MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Who is the most influential designer to have worked in Grand Prix motor racing: Vittorio Jano, Colin Chapman, Adrian Newey?

It’s a trick question. And my answer is: the man who fashioned the pug-ugly, dog-slow Eifelland Type 21 of 1972.

Germany’s Luigi, aka Lutz, Colani is an immodest man of straggly ’tache, baggy cricket sweaters, cravats, clogs and cigars. He lives in a Bond-villain-esque baroque Westphalian schloss – with a moat, of course – where he conceives a bewildering array of bewildering designs when not making forthright pronouncements about aptitude (his) and ineptitude (most others).

He takes his cues from nature: aeroplanes – from single-seaters to 1000-plus – that look like birds, ships that look like fish, etc. Biodynamic, he calls it. Earth is round, its orbit elliptical, so why this conservative-creative obsession with straight lines? is his thinking, his ‘bubble’.

Born in 1928 to artistic parents of Swiss and Polish descent, he trained as a sculptor before studying aerodynamics at the Sorbonne and then being headhunted in the early 1950s by McDonnell Douglas to work with cutting-edge (ahem) materials. Go-ahead Simca tempted him back to Europe a few years later, and it was his streamlined Panhard flat-twin tiddlers that provided Deutsch et Bonnet with much success in long-distance sportscar racing. (In a rare admission, he concedes that Chapman’s Lotuses were better at faster, lighter.) He also penned an effective Alfa Romeo-Abarth mini-GT and designed a mould-breaking all-fibreglass – take that, Mr Chapman! – monocoque sportscar based on BMW’s 700. A need for speed and love of cars has since seen him extract serious mph and mpg from outlandishly bodied Ferraris, 2CV-based buzzboxes and Mercedes-Benz tractor-units.

His foray into Formula 1, as by now you might have anticipated, was bizarre, involving as it did a tempestuous manufacturer of caravans and his one-armed racer twin, Heinz. When Günther Henerici, who had already spent part of his fortune helping Siegen’s Rolf Stommelen rise through the junior formulae, decided to go all in, he asked Colani, by then the ‘Popstar of Design’ – part Salvador Dali, part Roy Wood of Wizard – to clothe his F1 project. The resultant bodywork was a swoopy piece: rounded full-width nose with ovoid inlets; enveloping top-sides that curved up to the rear deck and beyond to a large-Gurney Flapped affair with integral endplates; cockpit conning tower with a cold-air intake directly below the driver’s eye-line and central periscope mirror atop a stalk above it. It was nicknamed ‘The ‘Whale’.

Colani proclaimed that his organic approach would render all other F1 cars antiquated overnight. Er… his overheated and lacked downforce, and would have to be gradually de-Colanised. By the time of its (un)competitive debut at Kyalami’s South African GP on March 4, the awful Eifelland featured exposed side radiators, a separate rear wing, and a raised tea-tray nose from a March 711. Stommelen qualified 25th (of 27), received a push on the dummy grid and thus was disqualified, slogged to 13th place, two laps in arrears, in any case, and was reinstated on appeal.

Colani proclaimed that his organic approach would render all other F1 cars antiquated overnight. Er… his overheated and lacked downforce, and would have to be gradually de-Colanised. By the time of its (un)competitive debut at Kyalami’s South African GP on March 4, the awful Eifelland featured exposed side radiators, a separate rear wing, and a raised tea-tray nose from a March 711. Stommelen qualified 25th (of 27), received a push on the dummy grid and thus was disqualified, slogged to 13th place, two laps in arrears, in any case, and was reinstated on appeal.

The car’s lack of pace wasn’t entirely Colani’s fault – it didn’t help that it was underpinned by March’s unloved 721 – but it was clear that F1 was too square for this hipster. His squad – ‘Team Dream’, according to Ronnie Peterson – wore headbands fer Chrissakes. Yep, his ‘work’ here was done. The bluffer!

Yet I wouldn’t be surprised to discover that super-successful yet modest Newey has cast envious glances in Colani’s direction. For when word leaked that he felt constricted at Williams, constrained at McLaren, the rumour mill linked Newey with the possible design of an LSR car, say, to break the Sound Barrier, say, or an America’s Cup yacht. Indeed, such wide-ranging opportunities were ‘said’ to be contributory to his joining Red Bull Racing. (There’s still time, of course, for him to be given wings of a different nature.)

Newey has helped to generate virtual RB racers for Gran Turismo vid games, whereas Colani has lived that diverse designer lifestyle for more than 60 years: ceramics for Villeroy & Boch, headphones for Sony, shoes for Dior, uniforms for Swissair, cameras for Canon – its trendsetting T90 SLR – binoculars for Carl Zeiss, furniture for Asko, design studies for Mazda and VW.

Rockets and underwater oil tankers, a house with bathroom, kitchen and bedroom pods accessed via a motorised lazy Susan, bicycles and motorbikes, carpets and wall-hangings, hi-fis, PCs and TVs, sunglasses and glassware, clocks and watches, toys and the sexiest scale-model of a steam locomotive that you’ve ever seen – trans-Siberia, powered by coal dust – plus those essential household items, the teapot and streamlined grand piano.

Not every idea of his has gone into mass-production. (Ya don’t say!) Feasibility studies are for dullards, not Colani. His course is set unswervingly for the distant future, imperfect or otherwise. Where the next dime – or short-term tenth of a second – is coming from does not interest him.

Not every idea of his has gone into mass-production. (Ya don’t say!) Feasibility studies are for dullards, not Colani. His course is set unswervingly for the distant future, imperfect or otherwise. Where the next dime – or short-term tenth of a second – is coming from does not interest him.

It’s easy to scoff – and easy for him to boast, true – but to step inside acclaimed architect Zaha Hadid’s whale’s belly of an Aquatics Centre for London 2012 is to be persuaded that Colani, a venerated design giant in Japan and China, was way ahead of his time. Now 83, unabashed and unadulterated still, he insists, between puffs and smoke-rings, that this remains the case. By 30 years. At least.

Even his F1 car provided a legacy of sorts. Stommelen had wrestled it through seven Grands Prix by the time Henerici packed up, sold up and cancelled Len Terry’s nascent design for 1973. Rolf contested one more using his own money before London-based Dublin car dealer Tony ‘Monkey’ Brown bought the car from Bernie Ecclestone, who had purchased the team lock, stock and two smokin’s for its DFV engines.

Brown promptly entrusted it to a callow, bearded Ulsterman ‘Stommelen’. Thus a 26-year-old John Watson’s first experience of F1 power and speed was accrued aboard this krazee kar – its periscope still defiantly up – in an oddball Formule Libre September shindig at the barking-bonkers Phoenix Park in Dublin. It arrived late, complete with dicky clutch and oil leaks, missed the first heat and squirted petrol over him in the second – but not before he set joint-fastest lap.

Brown promptly entrusted it to a callow, bearded Ulsterman ‘Stommelen’. Thus a 26-year-old John Watson’s first experience of F1 power and speed was accrued aboard this krazee kar – its periscope still defiantly up – in an oddball Formule Libre September shindig at the barking-bonkers Phoenix Park in Dublin. It arrived late, complete with dicky clutch and oil leaks, missed the first heat and squirted petrol over him in the second – but not before he set joint-fastest lap.

“The car’s condition was very poor,” says ‘Wattie’. “But I was naïve – and would have sat on a bed of nails to drive a GP car – so I trusted that it had been well prepared. Which was stupid because Phoenix Park was probably the most dangerous circuit in Europe: 140mph bends lined by trees with a single straw bale in front of each one. Only when Paul Michaels’ Hexagon of Highgate got involved and prepared the car for me for the Victory Race at Brands Hatch in October did I realise how bad it was: mindboggling slop in the rear suspension, etc.

“Colani suffered a lot of derision from within F1, but I wouldn’t knock him, however. He’s an individualist, a lateral thinker, a risk-taker – something that F1 lacks today and is all the poorer for it. The current regulations read like a form from the Inland Revenue.

“The Eifelland – that March, whatever you want to call it – served my career well.”

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

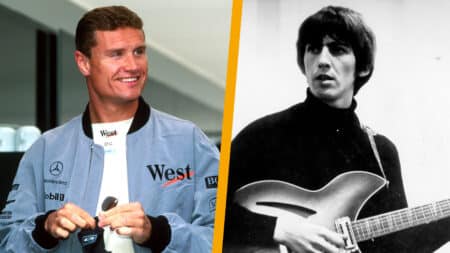

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song