MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

The tricky road to victory, for some it’s far longer than others

All good things come to those who wait – except the luckless late Chris Amon.

Valtteri Bottas, on the occasion of his 81st Formula 1 start, made winning a Grand Prix appear as though it were an everyday occurrence for him, his success in Russia being every bit as accomplished as Pastor Maldonado’s Barcelona 2012 or Jarno Trulli’s Monaco 2004.

The Finn, of course, will be hoping – and is highly likely – to go at least one better very soon, whereas Trulli and Maldonado will forever remain on one.

That the former, so accomplished in most aspects of the job, had to wait until his 119th Grand Prix to get off the mark astounds me still – though not as much as the latter’s mad dog day in the Spanish midday sun.

Maldonado required just 24 starts to step onto the top step, which marks him out as considerably better than average in this regard. Not quite as good as his (probable) role model Vittorio Brambilla (23), but as good as Max Verstappen.

Excluding the 10 men who shared the 11 victories during the period from 1950-’60 when the Indy 500 counted towards the world championship, 97 drivers have won at least one GP.

Of those, 25 are marooned on the one, 33 have scored more than 10, and the remaining 39 provide the filling in the sandwich.

The 25 veer from Trulli to Giancarlo Baghetti, winner for Ferrari on his world championship debut, Reims 1961.

Jean Alesi’s singleton victory, Montréal 1995, was his 91st start and 16th podium visit.

And the latter figure was matched by Patrick Depailler, Eddie Irvine and Mika Häkkinen, who went on to score two, four and 20 victories respectively.

Irvine’s maiden win, Melbourne 1999, was his 82nd start, one more than Bottas. It was a result that launched a surprising title bid against a man who had required 14 more attempts to bother the scorers: Häkkinen.

So, is it better to notch your inaugural GP win precociously early or to learn your craft before making hay?

Baghetti actually won the first three races of his F1 career – the others being non-championship affairs at Syracuse in Sicily and Naples – before fading ignominiously thereafter.

Whereas the likes of Mark Webber (130 starts) and Rubens Barrichello (123), the more rounded members of this elite, went win-less for 253 starts before scoring 20 victories, nine and 11 respectively, between them.

The average across the 97 is 32 starts before that thirsted first win: think Niki Lauda, Alan Jones and Graham Hill.

The average across the bottom 25 is 32.8: think Robert Kubica.

Across the top 33, it’s 33.9: think Hill again.

And across those with between nine and two victories, it’s 30: think Maurice Trintignant. (I’m sure that you do. Often.)

Among the quick studies, who won within fewer than 10 starts, are: Juan Fangio (two), Emerson Fittipaldi and Jacques Villeneuve (four), Lewis Hamilton (six), Jackie Stewart (eight) and Alberto Ascari (nine). And their combined current tallies stand at 143 wins and 16 drivers’ world titles.

Among the slow learners are: Jenson Button (113), Nico Rosberg (111), Nigel Mansell (72) and Felipe Massa (66). Add their scores to those of Barrichello and Häkkinen and their combined current tallies are: 111 wins and five titles.

But though precociousness has it, it’s no guarantee of long-term success, especially if you’re Italian: Ludovico Scarfiotti (four), Luigi Fagioli and Piero Taruffi (both seven), as well as Baghetti, never won again.

And what of Mr Average – or should that be Messrs Mean, Median and Mode? Lies, damn lies and my statistics.

I refer, of course, to those who required between 30 and 33 attempts to crack the F1 code.

These include the aforesaid Hill, Jones, Lauda and Trintignant, plus Fernando Alonso, and James Hunt. Their combined current tallies are: 97 wins and nine titles.

I guess you win when you win, usually when you’re good and ready, and nearly always only when your stars align: right car, right team, right place.

Jochen Rindt, for instance, was the King of Formula 2 throughout a barren F1 spell that extended to 50 starts across almost five full seasons. His victory when finally it came, Watkins Glen 1969, was the foundation stone of his successful albeit ultimately tragic title bid of 1970. Friend and rival Stewart reckoned that the Austrian had at last learned how to win slowly.

Rindt’s victory also cost Motor Sport’s Denis Jenkinson his beard by way of a bet.

John Watson bet his beard on a first victory, too. When finally it came, Österreichring 1976, his 41st start, he wondered what all the fuzz had been about: driving a racing car had never seemed easier.

He wouldn’t win again until 1981.

If there is one thing that my numerical wade has taught me, however, it’s this: Richie Ginther was a superb number two.

Renowned as the best test driver of his generation, the little American registered 13 podium finishes in his first 36 GPs, with Ferrari and BRM. But when finally all his stars aligned 11 races later and he scored that first win, Mexico City 1965 – the first for Honda and Goodyear, too – the formula promptly changed from 1.5-litre to 3-litre.

Within two years he had dropped out and would soon be roaming the desert in a mobile home. You can’t blame him.

Had not Amon, another brilliant test driver – with zero wins from 96 starts – had the family farm in New Zealand to retire to, he probably would have done the same.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

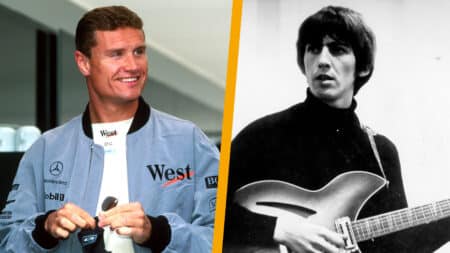

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song