However, on May 7, in other words after Imola but before Zolder, a rule clarification had been issued: “No ride-height-adjusting device should allow the car in its lowest position at any time to have a ground clearance of less than 6cm.” The result was widespread rule bending. The teams whose cars were equipped with hydropneumatic suspension quickly invented trick systems that enabled them to drop their cars to a ride height of much less than 6cm during running – thereby conferring ground effect – but in such a way that they would return to a ride height of the required 6cm by the time they had been brought to a stop for the scrutineers to inspect. Very clever but decidedly dodgy.

Reutemann did not like the feel of the new ersatz ground-effect F1 cars, but he nonetheless put his Williams FW07C on the pole at Zolder with a typically neat and fluent Friday-afternoon quali-lap of 1min 22.28sec, which was a gigantic 0.85sec faster than that of his closest challenger, Nelson Piquet, whose Brabham BT49C stopped the clocks after 1min 23.13sec had elapsed. It was a remarkable performance from Reutemann, not least because, in a practice session earlier that day, a 21-year-old Osella mechanic, Giovanni Amadeo, had slipped off the pit wall and had fallen between the wheels of his Williams as he drove along the Zolder pit lane, which in those days was the narrowest in F1. Carlos had had no time in which to brake and no room in which to swerve. Although no-one blamed him, and rightly not for he had been entirely innocent, he had been profoundly upset by the incident.

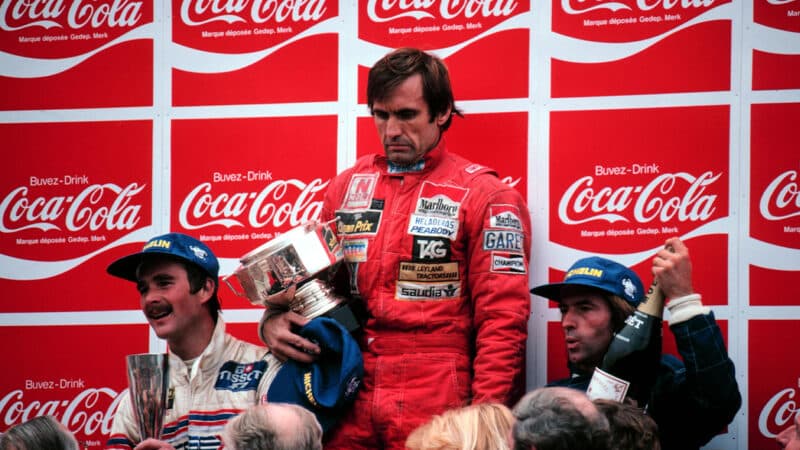

Unfortunate Reutemann was clearly affected by the pitlane accident

Amadeo had been knocked unconscious, having suffered a double skull fracture, and he was duly rushed to hospital, Universitair Ziekenhuis Leuven, 32 miles (51km) west of Zolder. He was resuscitated in the ambulance en route, and when he arrived in the hospital’s intensive care unit he was placed in an induced coma while the doctors tried their best to save him. However, he died on the Monday after the race.

The Ferrari and Renault teams had not been playing silly buggers with the regulations in the way that the British garagistes had, not least because their cars had the benefit of 1.5-litre turbocharged engines far more powerful than the ageing naturally aspirated 3.0-litre Cosworth V8s in the back of the Williamses, McLarens, Tyrrells et al. Didier Pironi qualified his Ferrari 126CK a fine third, while his team-mate Gilles Villeneuve ended up four places behind him in seventh. Alain Prost could manage only 12th in his Renault RE30 – but his team-mate René Arnoux failed to qualify.

However, that was not the worst thing that happened to Arnoux during the 1981 Belgian Grand Prix weekend. No, on Saturday evening, upset and angry about his DNQ, he drove out of the circuit in his company Renault 5 at full pelt, storming past all the queueing cars then snicking his way in at the head of the line, ready to drive out onto the main highway. In so doing, he attracted the ire of a marshal, who walked into the road in front of René’s Renault, held up his hand to stop him, then indicated that he should get out of the car. But Arnoux would not do as bidden, and, when the traffic light changed to green, he began to inch the car forwards in an effort to persuade the marshal to step aside. But the marshal was made of sterner stuff than that, and he climbed up onto the bonnet and sat on it, assuming that René would then stop and get out of the car as per his instructions.

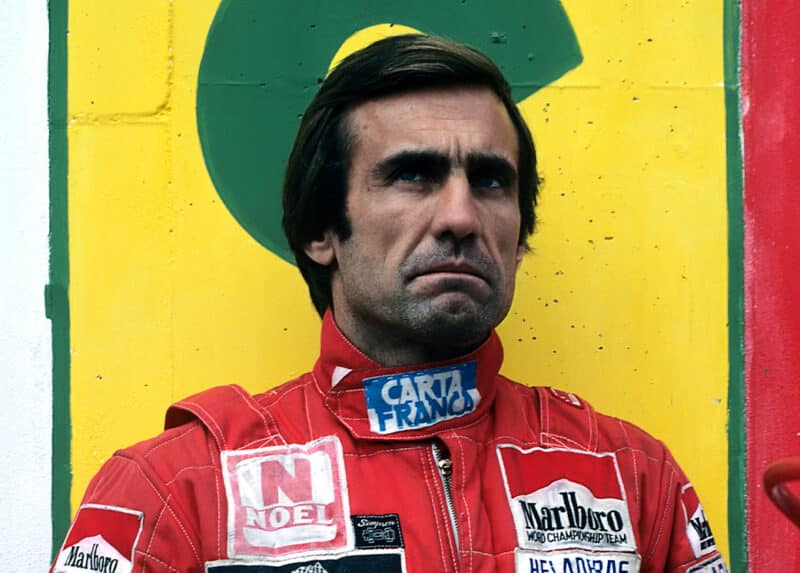

Laffite (left, in Austria) almost took the rap for the outrageous Arnoux (right)

Grand Prix Photo

But René did not do that. Instead, he drove to the hotel, a 10-minute journey that by all accounts he conducted at highly illegal speeds, while the hapless marshal clung onto the car by gripping its windscreen wipers until his knuckles turned white. When they arrived, Arnoux scarpered into the hotel and hid in the kitchen. Meanwhile the marshal called the police. When les flics arrived, they found Prost in the lobby and they asked him to take them to Monsieur Arnoux. For fun, Prost took them instead to Jacques Laffite, introducing the astonished Ligier veteran to them as Monsieur Arnoux. In the end the police found and arrested René, and he spent a night in the cells. F1 was a bit different 44 years ago. There was more tragedy, certainly – and more’s the pity for that – but there was more comedy, too.

On race day, the mechanics from all the teams staged a protest on the basis that one of their number was fighting for his life in hospital as a result of the wholly unsatisfactory safety levels of the reprehensibly narrow Zolder pitlane. They had a point, and they were joined in their protest by four drivers: Pironi, Villeneuve, Prost, and Laffite. However, ignoring all the mechanics’ and four of the drivers’ protests, the organisers flagged off the formation lap at the agreed time, despite the fact that Pironi, Villeneuve, Prost, and Laffite were not yet in their cars.