MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Talk of Lewis Hamilton’s forming of a superteam alongside Sebastian Vettel has been cut dead in its chats by Red Bull’s re-signing of a rejuvenated Mark Webber.

There has been rumour, too, of his realigning with Fernando Alonso at Ferrari – although it was much more likely that Webber would swap his blue Red Bull for Italian red. And now we know that that’s not going to happen either.

Don’t be surprised, therefore, if the Scuderia employs the improving Felipe Massa for another year in the interests of stability; Alonso’s that is. Indeed, I have the suspicion that this silly season will be boringly sensible. With six world champions, plus two more potential top dogs – Webber and Romain Grosjean – and five winning teams, plus two potential others – Lotus and Sauber – on the grid, we can expect most drivers to sit tight given the opportunity to do so. Because 2013 is impossible to predict, it’s better the devil and/or details you know. Red Bull and Webber clearly think so.

The only ‘prime’ seat up for grabs might be Michael Schumacher’s at Mercedes-Benz. Paul di Resta would jump at it; a driver of Hamilton’s status might consider such a move sideways at best, a gamble at worst. However, given McLaren’s recent performances and the tone of the resultant (broadcast) radio messages – brittle on the driver’s part, cloyingly unctuous on the team’s – Hamilton might also consider the grass to be more silvery in Stuttgart and Brackley.

McLaren’s slide is in stark contrast to its days as the greatest superteam, i.e. the best two drivers in the best chassis/best engine combo. In fairness, today’s field is too open, too full of bulls of various hues, for there to be a repeat of its Ayrton Senna/Alain Prost domination of 1988-89: 25 wins from 32 grands prix in MP4s /4 and /5, with Honda turbo and then atmo power.

Such occurrences in most cases tend to be supernova bright before imploding darkly under the weight of their egos and expectations. That’s certainly what happened to the first such, 80 years ago, when Tazio Nuvolari and Rudolf Caracciola were ‘united’ with the original successful GP single-seater, designer Vittorio Jano’s Alfa Romeo Tipo B.

‘Caratsch’ had made his name driving brutish Mercedes-Benz with finesse and cunning. In 1931, he had become the first non-Italian (of only two) to win the round-Italy Mille Miglia. A team man, it was with heavy heart that he signed for Alfa when it became obvious that his long-term employer planned to withdraw from competition. Though taken aback that his new car was to be painted German white rather welcoming works team red, he was willing to risk it. Plus he had no option.

Nuvolari adopted a hectic Senna-like pace at Monaco while Caracciola – think Prost, only better in the wet – stealthily ascended the order. The gap between red and white shrunk in the closing laps, Nuvolari hampered by fuel starvation and at the mercy of his ‘team-mate’, only for Caracciola to hang back and finish a dutiful second. His Alfa would be (increasingly, and finally completely) red thereafter.

Caracciola at the Nürburgring in 1937

Not that this was an end to the shenanigans. At last at the wheel of a Tipo B instead of a two-seat ‘Monza’ model, Caracciola was designated to win July’s French GP at Reims, only for Nuvolari to disobey orders, pass the pits “going in several directions at once”, and head a 1-2-3: all the right notes – but not necessarily in the right order. Two weeks later at the Nürburgring’s German GP, mechanics had to administer a go-slow at a Nuvolari pit stop to ensure that Caracciola prevailed.

Both men got on well, respected each other and were equals in speed – this was before injuries sustained in a 1933 Monaco practice accident robbed the German of that last precious tenth – yet they had unleashed unstoppable destructive forces. Alfa Romeo saw no need to further press home so obvious an advantage and pulled out; headstrong Nuvolari demanded a greater say in the running of the surrogate works team but was rebuffed by boss Enzo Ferrari and so switched to Maserati; and Caracciola wanted no part of another Latin maelstrom and thus co-founded a more cosy outfit alongside debonair Louis Chiron. This time his Alfa was white – with central blue stripe – out of choice.

Not all ‘superteams’ are so fractious. In the aftermath of Alberto Ascari’s fatal accident – and with it the puncturing of Lancia’s already much-delayed programme – a young Stirling Moss was able to sit hawk-eyed yet content in Juan Manuel Fangio’s tutoring wheel tracks at Mercedes-Benz in 1955, only for their employer to also call time at a successful season’s end. And Jim Clark and Graham Hill gelled at Lotus in its new-age Cosworth DFV-powered 49s of 1967, although it was only after its totem had been killed at Hockenheim the following year that the shattered team fully appreciated the latter’s fighting qualities.

Superteams in truth are a rare and unnecessary extravagance, a negative influence on all but the very few. No matter how equally matched are your aces, there will always be a blue-eyed favourite. Webber knows this, but is willing to risk it; Massa knows it, but has no option; but Button does not.

And nor should he, because it’s been grey-vague at McLaren since his arrival. Such confusion is a factor in the increasingly unsuper 2012 demeanour and results of Britain’s ‘superteam’. Somebody there needs to make their mind up soon, for Senna-and-Prost red-and-white it’s not.

Hamilton might yet press that Mercedes button.

And Red Bull might yet implode if Webber becomes world champion.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

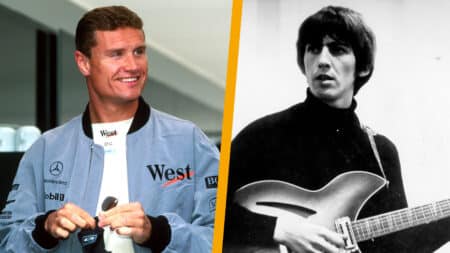

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song