MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Austria was the second successive Grand Prix in which the team that locked-out the front row lucked-out in terms of victory.

In Canada, Mercedes-Benz proved how hard it’s pushing the limits to win so apparently easily. Last Sunday, Williams proved that winning is a habit hard to relearn.

When wise owls like Pat Symonds and Rob Smedley decide to run their own race rather than react to their rival’s, you can be sure that there is a damn good reason for it.

I can’t help thinking, however, that Valtteri Bottas is today wondering what might have been.

As must have team-mate Felipe Massa after the pit stop hiccup of Montreal.

There were times when Williams often locked-out the front row before romping to victory. Equally, there was a time when (Sir) Frank operated out of a public telephone box in Reading. He has seen it all before.

His team, for instance, copped flak – rubber bullets? – for Adelaide 1986.

The FW11-Hondas of Nigel Mansell and Nelson Piquet sat on the front row with a second per lap in their pocket over the McLaren of fellow title aspirant Alain Prost. Had Williams stuck to its plan of a tyre stop rather than switch to a non-stop strategy – admittedly on updated advice after Goodyear’s examination of Prost’s rubber discarded because of a puncture – either of its drivers might have been crowned world champion.

Then there was Spa 2001.

Juan Pablo Montoya was sensational on a drying track to take pole by nine-tenths from the FW23-BMW of team-mate Ralf Schumacher, who in turn had 1.7 seconds in hand over the Ferrari of big brother Michael.

That was the good bit.

The first start was aborted when Heinz-Harald Frentzen’s Prost, fourth on the grid, stalled.

So, too, would Montoya moments before the second formation lap.

Ralf, now on pole by default, led at the start, but Michael swiftly asserted his authority.

Not much later Prost’s Luciano Burti thought he had spotted a new overtaking spot on the inside at Blanchimont. He hadn’t. Big hit. Red Flags.

This time it was Ralf’s turn to suffer outrageous fortune.

Montoya’s rear wing had been discovered to be broken and it was decided to replace his team-mate’s on the grid as a precaution. Unfortunately, the mechanics ran out of time and Ralf was left high and dry on jacks as the field departed on its third formation lap of a harum-scarum day.

Michael Schumacher was untouchable in the race – and completed Alain Prost’s misery by breaking his record of 51 GP wins – yet a brace of Williams-BMWs might have been able to control him had not events conspired to force them to start from the back. I’m sure that Montoya, who retired early because of an engine failure, would have risked giving it the gun after a troubled season, whereas Ralf, with three victories under his belt – Imola, Montreal and Hockenheim – might have played it more cannily.

In the same way, perhaps Williams should have hedged its bets at the Red Bull Ring and allowed Bottas to be more aggressive. That way it might have tipped Mercedes-Benz over its cutting edge once again.

Shoulda, woulda, coulda.

Just like Ferrari at Monza in 1956, when Eugenio Castellotti and Luigi Musso diced for local bragging rights as though in league with the devil, and the team dismissed newcomer Wolfgang von Trips’ practice-crash explanation and suffered two further steering failures as a result.

I think that’s the only case of a three-car lock-out luck-out.

And in the era of two-by-two grids:

Just like Ferrari at Montjuïc Park in 1975, when Niki Lauda and Clay Regazzoni were wiped out under braking for the first corner;

and the ‘Black Beauty’ Lotus 79s of Ronnie Peterson (fuel leak) and Mario Andretti (engine) at Brands Hatch in 1978;

and the Renaults of Prost and René Arnoux in Britain, Germany and Austria – three on the bounce! – in 1981, and at Imola, Zolder, Zandvoort, Dijon and Las Vegas in 1982. Cor, the Régie blew F1 in more ways than one.

One that I particularly remember is Benetton at the Österreichring in 1986.

I thought designer Rory Byrne’s B186 handsome, and though its squiggly United Colors scheme was not to everyone’s taste, I liked it. (The painted Pirelli sidewalls used in Detroit were too garish, however. Tyres, like football boots, are better black.) Talk of 1400bhp-plus from its upright BMW ‘four’, meanwhile, had this teenager in a right old tizzy.

Teo Fabi won pole (159.1mph) by a couple of tenths from team-mate Gerhard Berger, but the local hero took the lead at the start. Thereafter, those green cars blended with the Styrian pastoral backdrop. All seemed serene. 1-2.

But Toleman/Benetton had yet to learn the winning habit in Formula 1, never mind lose it.

Fabi had muffed a gear change over a bump exiting the chicane and was harbouring doubts about the longevity of his buzzed engine. Sure enough, it let go seconds after he had taken the lead from Berger on lap 17.

Then, after 25 laps, Berger pitted for what should have been a regulation tyre stop. Instead he lost three laps because of a damaged battery. He tore back into the race, set a consolatory fastest lap – and finished seventh.

Hey-ho.

Fabi’s race engineer that day was Pat Symonds. He, too, has seen everything. That’s healthy. And that’s why new-look Williams will undoubtedly soon earn itself more chances to shine.

Or at the very least be in a position to luck-in.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

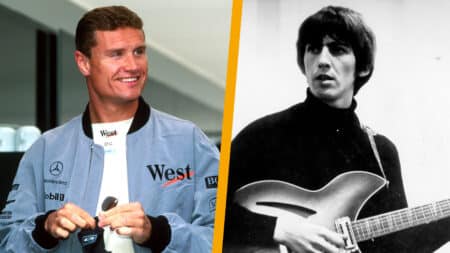

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song