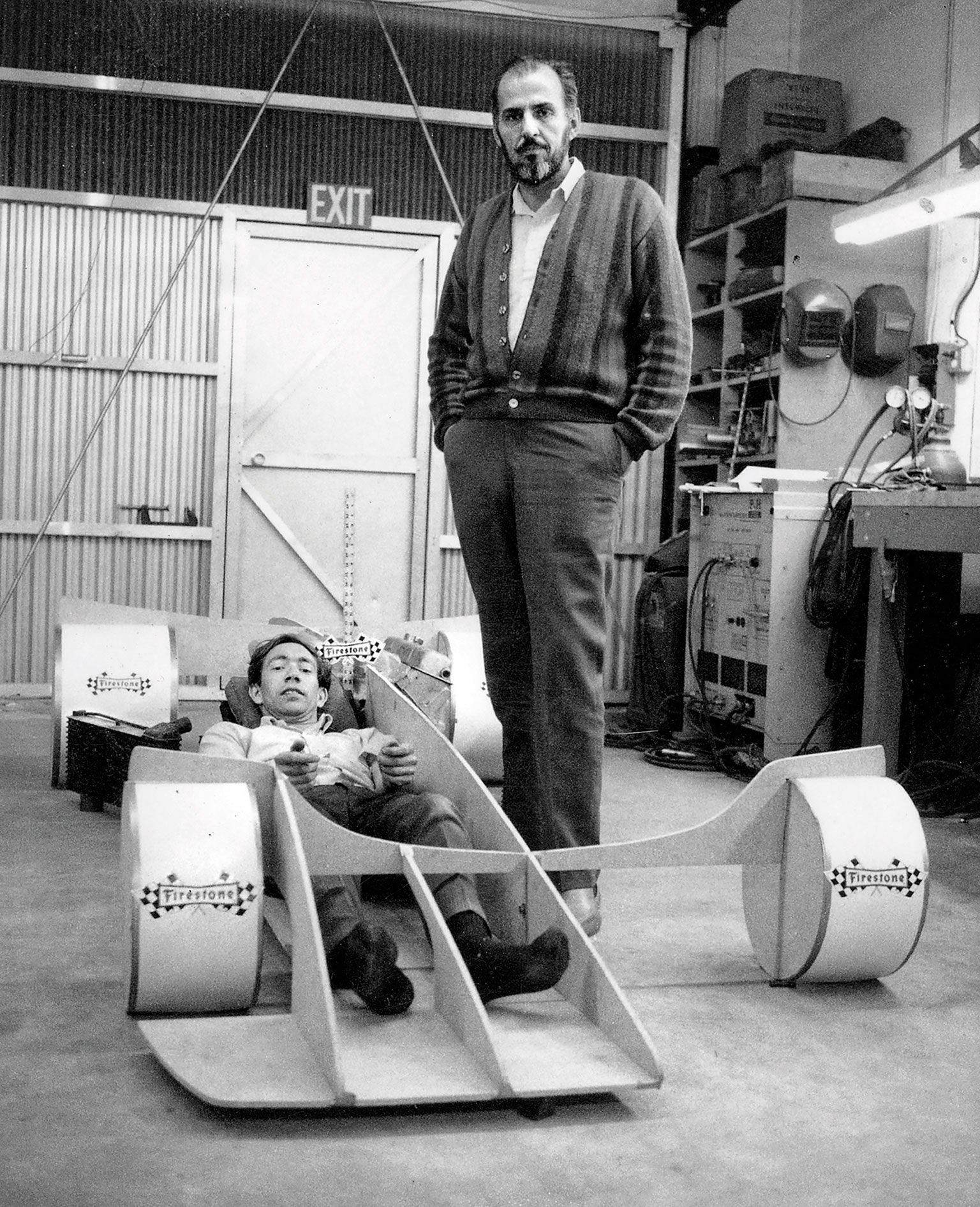

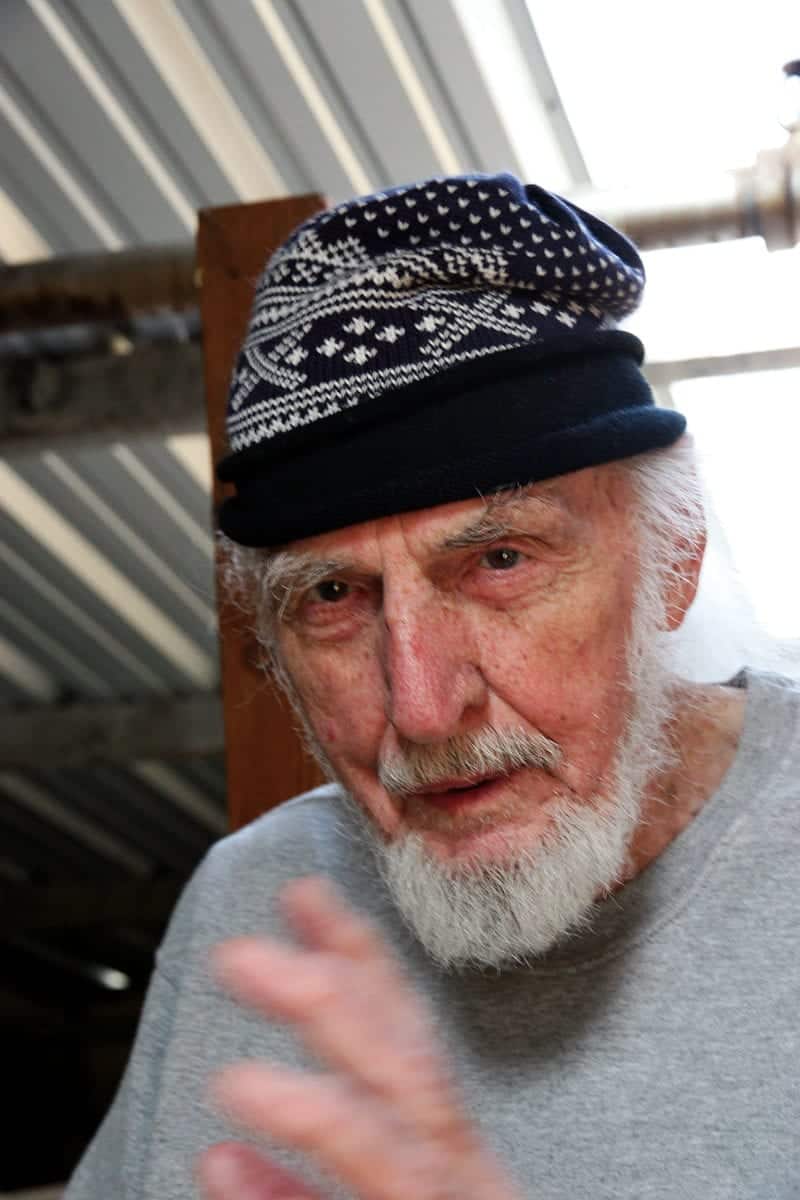

We would meet of a misty morning at his stored old racer’s warehouse, a graceless steel shed in an unlovely part of plebeian Salinas, over the hill from patrician Monterey, California. The cavernous interior was stuffed three tiers high with treasures: complete racecars or monocoques, body sections, suspension and running gear parts, engines and transmissions or their elements, racks of new metal stock and boxes of old junk, design drawings, pictures, banners, trophies, filing cabinets… thousands of keepsakes of bygone times. The Wizard’s Cave, I called the magical space.

The old Wizard was lean enough — he denied himself midday meals — to claim proudly that he could still wear his old Army Captain’s dress uniform. He would sit with us for hours in his shabby office, his lanky frame bent into a rickety old swivel chair, knitted stocking cap and upturned jacket collar defying the chill of his unheated space, answering our questions or trying to. Oft-times the memories came hard, sometimes not at all.

But then there would be a sudden spark and he would leap up and dash out across the shop floor to find something he had thought to show us. He knew just where it was and, much spryer than I, the 88-year-old would clamber like a young gymnast up and up through precarious levels of rough timber flooring. He gave me to think that he had erected this scaffold-like structure with his own hands 20 years before.

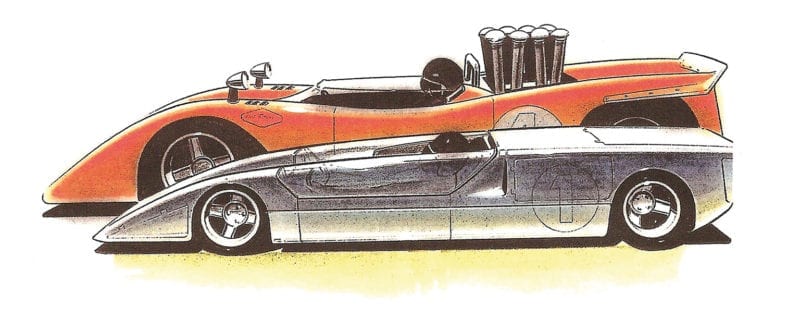

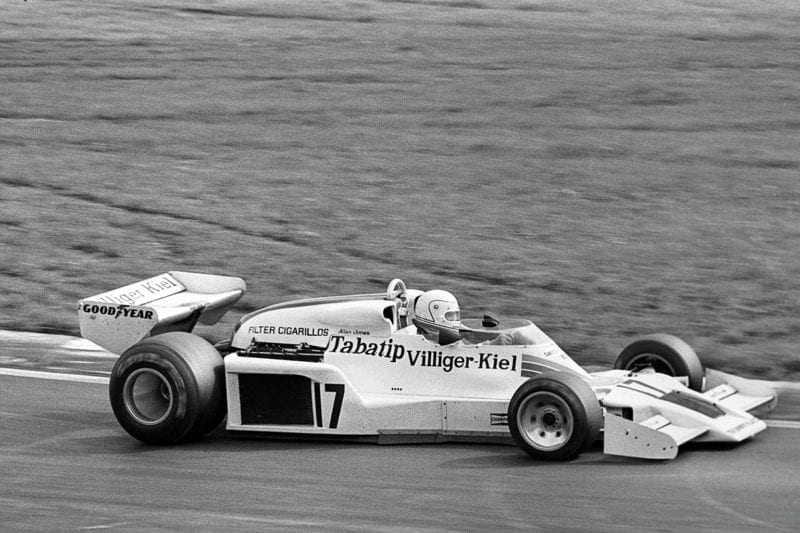

Packed storage unit housing Shadow memories. Below: Vic Elford drove bizarre MkI Can-Am in 1970

In motor sports history, Shadow is not ranked among the premier teams. It did win races, but never regularly; its cars were often fast, but too often fragile; the one drivers’ championship, by Jackie Oliver in the Can-Am of 1974, was a worthy achievement by a well-run team, but unfortunately came against thin opposition at the tag end of a dying series.

Asked about his fondest memory from the Shadow days, Nichols paused to consider it. The pause grew long. Finally his agelessly acute eyes refocused and he said slowly, “Maybe winning the Race of Champions with Tom [Pryce], the first F1 win for Shadow.”

Ah, yes. That was at Brands Hatch in March of 1975. Despite the event’s name this early-season sprint for F1 cars, together with a few F5000s, was not a grand prix, not part of the world championship, so not all GP teams and drivers participated. But the grid did host the likes of Donohue, Fittipaldi, Ickx, Jarier, Peterson, Scheckter and Watson. Beside Shadow’s team of two, there were full-on works entries from McLaren, BRM, Ensign, Lotus, Penske, Surtees, Tyrrell and Williams. Young Shadowman Tom Pryce out-qualified them all. Then he beat them all.

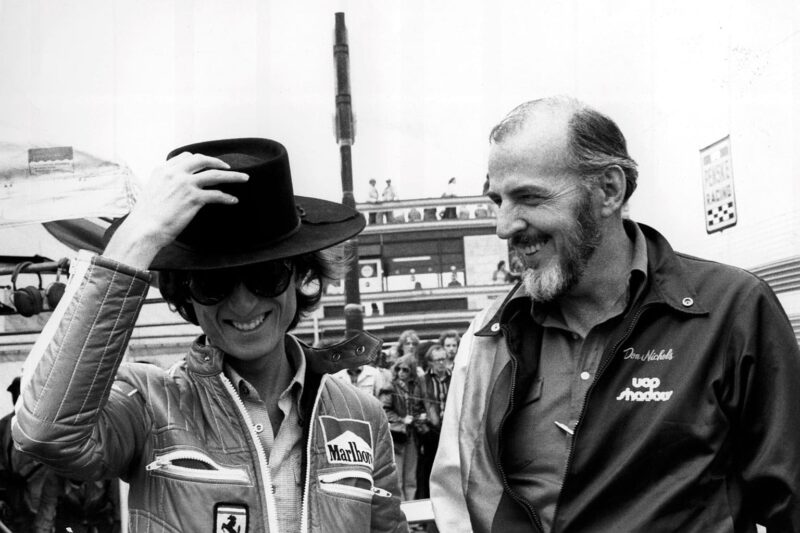

Nichols prided himself on doing things differently. He shares his iconic black cowboy hat with Ferrari chief Luca di Montezemolo on the grid in Canada, 1974

Getty

It was still early in the American team’s third season of international F1 racing, a season that started with exciting promise. Shadow’s new DN5, its third single-seater model, showed immediate speed. In January, lead driver Jean-Pierre Jarier qualified fastest for both the two opening grands prix, Argentina and Brazil. They were Shadow’s first pole positions in Formula 1.

Shadow: the Magnificent Machines of a Man of Mystery

Shadow: the Magnificent Machines of a Man of Mystery