MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Races had always been against the clock.

Practice was a more leisurely pursuit: a chance to (re)acquaint and rehearse and, hopefully, to fine-tune and, at worst, rebuild.

Until the Monaco Grand Prix of April 1933, that is.

Where better to emphasise the inherent advantage of places on the front row and to begin awarding them rightfully to the most deserving – that is to say fastest – drivers?

They had been doing it at the Indianapolis 500 since 1915 – over one lap initially, then four (from 1920), then 10 (from 1933), and then back to four (from 1939) – but this was the first occasion that a grid for a major European race was arranged according to lap times set during its practice sessions: fastest first.

In a snowy February, the inaugural Pau GP – Monaco’s dowdy cousin – had recorded lap times during practice but reverted to the industry-standard ballot method to finalise its starting order. Naturalised Algerian Marcel Lehoux, fastest in practice, thus sat on the penultimate row. He won nevertheless, defeating his more venerated compatriot Guy Moll in a sister Bugatti Type 51.

Practice in Monaco, however, was for keeps.

And this keener edge soon claimed its first casualty.

Rudolf Caracciola was the most calculating of drivers. On this occasion, however, he appeared unusually hasty. In his book A Racing Driver’s World he insisted that he was merely showing new team-mate Louis Chiron the Alfa Romeo ropes.

For 25 laps on Thursday morning – the first of three dawn hour sessions before the race on Sunday – their 8C Monzas ran in close formation at increasing speed. Their urgent progress was noted, as was the ease with which local hero Chiron, a long-time Bugattiste, adapted to the car and kept pace with an established marque ace.

‘Caratsch’ wistfully noted his friend’s astonishing talent.

The guided element of the tour got lost en route. It became a pissing contest basically.

Caracciola had just shaken off his shadow when it happened. A front wheel locked under braking for Tabac and the white Alfa with a blue stripe struck the stone balustrade on the outside.

Tazio Nuvolari also crashed his ‘Monza’ here – even the greats appeared unsettled that day – but escaped unharmed. Not so his Alfa Corse colleague of 1932.

A shocked Caracciola leaped from the wreckage and crumpled upon landing. His right femur and tibia had suffered compound fractures and he had to be carried on a chair to the tobacconists set underneath the nearby baroque steps.

His best time – matched, of course, by Chiron – would have placed him on the three-car front row.

Achille Varzi, calmness personified in his works Bugatti T51, was on pole position by a second – a time set on a drying track during Saturday’s session. Fittingly he went on to win the race after a Homeric duel with Nuvolari.

Timed qualifying was here to stay.

But it was not immediately adopted universally. Only certain French races, encouraged by influential journalist/administrator Charles Faroux, used the system in 1933.

The Marne GP at Reims in July timed practice to within a tenth – and that man Lehoux was again on pole.

Nuvolari, by then at the wheel of a monoposto Maserati 8CM, took the practice honours at Nice in August (below) – though Philippe Etancelin, the Frenchman with the trademark back-to-front cap, equalled him in his Alfa Romeo 8C.

Nuvolari was also on pole at Miramas for the Marseilles GP three weeks later.

In between times Jean-Pierre Wimille’s 8C occupied prime position at the Comminges GP – albeit by only a second over a 4min 30sec lap.

The first three rows at Monaco – from Varzi to Lehoux – had been covered by five seconds.

The idea spread south in 1934 to Casablanca, where Lehoux seized pole in a Scuderia Ferrari-run Alfa Romeo Tipo B single-seater.

It also spread east to Switzerland, the home of precision and accuracy – albeit tentatively. Only pole position for the national GP was decided by time. The rest of the grid at Bremgarten – lined up behind Hans Stuck’s Auto Union – was sequenced by ballot.

Count Felice Trossi, Lehoux (twice), Varzi, Chiron and Nuvolari all topped the time sheets during the season, but they were topped by Etancelin, whose Maserati 8CM started from four pole positions: at Montreux, Vichy (a heat), Dieppe (another heat) and Comminges Grands Prix from P1.

Italy, Germany and Great Britain joined the fray in 1935, via the Coppa Citta di Bergamo, Avusrennen and Donington Park Grand Prix.

Nuvolari (thrice), a recovered Caracciola, Varzi (also thrice), Stuck, Manfred von Brauchitsch, Robert Benoist, René Dreyfus (twice), Lehoux – that guy deserves more credit than he receives – Chiron and Raymond Sommer grabbed poles as Germany’s ‘Silver Arrows’ carved up the big races and the fading forces of Alfa Romeo and Bugatti scrapped for the scraps elsewhere.

Auto Union’s Bernd Rosemeyer – the Senna of his age – was the one-lap wonder of the next two seasons, and his pole position for the 1937 German GP at the Nürburgring was perhaps the original masterpiece of an art not yet fully formed.

He was equalled in 1937, however: by Caracciola in the superior Mercedes-Benz W125.

Rudi’s four pole positions that season included one at New York’s Roosevelt Raceway for July’s Vanderbilt Cup. Its 10-lap format mirrored that of the Indy 500 and played to Rudi’s strengths. His deft tyre management saw him complete the 33 miles in 22 seconds fewer than the flamboyant Rosemeyer.

The latter practice sessions were timed to within a hundredth. The sport’s technology race was gathering pace on all fronts, and as the margins of its most important parameter narrowed, so too did the foci of the teams and their drivers.

With war looming, however, and the Silver Arrows continuing their domination from the 750kg Formula through to the new 3-litre supercharged/4.5-litre unblown regs of 1938, there were fewer poles to be won.

There were fewer yet in 1939.

The one-lap battle at the tail end of 1930s distilled to an internecine battle at M-B between Hermann Lang and von Brauchitsch. The latter, smoke hazing off his rear tyres, looked the faster, but usually it was the more mechanically sympathetic former who stopped the watches the sooner.

The most famous pole position of the era, however, came from an unexpected source.

There may have been a local slant to the awarding of pole at Pau in April 1938 to Dreyfus, but there can be no doubt that his torquey 4.5-litre V12 Delahaye, little more than a stripped sports-racer, was a match in speed for the new Mercedes-Benz W154s at this twisting street circuit.

Caracciola, still capable of winning but increasingly shy of that final qualifying tenth, joined Dreyfus on the front row. Meanwhile, Lang crashed and his entry was withdrawn. His fastest lap at the time was a second slower than the ultimate best.

Dreyfus’s stunning race victory in Pau was what mattered most, of course, but the scene and its tone had been set during practice.

Fractions matter – invigorate and unsettle – when they are posted for everybody to see.

And it’s been like that for, ooh, coming up to 2,524,608,000 seconds now.

Ever since Caracciola hit that wall.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

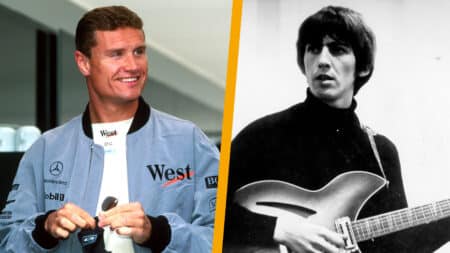

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song