drive the whole race on his own, and failed at the very end – leaving victory to the Germans! This was not so long after the war, you know…

“Wimille and Sommer were gone, so when Jean – who was new in car racing – won at Reims, he was instantly a national hero. Beating the Italians was almost as good!”

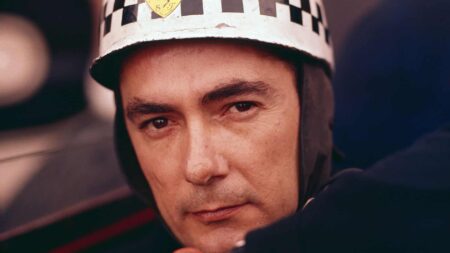

Louis Rosier leads Jean Behra, who would go on to win, at Reims in 1952

Heritage Images/Getty Images

Crombac adored Behra: “He was like Jean Alesi – lovely guy, looked the part, tremendous guts, too emotional, drove with his heart…” Shortly before Jean’s death, indeed, he asked Jabby to become his manager: “I didn’t go to Avus – we were to have dinner in Paris the week after to discuss it, but he never came back…”

Behra stayed with Gordini for three years, but the cars rarely lasted, and his frustration mounted. There were, however, occasional successes, as in the 1954 Pau Grand Prix, where he defeated Maurice Trintignant’s factory Ferrari.

On Sportsview, a BBC programme of the time, a clip of the race was shown, and I was captivated by the battle between the dapper, fastidious Trintignant, and the stocky, charismatic Behra. Right there I was hooked, and a few months later, in the Oulton Park paddock, gazed endlessly at Jean’s light-blue Gordini. It had qualified second for the Gold Cup, but disappeared after a couple of laps.

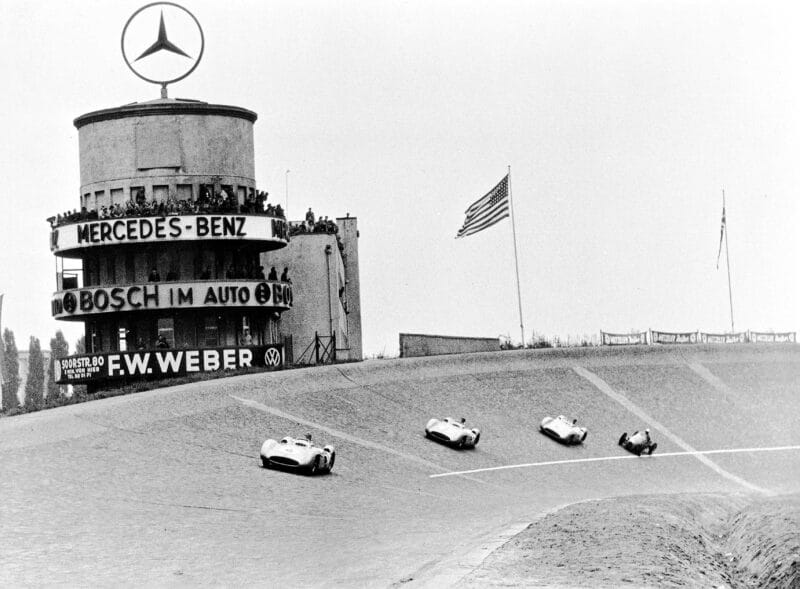

Soon after there was a non-championship race at Avus, put on as a showcase for Mercedes. Karl Kling was allowed to win at home, and the only happening of note was that Behra’s Gordini clung on to the three streamlined W196s, achieving speeds unthinkable without a tow.

Needless to say, the Gordini expired after 15 laps, but Denis Jenkinson was ever after inclined to cite Behra’s drive as the quintessential example of what he called ‘tiger’, this an indomitable refusal to give in.

Behra’s tiny Gordini hangs on to Mercedes streamliner trio at Avus in ’54

Daimler-Benz

For 1955 Behra moved to Maserati, but how different his career might have been had he stayed his hand on the contract a little longer, for Alfred Neubauer, needing support for Fangio, was looking around: “I thought of Behra – but he had already signed for the opposition…” Eventually, of course, he signed one S Moss.

As it was, Jean found at Maserati his spiritual home, and his three years there were to be the happiest of his racing life. Through another Mercedes summer the 250F was unable to trouble Fangio and Moss, but Behra was invariably ‘best of the rest’, and won non-championship Grands Prix at Pau and Bordeaux, as well as several sports car races.

At the end of the season, though, he crashed in the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod, suffering a broken arm and torn tendons in his right hand. As well as that, his right ear was severed, and this was to be his most celebrated injury. Thereafter he would wear a plastic ear, which he was wont to remove when the occasion demanded, as in a crowded restaurant. “There’s always a table available then,” he would grin. “Sometimes several…”

In the course of his career Behra did indeed have an enormous number of accidents, and this was long before the advent of proper helmets and fireproof overalls, let alone seat belts and rollover bars and gravel traps.

In 1949 he came off his Guzzi at Tarbes (broken arm and collarbone), and the following year at San Remo (broken kneecap); in ’52, while leading the Carrera Panamericana, his Gordini went off the road and into a ravine (seven broken ribs), and then he crashed at Sables d’Olonne (broken arm); in ’53 there was an accident at Pau (broken arm, displaced vertebra); in ’55 came the Dundrod accident, and in ’57 shunts during Mille Miglia testing (broken wrist) and at Caracas (serious burns to arms and face). The list went on.

‘Jean Behra’, wrote DSJ in September 1959, ‘had more guts than the majority of today’s drivers put together. He never knew the meaning of fear, and in consequence tended to drive over the limit more often than not. The way in which he would recover from injury and return straight away to racing was remarkable. A lot of people, drivers included, openly disliked Behra for no other reason than that they were secretly envious of such a tough little man, who would have the most almighty accident, climb out of the wreckage and come back for more.’

In the ’50s Jenks was frequently in Modena, where Behra was an almost permanent resident at the Albergo Reale. “What I liked most about Jean,” he said, “was his pure love of racing cars. He was a good mechanic, but he never worked on cars for the fun of it: what mattered was making them faster. They loved him at Maserati, because he was happy to ‘live above the shop’. There was no bullshit about Jean. He was a racer’s racer”.

Behra accepted Moss as number one at Maserati

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

At the end of 1955 Mercedes withdrew from racing and Fangio signed for Ferrari, while Moss joined Behra at Maserati. Plainly Stirling was the best driver in the team, the accepted number one, but Jean welcomed him, and had an untypically consistent season, finishing fourth in the World Championship, and again winning a number of sports car races, including the Nürburgring 1000Kms.

“Behra was one of the greatest fighters I ever came across,” says Moss. “If you passed Castellotti or Musso or Collins or Hawthorn, that was the end of it, but with Jean there was no way you could put him out of your mind – you had to keep your eye on your mirrors, boy!

“He was an incredibly tough competitor, you know, and that made him unpopular with some of the drivers, but I thought it was his greatest strength, and I very much identified with it. He was always fair, too – I mean, he wasn’t about to say ‘After you’, but he’d never do a Farina on you! I’d always feel quite happy going into a corner alongside him.

“Fangio, I believe, said Behra was ‘too brave’, but I’m not sure I’d say too brave – not in the way that Stuart Lewis-Evans was, for example. I always liked Jean: he was there to get on with what he was doing, and he did it bloody well…”

Behra shared victory with Fangio at Sebrig, ’57

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

For 1957 Moss left Maserati for Vanwall, but any hopes Behra may have had of regaining his number one status were dashed when it was announced that Fangio was coming aboard for what would be his last season.

Jean revered Juan Manuel, and in point of fact had the finest year of his career. The pair shared the winning Maserati 450S at Sebring, and in a similar car Behra won the Swedish GP, partnering Moss. Clutch failure kept him from winning the British GP, but there were F1 victories at Pau, Modena and Morocco, and a couple more – in a BRM, no less – at Caen and Silverstone.

Financial problems drove Maserati out at the end of 1957, whereupon Jean signed for BRM. But the following season was unsatisfactory, for the car, while sometimes quick, was lamentably unreliable and frequent brake failures – one of which pitched him into the Goodwood chicane wall – did nothing for his confidence.

What kept Behra going in 1958 was a new relationship with Porsche, for whom he was consistently brilliant in the little RSK sports cars, finishing second at the Targa Florio and third at Le Mans, as well as winning events as disparate as the Mont Ventoux hillclimb and the Berlin Grand Prix – at Avus.

By general consent Avus was a singularly stupid race track, comprising two flat-out autobahn blasts, with a hairpin at one end and the notorious steeply-banked curve at the other.

To Behra, though, a race was a race. When the USAC brigade came over in 1957 for the Trophy of Two Worlds at Monza, the Europeans had little enthusiasm for a banked track which Tony Bettenhausen’s Novi would lap at 177mph! Maserati, though, built up a special car, and Jean was mortified to find it too slow to compete with the Americans. I could always readily picture him in a roadster at Indianapolis.

Behra, at the Nürbirgring in 1958, found little success with BRM

Grand Prix Photo

Fundamentally, Behra had enjoyed the BRM team, if not sometimes its cars, and he would probably have stayed on in 1959 – had not there come a call from Maranello.

This was like coming home – Modena, the Reale, ceaseless testing – and the new association began well: in the Dino 246 Jean won the Aintree 200 from team-mate Tony Brooks.

“I rated Behra very highly as a driver,” says Brooks. “In a decent car he could give anyone a run for their money. Mind you, although we were team-mates I didn’t know Jean that well – he didn’t speak English, and I didn’t speak French. ‘Ciao’ and ‘bonjour’ was about as far as we got!