MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Meeke got away with it in Mexico, which is more than can be said for some. Motor sport’s late gaffes…

It used to be in gravel rallying that to finish first, first you had to be Finnish. Such is the sport’s cosmopolitan make-up today, however, that a Belgian and a Frenchman were awaiting the (probably) victorious arrival of a Northern Irishman at the end of the Power Stage in Mexico.

Less than a kilometre up the road Kris Meeke was enduring the fright of his life – and no doubt saw his WRC future flash before his eyes – as he skimmed past and then auto-tested around several parked spectators’ cars before regaining the stage through a gap in the brush.

He somehow hung on to score the win that should open the next chapter of a career that his abundant talent and undeniable tenacity warrant, but before he celebrated it he sat red-faced in the Citroën reflecting on how a fractional error – too sideways over a compression in the road – had almost slammed the book shut.

Only he knows why he was pushing so hard with 37 seconds in hand and just 13.7 miles to go. Perhaps he wanted to maintain the rhythm born of confidence that had seen him dominate the event. Or perhaps it was the lure of five points for fastest time, a two-point increase from 2016.

But we all know how lucky he was. Though there was skill to be admired in his escape to victory, too.

Coping with pressure is the fundamental task facing all professional sportsmen. It’s what separates the great from the good. But even the great can goof with victory within their normally iron grasp. It’s what makes them human.

Sébastien Ogier, whose second place/almost first in Mexico is apparently under threat pending a ruling on his Ford’s gearbox, infamously wedged a VW Polo into Armco on the final stage of the 2015 Catalonia Rally. The differences between this and Meeke’s Mexican sand-off were: when the VW shed a wheel it was “game over”; and that the man from Gap had long ago secured his third consecutive world title.

Ogier admitted that he was pushing hard to enliven what had for him been a dull event – even though he was leading by 50 seconds – and that not much damage, beyond the mechanical and cosmetic, had been done.

At the other end of the scale was François Delecour’s 1991 Monte Carlo Rally experience.

On his first event in a 4WD works car – a Ford Sierra Cosworth 4×4 – and having made his name with outstanding performances in a small fwd machinery without yet winning a rally of any kind, the man from Lille astounded expectation in typically mixed conditions, pronouncing accurately which stages he would win and on which he would lose time.

On SS24 (of 27) he wrested the lead from the Toyota Celica of Carlos Sainz and, with a stunning time on the penultimate test, Col de la Madone, forced even ‘El Matador’ to concede to unexpected defeat.

On the ascent of Col de Turini, however, the Q8-backed Ford suffered rear suspension failure. Although a tearful Delecour – until that moment he had kept his emotions impressively in check – insisted that he had not hit anything and his compatriots believed him – the French love a gallant loser – opinion in the wider community suggested that perhaps he had: a bridge parapet, a verge or a snow bank.

There was something about his wild-eyed obsession that rang alarm bells for some.

Instantly listed as rallying’s most exciting talent, Delecour’s career didn’t flower as it ought. He won thrice in 1993, including a mixed-surface victory in Portugal – he had by then and much to his chagrin been labelled a Tarmac specialist – and started 1994 as one of the title favourites. But, having won the Monte in a Ford Escort RS Cosworth, he suffered leg injuries in a road accident while at the wheel of a friend’s Ferrari F40.

Vital momentum had been lost and would never be recovered fully.

Rallying, of course, is, despite recces, pace notes and gravel crews, a fund of the unexpected. Motor racing is more contained and repetitive and more predictable as result – unless you happen to have one, two or even three F1 world championships to your name.

Alberto Ascari, arguably the category’s greatest frontrunner, had won 11 of the previous 13 world championship rounds prior to the 1953 Italian GP at Monza. (It would have been 12 had not his Ferrari shed a wheel while he was gaining 10 seconds per lap to comfortably lead the German GP at the Nürburgring.)

Monza without chicanes provided its usual frantic slipstreamer, which boiled down to the final corner of 80 laps.

According to the book Fangio by Fangio – ghosted by his confidant Marcello Giambertone, the man himself would later distance himself from it – Ascari made an error: “As he came out of the bend, there in front of him was a slower car which we had all passed several times. All Ascari could do was to slam on his brakes, throwing his car across the track.”

Other reports had the newly crowned double world champion spinning on oil.

What happened next is beyond doubt.

Fangio continued: “… [Onofre] Marimón was coming up like a cannonball. I was less than three feet away when I heard the metallic crash of the collision. [Ferrari’s Giuseppe] Farina courageously drove off the track to avoid hitting them.

“I gripped the wheel, desperately steering to my right on the inside of the corner… I still do not know how I found my way through that mess as Ascari’s spin threw up a cloud of dust.”

Ascari’s mood was not improved by the fact that Marimón was five laps in arrears after a long stop to repair the oil radiator. The Argentinean had been in the mix prior to that, however, and thereafter determined to help his friend, mentor and team-mate Fangio score the first world championship GP victory for Maserati.

Jack Brabham had three F1 titles behind him when, on a tight, defensive line dusted with cement, he missed his braking point at Monaco’s Gasworks Hairpin in 1970.

A combination of “the most shocking run of slow back markers of my entire career” and the looming Lotus presence of an inspired Jochen Rindt – Colin Chapman’s “war dance’ also caught Jack’s eye as he entered the last lap – had caused the field’s most experienced man, one of its most reliable top men, “to drop it”.

And Sebastian Vettel had just one of four titles with Red Bull Racing under his belt when McLaren’s Jenson Button completed F1’s greatest turnaround – he was dead last after 37 (of 70) laps – by pressuring the German into a late, late mistake in the Montreal wet to win the 2011 Canadian GP, a rally masquerading as a four-hour race.

Even the toughest, fiercest competitors have exhibited meekness on memorable occasions. You’re in good company, Kris.

But, I humbly beg, on behalf of we normal human beings – simple fans inclined to be shocked easily and slow to recover our equilibrium – please don’t do it again

Parking can be so stressful.

PS Thanks to Ogier and Sébastien Loeb, with WRC 117 wins between them, those gallant French losers have surpassed the flying Finns: 184 plays 177.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

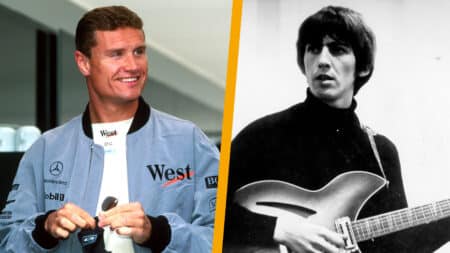

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song