MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

As with its first win, so with its 114th: Pastor Maldonado’s surprise ending of Williams’ long drought elicited the same reaction as Clay Regazzoni’s surprise opening of the floodgates all those 33 years ago at Silverstone – a universal and heartfelt “Bravo, Frank!”

The company with Engineering tellingly etched in its name is popular in pit and paddock and with the public. The story of Sir Frank’s indefatigability in the face of, first a lack of finance, then a negative perception – the campervan, the wheeler dealer tag, Walter Wolf’s brush-off – and finally physical disability is as sensational as he was typically understated in Barcelona last week. Truly, he has seen all sides of life, not just of Formula 1.

Maldonado’s success in Spain is a contender for Williams’ most memorable victory, coming as it did in the aftermath of a disastrous 2011: the least memorable season in its history. But with 113 others, – third, after Ferrari and McLaren – to choose from, plenty vie for the honour.

1979 British Grand Prix – Clay Regazzoni

FW07 was the ‘Lotus 80’ that Colin Chapman should have built: sturdy and (as) sensible (as any ground effect car could be) while remaining sleekly efficient. Fundamentally white, it possessed an All Blacks aura. Designer Patrick Head was its fearsome flanker, digging out the speed and making it available to one of the few F1 drivers capable of taking up the crash ball. Alan Jones was superb at Silverstone – he possessed good hands as well as a bull’s neck, strength and attitude. On pole by six-tenths, he was leading by a wide margin when his new DFV vented on lap 40.

Many had deemed the signing of Regazzoni an error. The tough-minded Ticinese, however, now proved to be the safe pair of hands that Frank had hoped for: Jones would win the next three Grands Prix – but it was ‘Regga’ who won Williams’ first.

1983 Monaco Grand Prix – Keke Rosberg

The Finn stood no chance of successfully defending his world title such was the widening power gap between his atmo and the turbos, but not once did he flinch from the fight. His flamboyance in qualifying, in dry and wet sessions, put him in the position – fifth – where his tyre gamble should be deemed calculated rather than merely hopeful. Slicks put him ‘on pole’ when the expected rain didn’t fall, and he skirted walls, kerbs and patches of damp to win. His every lap was bewitching.

What made his performance unquestionably great, however, was his opening salvo when the track was wettest. He could have played a waiting game, with one eye on the sky. Instead, a bullet start, followed by a slicing pass on Renault’s Alain Prost, meant that his FW08C was leading before the completion of the second lap.

1984 Dallas Grand Prix – Keke Rosberg

Even this most ardent advocate and proponent of opposite-lock was resigned to an understeering future aboard the FW09, a conservative design playing second fiddle to ironing the bugs, of which there were many, from Honda’s new V6 turbo. The latter’s Himalayan power curve ought to have made this concrete-lined, slow-corner track that was fast crumbling an insurmountable summit. Jacques Laffite qualified his FW09 24th and did well to finish fourth, albeit two laps behind the winner – who just happened to be his team-mate.

Rosberg had qualified eighth, almost five seconds faster than unhappy Jacques, and drove with an élan and accuracy that nobody could match on the lung-burningly hot day that François Hesnault, Eddie Cheever, Stefan Bellof, Derek Warwick, Riccardo Patrese, Andrea de Cesaris, Johnny Cecotto, Patrick Tambay, Nelson Piquet, Mark Surer, Michele Alboreto and even Niki Lauda and Alain Prost crashed.

1987 British Grand Prix – Nigel Mansell

The most outrageous dummy since Pelé ‘sold’ the Uruguayan ’keeper at the 1970 World Cup. An overtake, or at least an attempt, was undoubtedly coming such was Mansell’s grip advantage and ferocity of focus, but this being ‘Our Nige’ in front of his hepped-up fans at Silverstone, it was bound to be spectacular to the point of showbiz: a 190mph feint left, then a lunge right into Stowe. Nelson Piquet, the team’s other driver, though hardly a mate, saw it late and moved to block before wisely acceding – without good grace.

The FW11Bs had dominated throughout the weekend, Piquet stealing Mansell’s pole thunder and leading for 62 of 65 laps. Their initial plan was to run non-stop, but an imbalance forced Mansell to fit new rubber at mid-distance. Ignoring his fuel readout’s red warning, this blue-collar cavalier then hunted Piquet down, and the kill, when it came, was merciless.

1994 Japanese Grand Prix – Damon Hill

Benetton’s nimbler car and strategies had given Michael Schumacher an edge that he did not in truth require in the void left by Ayrton Senna. Hill, despite impressing as the conduit of a distraught team’s efforts, was by now searching his soul: was he really the man, the driver, to take on Schumacher? Having chased shadows all season, he turned the tables at storm-hit Suzuka.

Runaway Schumacher held a seven-second lead when the race was halted after 13 laps because of a deluge. Soon after the restart, however, it became clear that he and Hill were on different strategies: a two- and one-stopper respectively. Both suffered enforced compromises: Schumacher’s was the extra 10 litres of fuel at his first stop in case the race finished, as had been indicated, 10 laps early behind the Safety Car; Hill’s was a stuck rear that meant he was sent out on just three new boots. The Englishman adapted and was the faster, moving into the lead on aggregate as well as on the road. After a Schumacher splash ’n’ dash, however, it was the same old story: the German closing relentlessly on another win – until Hill conjured a second on the last lap to win by 3.4.

When Schumacher reached into the FW16B to respectfully congratulate his rival, he grabbed the hand of a man who knew that he had earned that respect and that their rules of engagement had been redrawn. These were annulled one week later in Adelaide.

1996 Portuguese Grand Prix – Jacques Villeneuve

Father Gilles was an impulsive genius whereas Jacques was a compulsive theoriser who mulled over every possible eventuality. This was difficult in his rookie year on tracks he did not know. Estoril, however, was the exception, thanks to 3000km of testing. He disarmed his race engineer by informing him that an outside pass was possible at the long final right-hander and that he wanted his FW18 set up accordingly.

A tardy start saw him slip to fourth behind team-mate Hill, the Benetton of Jean Alesi and Michael Schumacher’s Ferrari. It stayed that way until lap 16, whereupon Jacques, as mooted, swept around Schuey. Michael’s entry speed had been compromised by a backmarker – but even so. A clean pass of Schumacher was something that Damon had never managed. Hence his being released.

Villeneuve’s victory – Hill was hampered by late-race clutch problems – and more significantly that move signalled that the Canadian was indubitably ready to win a world championship, if not this season’s then the next’s.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

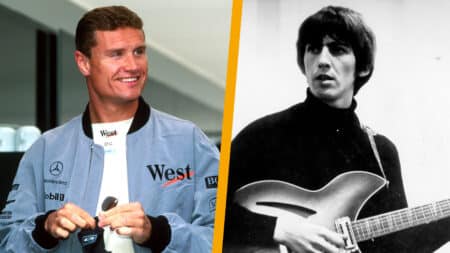

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song