This was a surprise – and if push came to shove would he really have gone on strike? – which reminded older members of the MotoGP travelling circus of their trip to Brazil in 1992, for the penultimate round of that year’s 500cc world championship, starring Mick Doohan and Wayne Rainey.

Funnily enough, this was Dorna’s first season working in GPs, owning only the TV rights, not the championship itself.

The 1992 Brazilian grand prix was staged at the Interlagos Formula 1 circuit which featured a sixth-gear kink on the start/finish, lined by a concrete wall. Zero runoff. When riders arrived they couldn’t believe what they saw.

“How are we supposed to race here,” they asked. “It’s impossible!”

So how did they even come to be there, especially since Rainey had recently established a riders’ union, the International Motorcycle Racers Association, intended to protect the rights and lives of riders?

The previous year IMRA had sent Kevin Schwantz to Interlagos, where he inspected the track and had to tell angry locals that it wasn’t good enough, so there would be no 1991 Brazilian motorcycle GP.

Another attempt was made to okay the track in the summer of 1992. An FIM rep was despatched to São Paulo, in the company of IRTA boss Paul Butler and recently retired rider turned IMRA riders’ rep Didier de Radigues.

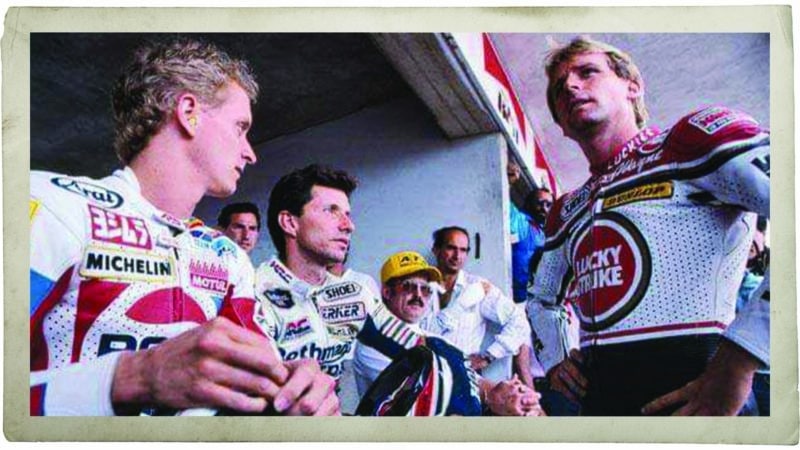

A riders’ meeting at Assen 1990: Doohan, Chili, Stuart Shenton, Masahiro Shimizu, Mackenzie, Rainey, Sarron, de Radigues and Gardner

Mat Oxley

Somehow – no one knows how – they gave the track the all-clear. Therefore the riders had nowhere to go – the IMRA rep had said yes, so how could they say no?

The debate reached a riotous conclusion on Friday evening in Dorna’s office above pitlane.

Some riders wanted to ride, others didn’t. Rainey said they had to race, because their own representative had said they should.

But… Rainey was second in the 500cc world championship, rapidly catching points leader Doohan, who hadn’t raced since Assen, where he had broken a leg. Of course Rainey wanted to ride and many others agreed, unless the weather turned bad.

Doohan stayed out of the argument, but Rainey’s former team-mate Eddie Lawson didn’t. Quite the opposite. The four-time 500cc king was convinced Rainey only wanted to ride to win the title, never mind the safety of his fellow riders.

Lawson walked angrily out of the meeting, promising, “Whatever you guys do, I’ll do the opposite”.

And he was true to his word. Saturday morning dawned dark, miserable and wet. When pit lane opened for FP3 there wasn’t a sound, until one 500 was bumped into life and warmed-up: Lawson’s Cagiva C592.

Lawson climbed aboard, rode down pit lane and stopped outside the Marlboro Team Roberts garage, where Rainey was sat with his crew. Lawson revved his engine – ringa-ding-ding-ding – to make his point and took off for practice.

If there was a strike it wouldn’t be complete. And if Doohan was thinking of riding then Rainey would have to ride too. So there was no strike.

Three years earlier Lawson and Rainey had been on the same side, when they played a leading role in GP racing’s last successful strike.

The 1989 Italian GP was staged at Misano, where the top riders found the surface dangerously slippery in the rain. They told the organisers that they wouldn’t race if it rained on Sunday. A few laps into the 500 race the rain arrived and everyone rode into the pits, led by race-leader Schwantz.

Workers painting the grid at Nogaro during practice for the 1982 French GP, where the riders went on strike

Mat Oxley

Mayhem ensued, for at least an hour. All the riders huddled together in Randy Mamola’s motorhome, hoping to maintain a united front. And against the odds they did. All the top riders – Rainey, Lawson, Doohan, Schwantz, Wayne Gardner, Christian Sarron, Kevin Magee, Niall Mackenzie, Ron Haslam and Rob McElnea – refused to ride.

But the promoters refused to cancel the race. And they got a race. Of sorts. Local Honda NSR500 rider Pierfrancesco Chili was told by his team that he must ride and he won the race, far ahead of a bunch of skint privateers, riding ancient Honda RS500s and Suzuki RG500s. Chili wept on the podium because he knew he was now the ‘scab’ of the paddock.

The race was something of a comedy act. I was stood in pit lane, where Rainey, Lawson, Schwantz and a few other strikers had gathered to hurl abuse at the strike-breakers. Each time Chili rode past he was met by a tirade of cussing and swearing. In fact there was something of a party atmosphere in pit lane – the strikers were delighted that they’d stood their ground and given the middle finger to the race promoters and the FIM.

Of course what happened at Misano that year was the exact opposite of what happened at the 2018 British GP, when rainfall during practice caused a pile-up at the end of Hangar Straight, which effectively ended Tito Rabat’s MotoGP career.

When the rain returned on race day, Dorna management asked the riders what should happen and the majority said they didn’t want to race due to circuit conditions, so there was no race. This has been Dorna’s mantra ever since Interlagos 1992 – the riders only race where they want to race. After all, they’re the only people risking their lives.

The last strike before Misano 1989 was the French GP at Nogaro in 1982 when the promoters had so little concern for safety and the wellbeing of riders and teams that it was shocking. Pre-practice was staged on Thursday while workmen were still painting the grid!

On Sunday morning I watched angry fans break down the circuit fences to gain entry, because they’d heard that ‘King’ Kenny Roberts, Barry Sheene and the other top riders had already gone home. No way were they going to pay to watch a few privateers ride around for their best pay day of the year.

Silverstone 2018: Xavier Simeon, Jorge Lorenzo, Marc Marquez and Cal Crutchlow leave the IRTA office after deciding to cancel the race due to poor circuit conditions

Honda

The race was won by Swiss rider Michel Frutschi, who was killed during practice for the following year’s French GP at Le Mans, when he fell and hit a catch-fencing post, another tragedy in the march to safer circuits.

COTA was a reminder that the fight for better circuits never ends. Thus the issue of rider safety will never go away, which is why there’s some talk about re-establishing a riders’ union that has enough clout to withhold their labour when working conditions are unacceptable.

But would a riders’ union work now?