MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Click here to buy the lead image.

Familiar whipping boy Qualifying is to be revamped again. I’ve read the proposals and concluded that they might work – i.e. improve the show by shaking up the grids – or that they might not.

Team bosses have voted in favour of an item whose details have yet to be thrashed out and ratified by the governing body. So the only sure aspect is that stewards would have to be eagle-eyed as eliminated drivers peel off in quick succession.

Blocking en bloc?

There was a simpler time when teams fitted soft rubber to cars running on fumes – and boost wound up tight – and then went for it: push Pedal A! That was the time when this simple writer sat religiously through every Qualifying session.

The complications since have left me cold in the way that algebra did back in the day (of fumes and quallies).

If pure speed is not to be the defining parameter it might as well be pure chance.

Actually, is that such a bad idea? That would definitely shake up the grids.

Here’s a suggestion: have practice, if you must, and award points to the fastest half-dozen or so – and then decide the grid by ballot, hold the race and award points in the usual fashion, plus a few extra based on the number of places gained and one, as was the case before 1960, for fastest lap.

That would reward the quickest and most aggressive as well as the victor.

As to luck, well, that would even itself out over the season. If it didn’t, tough!

Pulling ones grid position from a hat was the racing norm when hats were all the rage – and cars started individually at regular intervals and raced against the clock.

Once the sequence of manufacturers had been set in this fashion, team managers were often free to decide where to place which drivers within their in-house running order.

Thus Fernand Gabriel – allocated 1A – sat on the first Grand Prix pole position at Le Mans 110 years ago. That 6am getaway and clear road ahead didn’t do him much good, however, for his Lorraine-Diétrich snapped a radius rod on the first (64-mile) lap.

(Qualifying for a voiturette race near Paris that same year covered six days and 48 laps of its 20-mile-long venue!)

As GP circuits tended to become shorter, so cars began to be released in pairs and at reduced intervals – yet their starting order was still dependent on happenstance.

Track position wasn’t yet the golden ticket in events that could last eight hours or more and which always took a heavy mechanical toll, but the fact that Mercedes’ 1-2-3 in the greatest race of the pre-WWI age, the 1914 French GP at Lyon, was achieved by cars numbered 28,40 and 39 – the last three to start were all Mercs – made the achievement all the greater.

Even when the 1922 French GP at Strasbourg used a massed (rolling) start, its grid order was decided by ballot. Oddly – and evenly, I guess – numbers 1, 2, and 3 DNS-ed and so Fiat’s Felice Nazzaro, the eventual winner, started from an ersatz pole.

Ballots (not the cars designed by Ernest Henry) arranged subsequent massed standing starts, too.

It wasn’t until the 1933 Monaco GP that qualifying became more tenths. Well, seconds at least.

Those stopwatches didn’t start at the behest of drivers frustrated by baulking cars on a street circuit already deemed unfit for purpose. It was suggested to the organisers by the French doyen of motor racing, Charles Faroux, and followed the example set by the Indy 500.

It hadn’t always been thus at the Brickyard. Louis Strang was on pole for its inaugural 1911 International Sweepstakes solely due to clerical efficiency: the entry from Case Company, more famous for agricultural equipment, arrived before any of its rivals’.

That first-through-the-post system survived until 1915, whereupon Howdy Wilcox put his Stutz on pole with a single timed lap: 1min 31sec (98.9mph).

The familiar four-lap average was introduced in 1920.

Europe remained divided on the topic. A minor race in Finland followed Monaco’s example, as did several of France’s second-tier regional GPs, but only Monaco of the six Grandes Epreuves of 1934 featured a grid decided by lap time.

The 1935 AIACR European Championship also included just one timed grid: the Swiss GP, naturally.

Nobody seemed to mind, especially when the racing was as exciting as that year’s German GP. Alfa Romeo’s surprise winner Tazio Nuvolari drew the middle slot in the front row for that one.

Ballot was used as late as the 1939 Belgian GP.

That the 1933 Monaco GP provided arguably the greatest lead duel and was won by a worthy pole-sitter – Bugatti’s Achille Varzi – helped, but the main reasons that timing eventually won out were its absolute aptness and fundamental fairness.

It ticked the boxes.

That hasn’t changed. But everything else has.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

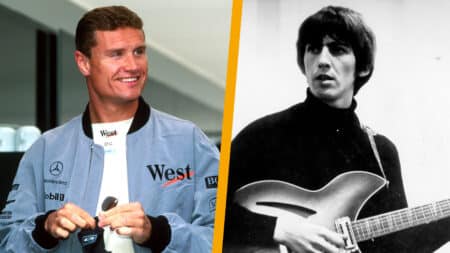

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song