MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

As this week in Barcelona has shown, testing throws up some interesting sights – none more so than the six-wheel wonders of the 1980s

Keke Rosberg’s championship-winning Williams of 1982 was intended as a six-wheeler.

FW08’s monocoque was stubby and its fuel tank mounted relatively high behind the driver to accommodate the extra 25cm of a twinned-driven-rear-axle arrangement.

Reduced frontal area and drag, increased downforce and traction – bingo!

But circumstance and finance worked against this ambitious plan – and then Frank Williams voted against it.

“It wasn’t banned because it was a six-wheeler,” says Williams’ chief engineer/aerodynamicist Frank Dernie. “It was banned because it was a 4WD. All agreed at a FOCA meeting that they didn’t want it – but Frank hadn’t realised our six-wheeler was 4WD.

“When he briefed us about it, during one of our lunchtime discussions over a sandwich, Patrick [Head] was as angry as I have ever seen him.”

The six-wheeler was hatched because Williams was worried that it was lagging not only behind the turbos but also fellow DFV devotee McLaren, with its carbon fibre monocoque.

“It would have been competitive, quick,” says Dernie of the six-wheeler. “To put it into perspective, the lift-to-drag ratio of FW08 was 8.2, if I remember correctly, and FW08B [the second-iteration six-wheeler] was not much more.

“But the final [quarter-scale] wind tunnel model of the six-wheeler that would have gone into production had a lift-to-drag of 13-point-something.”

With neither front nor rear wing, any necessary trimming was to be supplied by a Gurney-type flap at the bodywork’s rear.

Williams having its own wind tunnel, purchased from Specialised Mouldings and updated by Dernie and a young Ross Brawn to feature a rolling road, was paying dividends.

Dernie: “The biggest problem with traditional ground effect cars is that their downforce is generated a very long way forward and so you need a draggy rear wing to balance it.

“The big plus with the six-wheeler was that its sidepods ran comfortably inside the [narrow] rear tyres, right to the back.

“The Lotus 80 [of 1979] had skirts right to the back, too, but they were S-shaped [to fit around standard-sized rears] and used to jam, causing all sorts of problems.

“I managed a sufficiently rearward centre of pressure, without too much loss from the underbody, to do away with wings; the car had a slotted-flap-type underbody, part of it around the exhaust, part of it in the normal place.

“I couldn’t have done that with a four-wheeled car. When skirts have to stop ahead of the rear tyres, you’re knackered.”

Alan Jones tested the first iteration, FW07D, at Donington Park in November 1981, a fortnight after his farewell Las Vegas Grand Prix victory.

Frank Williams was hoping that his number one might reverse that decision to retire once he had seen – and driven – the future.

Unfortunately, it had the opposite effect.

Not because the car was a dud, but because the weather was so cold – Jones had to pour hot water on his Jaguar’s locks – that a return to Australia had never been more appealing.

Keke Rosberg, Jacques Laffite, Jonathan Palmer and Tony Trimmer, therefore, tested FW08B – as late as October 1982.

“It was quite progressive,” says Palmer. “It was great fun to throw around, to get a bit sideways, because instead of one wheel losing grip and, therefore, losing 50 per cent of your rear-end grip, if one wheel lost grip you still had three others giving you some grip.”

The car showed promise on all types of circuit, from the sweeps of Silverstone to the twists of Croix-en-Ternois, in wet and dry conditions.

It was allegedly a few tenths faster than Alain Prost’s turbo Renault at Paul Ricard, albeit on different days.

Buy any of these on the Photo Store

“Patrick was sure that the only limitation would be, with four driven wheels pointing straight ahead, masses of power-understeer,” says Dernie. “But, after just a few laps of ’Croix, Laffite admitted he’d forgotten it was a six-wheeler.

“If you get the weight distribution right for the tyres and make sure the aero is consistent, there is no reason why it wouldn’t feel like any normal racing car.

“To get the ultimate from it, though, tyres specific to the rear would have been required. At that time, however, we were just running six fronts.

“One of the things we tried was slicks in the wet, on the rear axle only. It worked. I don’t know how long it would have worked because those tests were perfunctory, but I suspect that they would have eventually got too cold.”

Given that Dernie was simultaneously assessing active suspension, that Rosberg was stringing together an unexpected title bid in F1’s craziest season, and a manufacturer supplier of turbo power was being courted, the six-wheeler slipped down the list of priorities and behind schedule.

“We didn’t expect it to be banned,” says Dernie. “Though we thought that maybe it would be once everyone saw how quick it was.

“We didn’t have sufficient time or money to bring it to fruition. We only did one [Hewland] gearbox, for example. Its casing was completely different because the suspension mounts were different. The gear linkage was unique, too.

“Because I had done my apprenticeship at a gearbox company [David Brown], I knew you had to have different-handed spiral bevels front and back. If you have a gear receiving torque the wrong way, it fails.

“We would have had to make lots of new bits before racing it, and inevitably it was going to be a heavier than a normal car.”

So, despite – or perhaps because of – an impressive and probably optimistic simulated lap time of Paul Ricard – “I wrote that software and I have to tell you that it was very crude,” admits Dernie – Williams’ six-wheeler was shunted into F1’s technological siding.

Where it sat next to March’s six-wheeler of 1977.

Keen to board the promotional bandwagon towed by Tyrrell’s P34 six-wheeler, joint team boss Max Mosley had mechanic Wayne Eckersley raid the parts bin and build what was a full-scale model: dummy engine, empty gearbox, F3 uprights.

But when a doubtful press called March’s bluff, a runner was readied within a fortnight.

The March ‘launch’

Designer Robin Herd was of the opinion – and Dernie agrees – that P34’s 4-2-0 arrangement was fundamentally flawed; approximately 40 per cent of its drag was created by large rear tyres that also ensured its frontal area was unchanged.

So he placed his extra axle, driven and fitted with smaller, narrower wheels, at the rear

“Frontal area greatly reduced, far less disturbance of the flow to the rear wing [further back relative to the CoG], plus a substantial gain in traction,” says Herd. “The increase in top speed was massive.

“It would have dominated – until everyone did the same.”

Howden Ganley drove it: “Was it any good? That depends on one’s point of reference.

It certainly pointed out a good route for development.

“It was an interesting car that had a few teething problems.

“I’ve read that I tested it with only two wheels driving. Maybe somebody did – Ian Scheckter perhaps – but I didn’t.

“Had the FIA not stepped in I expect we would have seen six-wheelers racing – at enormous cost.”

Six wheels, but SuperSwede still slides

Money was something March did not have – despite royalties from Scalextric for its popular 2-4-0 model – and new parts and testing were strictly rationed.

“The cost to do it properly would have been that of an entirely new car,” says Herd.

Instead 2-4-0 remained an unraced bolt-on kit for existing cars rather than a resolved whole.

Herd: “In my view, P34 was incomprehensibly misguided thinking. But Ken Tyrrell, all credit, had the cash.”

“That Tyrrell was competitive despite it being a six-wheeler,” says Dernie.

Ah, the back-to-front world of F1’s six-wheelers.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

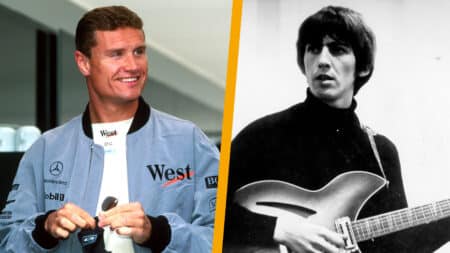

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song