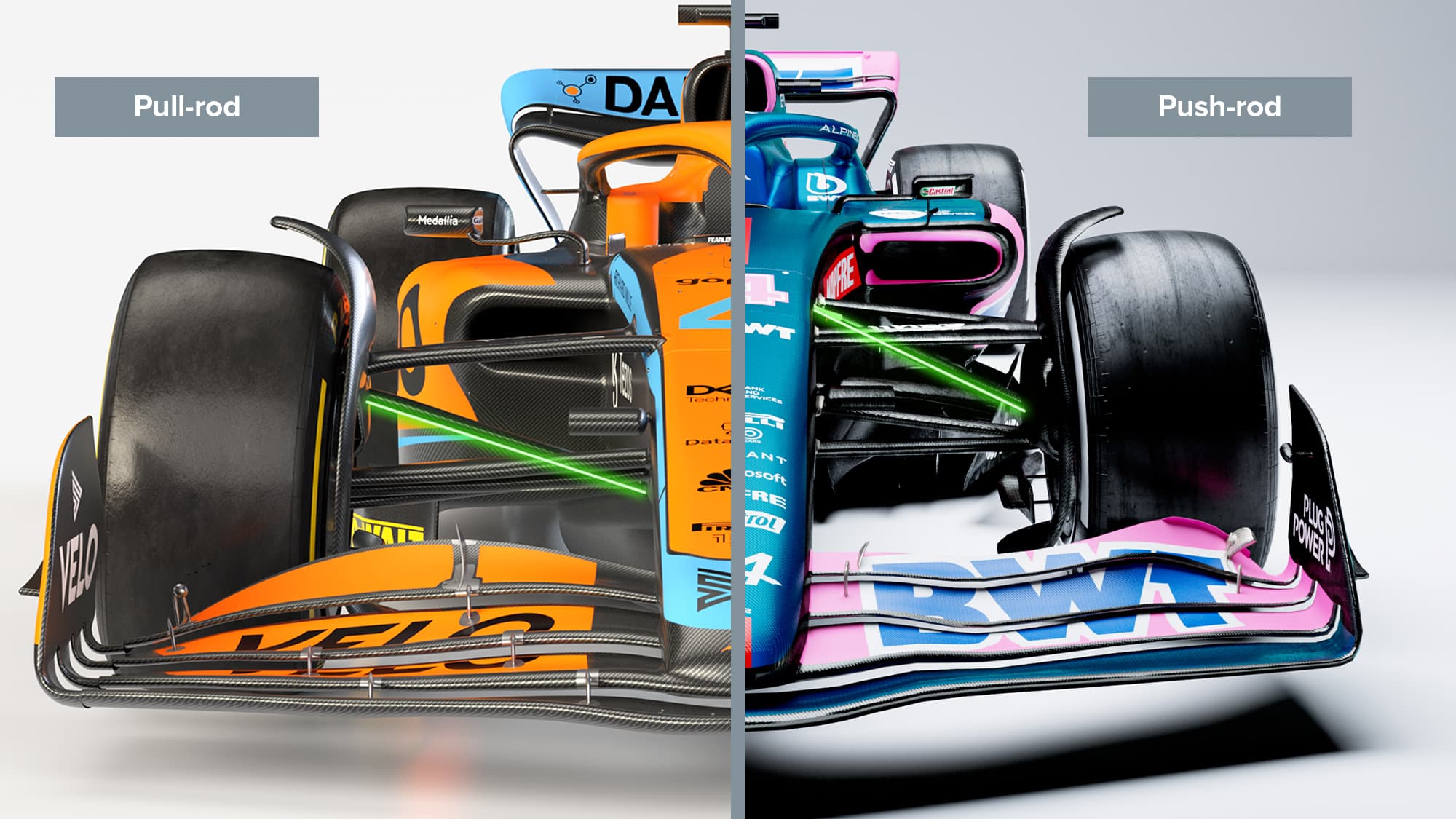

McLaren and Red Bull place pull-rod suspension gamble for 2022 F1 cars

Pull-rod suspension is back in F1 for the first time in 2015, but can McLaren and Red Bull ensure the benefits outweigh the problems?

Flo vis paint clearly shows McLaren's pull-rod suspension and long-chord wishbones

Rudy Carezzevoli/Getty

Formula 1’s new regulations have seen the revival of past concepts: as well as the return of ground effect from the 1980s, there is also pull-rod front suspension, from a little more recently in history.

Both McLaren and Red Bull (when they finally showed us the real RB18), have opted to run this suspension system, something that hasn’t been seen in F1 since 2015 and the Ferrari SF-15T.

It is Red Bull’s interpretation that has drawn the most attention, which features slim elements in contrast to the trend across the rest of the field towards long-chord wishbones (wide when viewed from above). The upper wishbone is also angled steeply backwards and its rear mounting sits much lower than the front. However, slightly overlooked has been McLaren’s use of a push-rod setup at the rear, reversing a trend to use pull-rods over the last decade (started by Adrian Newey on the RB5 in 2009).

To clarify what these terms means, the front suspension of a current F1 car is made up of upper and lower wishbones, with rods connecting the upright to a rocker, which actuate the suspension springs and dampers. In the case of F1, the spring is a torsion bar which runs fore and aft along the chassis, located on a spline in the centre of the rocker. This is what is commonly known as an inboard suspension setup, as opposed to the outboard mounting of the spring/damper units, as you might find on a road car.

Slim elements for Red Bull’s pull-rod setup

ANP via Getty Images

Inboard suspension first started to appear in F1 thanks to Colin Chapman and the Lotus 21 in the early 60s and by the end of the decade, it was de rigueur. These first systems were push-rod operated, but in the 1970s Gordon Murray, then at Brabham, came up with a pull-rod design. Over the years, the popularity of pull rods has waxed and waned depending on how favourable the technical regulations have been to their implementation.

Simply speaking, a push-rod system places the rocker at the top of the chassis, with a rod attaching it to the upright which pushes the rocker as the suspension compresses. A pull-rod works the opposite way round, the rocker affixed to the bottom of the chassis, with a rod pulling it as the suspension compresses. There are benefits and disadvantages to both systems, but in the context of modern F1 cars, the general consensus since 2015 has settled on push-rod front and pull-rod rear.

This previously universal approach was driven by aerodynamics and packaging, and the former is no doubt the reason Red Bull and McLaren have opted for the approaches they have. The position of the front suspension components, sat as they are directly in the airflow coming off the front wing, means they have a considerable influence on that air as it heads towards the centre and sides of the cars. Adjusting the position and shape of them can help move the air where it is most wanted (in as controlled a manner as possible), which is now into the underfloor tunnels.

Theoretically, there are benefits to mounting the springs and dampers on the underside of the chassis, allowing the nose to be higher and thus giving a less obstructed path for air to the underfloor. The inclination of the push/pull rods will also likely have an effect on how much air is moved outboard from the front wing and how much is kept inboard.

However, mechanically speaking, it is harder to make a pull-rod work in an optimal way when packaged in the tight confines of an F1 car’s nose, to the detriment of mechanical grip. Clearly, both McLaren and Red Bull have decided that the benefits outweigh the problems, at least so far as their overall aero concepts are concerned, safe in the knowledge that time and budget cap constraints mean no one is likely to copy their approach this year.