MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

This weekend’s Hungarian Grand Prix is pivotal – there being nine races either side of it in the schedule. Sebastian Vettel’s title rivals will be running out of time from here on. Indeed, statistics indicate that it will be too late for them to make their move should they fail to knock a sizeable dent in the German’s points lead this Sunday.

Twenty-eight of the 63 Formula 1 World Championships completed since 1950 have consisted of an odd number of rounds, from the seven of 1950 and 1955 to the 19 of 2005, 2010 and 2011.

(We’ll keep our even-numbered statistical powder dry for 2014.)

The driver atop the points table at the conclusion of the middle GP of these odd seasons has gone on to become that year’s world champion on 23 occasions. Giuseppe Farina, Alberto Ascari, Juan Manuel Fangio (twice), Mike Hawthorn (tied with Stirling Moss after six rounds in 1958), Jack Brabham (twice), Graham Hill, Denny Hulme, Jackie Stewart (thrice), Jochen Rindt, Emerson Fittipaldi, Niki Lauda, Jody Scheckter, Michael Schumacher (on four occasions), Fernando Alonso, Jenson Button and Vettel have rammed home the benefit of a strong first half to a campaign.

There are exceptions to every ‘rule’, of course – and Vettel is among them. In 2010, having finished seventh in the British GP, he departed Silverstone nursing a 24-point (16.6%) deficit to McLaren’s Lewis Hamilton and lay fourth in the overall standings. Four months later in the dusk of Abu Dhabi he became the world champion for the first time – by four points.

Remarkably, the man he pipped on that occasion had left Silverstone staring across a 47-point (32%) chasm to Hamilton. Alonso finished out of the points at the British GP. Had he handed back sooner the position he gained from Renault’s Robert Kubica by short-cutting Vale/Club he would have avoided the drive-through penalty that cost him the points that cost him the title.

Hamilton, in turn, slid to an eventual fourth in the standings, though he, too, stood a mathematical chance of winning the title at Abu Dhabi. As did Red Bull’s feisty – “Not bad for a number two, eh?” – Mark Webber, the winner at Silverstone.

This was not the first time that Hamilton and McLaren had let it slip in the second half. In 2007, the super-rookie finished third at Silverstone and departed with a 12-point advantage over team-mate Alonso. The man who defeated the pair of them in the British GP, however, would be crowned that season’s world champion – and Ferrari’s Kimi Räikkönen spanned an 18-point (25.7%) gap to be so.

Silverstone had also seen Jacques Villeneuve make his move some 10 years before, the Williams driver winning the British GP after title rival Michael Schumacher suffered a wheel bearing failure when holding a comfortable lead. This swing meant the Canadian was suddenly just four points (8.5%) in arrears and back in the hunt.

Schumacher’s retirement that day was an indicator of bad things to come: world champions elect tend not to retire from the middle GP. They tend to win it – 13 times since 1950 – or at the very least finish in the top five: two second places, two thirds, five fourths and two fifths. The extended points system (as from 2003) allows more flexibility but champions elect rarely have to stoop low.

Only Ferrari’s Jody Scheckter of the 28 eventual champions we are referring to finished outside the points. He was seventh in the 1979 French GP at Dijon after a pit stop for fresh rubber.

Retirements from a middle GP are ultra-rare for champions elect, too: Schumacher was halted by a Ferrari engine failure at Magny-Cours in 2000 and Nelson Piquet’s Brabham suffered throttle failure in Montreal in 1983. And that’s it.

Piquet is also unusual in that both his world titles – 1981 and 1983 – were achieved via second-half charges. In 1983, he left Canada three points (10%) behind Renault’s Alain Prost. Two years before he had been 11 (29.7%) behind Williams’ Carlos Reutemann after finishing third in a two-part French GP at Dijon. His hard-to-fathom Argentinean rival, who was a distant 10th that day because of a worsening misfire, would soon be telling journalists that he felt fated not to become that year’s world champion despite his handy points advantage.

It’s difficult to imagine Vettel thinking as much let alone saying it to the fourth estate. The ring of confidence that surrounds his demeanour and performances irks many but undeniably is a very useful attribute in a selfish pursuit. He arrives at the Hungaroring holding a 34-point lead over Alonso and has a further seven in hand over Raïkkönen.

It has been suggested that the new low-degrading Pirellis – and a reduction of the pit lane speed limit to 80km/h – might be of strategic benefit to Ferrari and Lotus in Hungary. They will be hoping so.

What they really need, however, is another reliability glitch for Vettel’s Red Bull. A big fat zero for him and a win for Alonso would narrow their gap to nine points with nine races to go. Game on.

A victory for Vettel, however, would put him at least 41 points ahead of his nearest rival – if Alonso finishes second. That’s a 22.5 per cent margin. As Alonso (almost), Räikkönen and Piquet have shown, that’s not necessarily game over – though it would probably go down to the wire, as it did in 1981, 1983, 1997, 2007 and 2010 – but Vettel’s odds would shorten to less than evens.

P.S. Vettel has never won the Hungarian GP.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

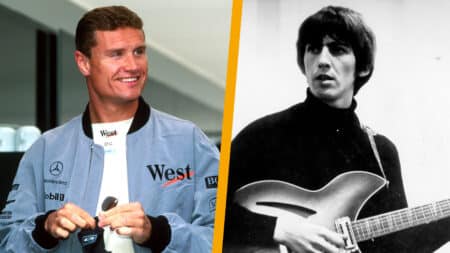

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song