In the late 1950s the factory Norton team acquired its first title sponsor Slazenger, at that time an upmarket clothing brand known for its tennis and cricket kit and associated fashionwear. The marketing arc was obvious: Wimbledon, Lords and Brands Hatch.

It is pretty much impossible to imagine such a brand becoming a title sponsor of a motorcycle-racing team today. And who would mention bike racing at Brands in the same breath as tennis at Wimbledon and cricket at Lords?

That’s because the summer of 1964 turned Britain’s monied classes off motorcycles, which were now dirty, oily symbols of rebellion, beloved of delinquent, long-haired youths.

Thus upmarket businesses had no desire to invest motorcycle racing, which struggled to attract sponsors and became a mostly working-class pursuit.

Since 1964 Britain’s greatest racers have come from working-class backgrounds: Bill Ivy, Barry Sheene, Ron Haslam, Carl Fogarty and the country’s most recent MotoGP winner Cal Crutchlow (whose dad was a rocker). Nothing at all wrong in that but it shows that the monied classes – and the money with them – abandoned motorcycle racing.

Mods and Rockers were a turning point in British motorcycling, but that point had already been passed in the USA.

The 1953 US release of The Wild One (banned in UK cinemas until the late 1960s) had the same effect on the American public mood as Mods and Rockers had in Britain.

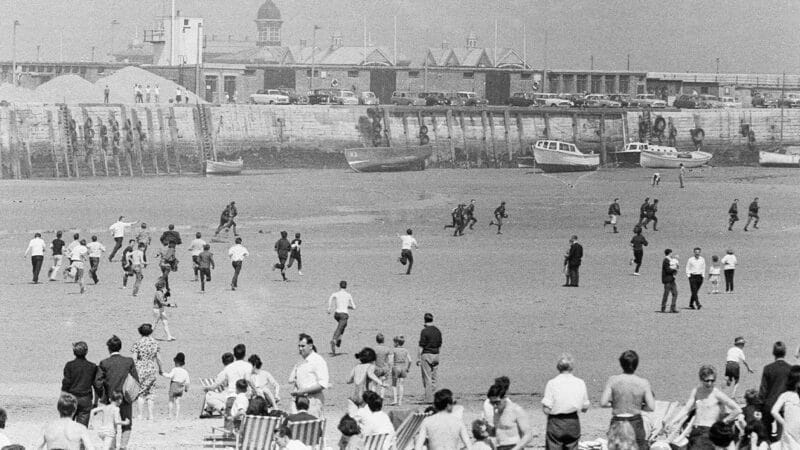

Mods pursuing Rockers on Margate beach, watched by holidaymakers, May 1964. Hardly the end of Britain as we knew it

Mirrorpix/Getty Images

The iconic movie, starring Marlon Brando, told the story of several wild motorcycle gangs – The Pissed Off Bastards, Boozefighters and Market Street Commandos – that trashed the Californian town of Hollister in 1947.

Biker gangs were a growing phenomenon in the States following the Second World War. Demobbed soldiers bought ex-military Harley-Davidsons and Indians for a few dollars, rode together and drank together, often at the same time. Charging around the country in gangs was probably their way of dealing with PTSD (although they didn’t know it).

The Hells Angels (sic) is the most famous biker gang of them all, named after a B-17 Flying Fortress which flew bomber missions in WW2. The Angels was founded by a soldier who had split from the Pissed Off Bastards, established in 1945.