Michal Kobierecki, assistant professor in the Department of Political Theory and Political Thought at the University of Lodz in Poland, has studied how major sporting effects can shape a country’s image. He says that sportswashing can fail when the world’s attention focuses on troubling issues.

“Organisers want to be at the centre of attention but that means that they will also be the centre of attention for human rights activists, for example. Hosting an event is an opportunity for those actors to put those inconvenient issues into the daylight, and hosts can suffer from what’s termed soft disempowerment.”

However, the rising number of international events being hosted in the Saudi Arabia — including Formula E and Extreme E races, the Dakar Rally, and a long-term F1 contract — are likely to see attention move elsewhere.

“States have long used sport as a means through which to alter things, and one of which is their external image,” says Grix. “In my experience, this process is rarely successful. If a state suffers from a poor reputation – say for human rights abuses – a few high-profile sports events are unlikely to change this perception.

“One way of looking at sportswashing is to see how these events can be normalised. Look at China: it hosted the Olympics but now has a big sporting event almost every week — including a grand prix. It doesn’t make the headlines any more, and it soon becomes the norm.”

Saudi GP is part of the Kingdom’s plans to change its image

Mario Renzi /F1 via Getty Images

Grix points out that countries have been using sport to bolster their images for decades; from Berlin’s pre-war Olympics, to the post-war Tokyo Games that helped rehabilitate Japan on to the international stage. Britain, which has a legion of critics as a result of recent wars, arms sales and punchy diplomacy, pitched itself as modern and inclusive at the 2012 Games.

There’s a complex question over where sport should draw the line, but few doubt that Saudi Arabia is beyond it, placed 151st out of 162 countries in the most recent Human Freedom Index published by the American libertarian Cato Institute.

Even so, F1’s current human rights policy allows grand prix racing to bypass the issue entirely by disregarding the policies of host countries, as long as they don’t apply to the races themselves.

“We focus our efforts in relation to those areas which are within our own direct influence,” it states. The policy also commits to assessing “any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which we may be involved either through our own activities or as a result of our business relationships”.

When asked if this assessment included sportswashing, F1 pointed to Domenicali’s comments on how races can focus attention on human rights issues.

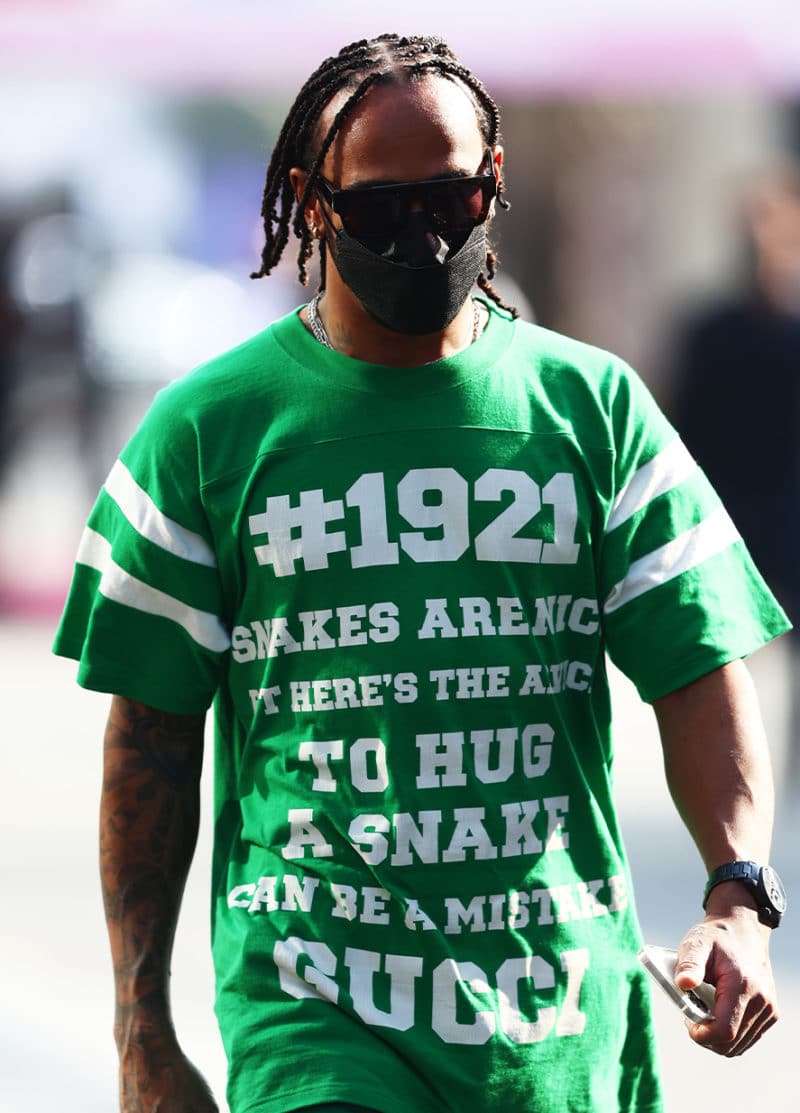

Hamilton wore a rainbow helmet in Saudi Arabia for last year’s inaugural race

F1 via Getty Images

Pierre de Coubertin’s vision for the Olympics was that sport would bring people together to discover that we have more in common than which divides us — in a modern sense, regardless of nationality, skin colour, religion, political persuasion or sexuality.

On that basis, F1 may have a case for racing anywhere. But it’s a multi-billion dollar industry, where plans are announced in quarterly investor meetings; teams are increasingly owned by multinationals or private equity investors rather than enthusiasts; and venues are chosen on the basis of profitability.

Saudi Arabia has made it clear that its motivation for hosting the race is to reform its appalling image, with officials speaking of “changing perceptions” and “reaching new audiences”.

But with such a weak track record of international sporting events being a force for change, you may find it difficult to see beyond one conclusion: that F1’s expansion to Jeddah is little more than a marketing opportunity to a regime that’s less enthused about the racing than it is with papering over a grotesque reality for subjects who are offered no voice.