Practice was very wet but qualifying bone-dry, favouring the three fastest Goodyear runners, Nelson Piquet (Brabham), who took the pole, followed by Carlos Reutemann (Williams) second, and Alan Jones (also Williams) third. But on race day the heavens opened again, favouring the teams contracted to Michelin, whose rain tyres were impressively grippier than the Goodyear wets. It was not therefore surprising that two seasoned and doughty hands who had decent cars underneath them, fitted with Michelins, did rather well. Jacques Laffite (Ligier) and John Watson (McLaren) had qualified alongside each other on the fifth row, but when a ton of lashing rain came down on race day they both drove superbly to finish first and second, just 6.23sec apart.

Who was third? Why, Villeneuve, of course. He had qualified only 11th, very unhappy with his Ferrari’s handling in the dry – “It was like a big red Cadillac” – but, as the race progressed, and the downpour set in, he began to dredge a modicum of speed out of it and its Michelin tyres. However, on lap 40 (of 63), he came up to lap Elio de Angelis’ Goodyear-shod Lotus at the hairpin, and the two cars collided. Both drivers spun, but both also got going again, Villeneuve now handicapped by a loose front wing. As, characteristically undaunted, he continued to race at full pelt, the airflow licked around it and the nose cone to which it was attached, gradually deranging the front bodywork ever more luridly, and finally bending it up and in front of the cockpit so that he could see past it only by craning his head from side to side; a loss of front downforce, one felt, must have been the least of his worries.

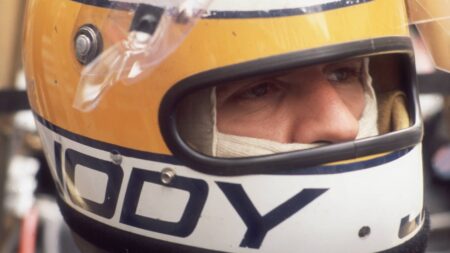

Villeneuve and 126C won two GPs in 1981

Eric Vargiolu/DPPI

Anticipating a likely black flag, unequivocally predicted as a cast-iron certainty by Jackie Stewart who was doing live TV commentary, Villeneuve hatched a plan. The details of what happened next were little reported at the time, but they were witnessed and later written down by the one photographer who was standing resolutely at the hairpin, soaked to the skin, as the rain continued to fall unremittingly: Richard Kelley. “Gilles’ only chance was to deliberately break the nose cone and front wing clean off under braking,” he wrote, “and the hairpin was where I thought he would do it. Sure enough, a few laps later, he absolutely buried the brake pedal, slamming the Ferrari’s front end onto the pavement. The nose and front wing duly broke free as they jammed down onto the asphalt.”

Villeneuve adroitly controlled the resulting tank-slapper, which Kelley described as “big”, and, yes, he completed the race in a Ferrari shitbox shorn of its nose cone and front wing, in teeming rain, finishing third, having lapped everyone except the two men ahead of him. Eleven drivers spun off or crashed out, and one (Jones) retired voluntarily. Even Laffite, who won, said afterwards: “I didn’t like driving today.” Watson, second, went farther: “Today’s conditions were the worst I’ve ever raced in.” Villeneuve? “Oh it wasn’t too bad,” he said. Rock ape? If you insist. But a genius, too.