The Renault tragedy in 'race of death' that changed motor sport forever

The death and injury toll in the 1903 Paris-Madrid event was so severe that it was stopped early, and brought about a road racing ban in France and Spain. Among the grim list of casualties was Marcel Renault: one of the co-founders of the car-making empire

Louis Renault is told of his brother's crash, as the 1903 Paris-Madrid race is ended early

Roger Viollet/Getty Images

It’s timely to take a look at just how it all started for Renault, which pre-dates even Mercedes as a racing entity, formed at the very dawn of motor racing. The sport in turn was a crucial part in establishing Renault as a major manufacturer.

There are photographs from the finish line of the ill-fated 1903 Paris-Madrid race, halted at Bordeaux by the French government after an appalling series of death and injury along the way, that show the recoil of horror upon Louis Renault as he is told the devastating news: his brother Marcel has been gravely injured along the way.

Suddenly Louis’ stirring second place standing overall – his Light-class, self-built machine ahead of all but one of the full-size racers – meant next to nothing. It’s doubtful that he would have continued even had the French government not intervened and stopped the race there and then, at Bordeaux rather than the original destination of Madrid, alarmed at the human carnage in the race’s wake, Marcel just one of many casualties. The disgraced racing cars were towed behind horses to the train station and sent back to Paris whence they came.

That, it seemed, was that; an end to this recent folly of racing automobiles across the country, just eight years after the sport had been invented, during which time the technology and speed of the cars had advanced at breakneck speed. Whereas the first contest had been won by Emile Levassor’s Panhard-Levassor at an average of just 14mph, Fernand Gabriel had, over the 630 miles from Paris to Bordeaux, averaged 65.9mph in his Mors, skimming disaster between other competitors and up-close bystanders as he braved the dust clouds from his starting position of 82nd. Among the 10 fatalities were four members of the public. It was an inevitable carnage with the fastest cars exceeding 90mph in the dust, crowds that were totally unfamiliar with speed who bordered and sometimes stepped onto, the roads, the better to see these supermen in action. Then there was the very real hazard of wandering dogs. It had to be stopped.

Marcel Renault at the start of the 1903 Paris-Madrid race

Getty Images

But it wasn’t the end of motor racing. The economic power and resultant political clout of the car manufacturers saw to that. Louis Renault’s company was at the forefront of a national industry that would produce 30,000 cars in 1903 — around half the total world production — employing 25,000 people, with the promise of vastly more to come. Already it was very obvious that the new-fangled machine was going to contribute in a major way to France’s economy and help turn it into an industrial powerhouse.

Louis Renault was an unlikely racing hero, the more so to later generations who came to associate the name with the infamous boorish right-wing industrialist – who had an entire village moved at his expense so as not to impinge upon his vast estate, the access to which was through an underground tunnel, or the wronged ‘collaborator’ who died in suspicious circumstances whilst imprisoned shortly after the liberation of France in 1944. Born to a wealthy industrial family of button makers, he was a highly unconventional personality, with no social graces, who struggled at school and often played truant. His solace came in the tool shed of the family house in Billancourt where he would experiment with all things mechanical.

As a 21-year-old in 1898, he was still in that shed even as his elder brothers Fernand and Marcel were working conscientiously in the family business. In there, he devised an ingenious gearbox for a de Dion tricyle that he’d converted into a quadricycle. In place of the traditional belts and chains, he made a uj-jointed gearbox, with three speeds and a reverse, whereby the third speed was direct drive. It was such an improvement over the standard car that he received orders for a dozen more and at this point he was persuaded by his brothers to set up manufacture in his own right rather than sell the gearbox patent to an existing manufacturer. Fernand and Marcel invested in and helped set up the business, in which all three would be shareholders upon its establishment in February 1899.

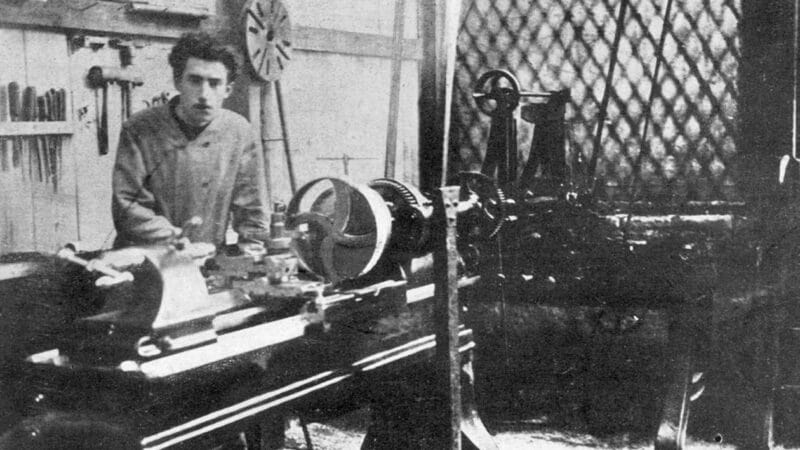

Louis Renault works on his De Dion in the family shed

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Renault factory in 1903

Corbis via Getty Images

As a way of proving the speed and durability of their cars, Louis and Marcel entered them in the early city-to-city races. The cars were agile and quick and the brothers, Marcel in particular, were formidable drivers. The little Renault took giant-killing results. The classes were divided according to car weights (which effectively limited the size and power of the engine) and the Renault ‘Light Cars’ were frequently quicker than all but the best of the cars from the Heavy class. Marcel took a brilliant victory in the 1902 Paris-Vienna, his 3.8-litre Renault Type K out-performing the 9-litre Mors and 13-litre Panhards over roads little more than farm tracks in many places.

After Marcel had tested his more powerful 6.3-litre Type O in preparation for what was set to be the most formidable contest of all, the 1903 Paris-Madrid, he commented, “God, but it’s fast.” It was capable of almost 100mph (well in excess of the official land speed record). The cars started at intervals and were timed to the next control point, essentially the equivalent to today’s rallying special stages. Louis soon led the light car class and rose to second overall. Marcel in the sister car, started much further back, in 60th place, and therefore had more delay passing slower cars but by the Poitiers control point was almost with the leaders. He crashed a few kilometres past the town of Couhé-Vérac, getting into a ditch and being thrown out while dicing with Leon Théry’s Decauville. In the dust cloud of Théry he missed a left-hand turn. He was thrown against a tree and knocked unconscious. He never regained consciousness. He would die from his injuries two days later, adding to the race’s grim toll.

A devastated Louis Renault would never race again but go onto to become one of the world’s greatest industrialists. The economic power of the new motor industry ensured it enough political clout to keep the sport alive, but never again would the races be contested from city to city. The way forward had already been demonstrated the previous year, with the Belgian Circuit des Ardennes race, six laps around a 52-mile circuit of closed public roads.

Renault the company re-entered racing and Louis’ old riding mechanic Ferenc Szisz took his Renault AK victory in the very first Grand Prix, at Le Mans 1906. Turbocharging, pneumatic valves, exhaust blowing (all Renault innovations) and multiple world titles lay a long way into Renault’s future. Those things are now part of its glorious past as the next chapter is still unfolding.