Then it was the brakes which were poor by any standards of that era, and frankly alarming given the level of performance on hand. The pedal felt dead, the retardation limited, the propensity to lock up considerable. But once you knew, the problem could be managed. By contrast, the gears required constant thought if disaster were to be averted.

It sounds so easy: it’s a five-speed transmission, with a slick and easy change, with first, third and fifth exactly where you’d expect to find them in almost any similarly specified road car. Great. Except that second is not below first, it’s below third, where you’d expect to find fourth which has itself migrated one plane to the right where it lived directly below fifth. So if you pull back from third to get fourth as you might in any other five speed car, you get second and blow the engine to pieces. Or, you could change down from fifth into what you think is fourth and also find second, blowing it to smithereens.

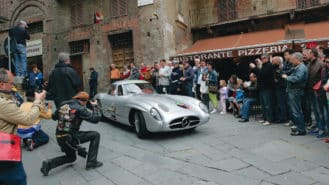

I always pondered its value, particularly after Simon Kidston told me he thought it one of the two most valuable cars in the world, the other being another 300SLR, the roadster in which Stirling Moss won the 1955 Mille Miglia. Could it really be so? The brace of Uhlenhaut coupes are wonderful and beautiful cars, but neither turned so much as a wheel in competitive anger.

And I always thought that was necessary. For a car to command the toppest of top dollars, I thought it needed to be beautiful, rare, fast, wonderful to drive, potentially usable in modern events, from the right brand, historically significant and successful in competition. The Uhlenhaut coupes ticked every box save the last.