MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

How France eventually conquered Formula 1, one Swedish weekend

The sport’s mother country has resumed her rightful place on the Formula 1 calendar.

Though it’s a shame that the French Grand Prix of 2018 will be held at Paul Ricard, which nowadays looks more like an art installation than a racing circuit – a Signes of the times, I guess – it’s a relief that it’s happening at all.

For the nation that writes the rules and regulations has been absent from the top table since 2008.

But then it’s been surviving off its crumbs since before 1950.

Were it not for Renault and Alain Prost – who famously split in 1983 – France would be F1’s ‘sick man of Europe’. For between them they provide 86 of its 131 driver/constructor F1 victories.

Results aren’t everything, of course.

Who didn’t warm to the je ne sais quoi of wild-eyed René Arnoux, happy-go-lucky Jacques Laffite, little-boy-lost Patrick Depailler, smoothie Patrick Tambay, handsome François Cevert and the slicks-in-the-wet cavalier spirit of Jean Alesi?

That they under-delivered is part of their charm. Part of their nation’s make-up perhaps. Prost reckons his popularity at home dipped when he started to win big with McLaren.

There’s something in this.

Renault the constructor tossed away its turbo advantage during the late 1970s/1980s – blew it, big time – and only started winning championships when it ran out of Oxfordshire.

And rocket scientists Matra, who provided the best chassis of the late 1960s, only won – nine times – when powered by a British engine, driven by a British driver, run by a British team.

That’s not to say chassis from Norfolk, Bucks and Oxon haven’t prospered with Renault power behind them. It’s just that the country that gave us Panhard et Levassor, Richard-Brasier, Peugeot, Ballot, Bugatti and Delage has since WWII provided a glut of GP ‘citrons’.

There’s the mysterious SEFAC – the French do like an acronym. With good reason. The Société d’Etude et de Fabrication d’Automobiles de Course featured parallel, coupled contra-rotating four-cylinders and was chronically underpowered and vastly overweight as a result.

Having completed a few leisurely practice laps for the 1935 French GP, it scratched from the race.

Reappearing at Reims three years later (pictured below), it actually started – but retired after three laps.

Incredibly, there was talk of reviving this embarrassment in 1948, under the name Dommartin. Luckily, the money ran out.

By which time a government desperate for GP success had funded the Centre d’Etudes Techniques de l’Automobile et du Cycle. The resultant car, designed by Albert Lory of 1920s Delage fame, was called CTA-Arsenal.

There’s a clue there.

Though it handled abominably, Raymond ‘Coeur de Lion’ Sommer volunteered to drive it – Pour La Gloire! – in the 1947 French GP at Lyon-Parilly.

It broke a driveshaft at the start by way of merciful release.

(In the interests of fairness, the same fate befell Sommer when he gave the BRM V16 its competition debut at Silverstone in August 1950.)

And quite what the apparently otherwise sensible Messieurs Deutsch and Bonnet were thinking with their supercharged 750cc flat-twin – based on their Monomill traction avant one-make racer – is difficult to fathom.

But at least it raced – in the 1955 Pau GP – unlike the Sacha-Gordine of 1953.

The latter’s specification – rear-engined and with expensive cast magnesium everywhere – and intended programme across a spread of formulae read like a Hollywood script, and proved just as fanciful. The project, deep in the red, faded swiftly to black.

And, yes, its boss was a film producer.

Surely Bugatti would/could/should get it right. Founder Ettore was dead, but designer Gioacchino Colombo arrived via success at Alfa Romeo, Ferrari and Maserati. Unfortunately, his complex Type 251 proved too much for this reconstituted marque.

Its transverse straight-eight – in back-to-back blocks of four – was sited behind the driver; and its rigid-axle de Dion tubes front and rear were suspended via pushrods and rockers operating inboard coil springs.

It was heavy, unstable and 19secs off the pace during practice for the 1956 French GP at Reims. Dapper Maurice Trintignant did his best but was not unhappy when dirt jammed its throttles after 18 laps of tugging at the tail.

Thus French GP cars of the 1950s were primarily about Le Sorcier Amédée Gordini, working miracles with what little he had. And when that ran out, in 1957, that was that until Matra’s arrival in 1968.

Incredibly, not until June 1977 did a French driver in a French car powered by a French engine, run by a French team sponsored by a French company win a world championship Grand Prix.

Guy Ligier mixed Gallic flair and flare-ups with a nuggety toughness befitting a rugby forward of renown. His equipe reflected that.

Benefiting from an influx of talent after Matra-Simca’s withdrawal from sports car racing at the end of 1974, Ligier’s first season of F1, 1976, resulted in three podium finishes and a pole position.

Zero points from the first eight rounds of 1977, therefore, should have been deeply troubling. Laffite being Laffite, however, he was sure it would come right.

And though he often seemed keener on golf and fishing, he could invariably turn it on given a good car.

JS7, co-designed by Gérard Ducarouge and Michel Beaujon, was conventional if a little bulky. Fab in French blue, it sounded fantastic thanks to its Matra V12 and was awarded more than a whiff of chic, danger and romance by its Gitanes livery.

Laffite had qualified it on the front row for the Spanish GP at Jarama and set fastest lap after a pitstop because of a loose wheel.

Yeah, it would come right.

That feeling intensified when he set fastest lap during morning warm-up for the Swedish GP at Anderstorp: the car felt great – even after he’d nerfed the rear of Gunnar Nilsson’s Lotus at the start.

Though JS7 was no match for Mario Andretti’s Lotus 78 ‘wing car’ – none were – Laffite bided his time before beginning his push at mid-distance, on a track with long, banked, constant-radius corners that were hard on tyres.

In short order he picked off Jochen Mass’s McLaren M23, Patrick Depailler’s six-wheel Tyrrell and the McLaren M26 of James Hunt to run second. He even began to close on Andretti.

The latter, managing a 15-second lead, appeared to have it in the bag. He was worried, however. With good reason. The injection’s metering unit had vibrated from weak to rich. This decreased mpg as well as causing a regular hesitation from lap 10 on.

With three of the 72 laps remaining, Andretti had to sweep into the pits for another five gallons.

Two races later, bedecked in corporate yellow, Renault arrived in F1 with its stumpy car and flat-sounding turbo. I can’t deny that I’m glad Ligier (and Matra) had beaten it to le punch.

PS I’m glad that the German GP is to make its return in 2018, too.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

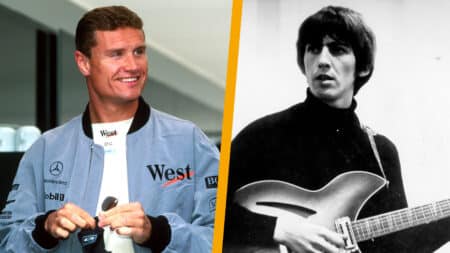

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song