MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Paddy Lowe has quietly racked up more than 150 victories in Formula 1, Paul Fearnley looks at Lowe’s influence

Nico Rosberg’s victory at Spa-Francorchamps in August marked the 150th win of Paddy Lowe’s Formula 1 career.

It’s helped that he’s worked for heavy hitters Williams, McLaren and Mercedes since his arrival in 1987 – but the best jockeys get the best horses.

Or rather in his case the best trainers school the best horses.

This engineering graduate of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, was effective straight out of the box: Metal Box, that is.

“A British packaging company that no longer exists,” explains Nairobi-born Lowe. “I was a control engineer doing systems for its machinery.

“It was a help [in Formula 1] actually. It seems pretty distant but, like many industries, packaging is more technical than you might think. The margins on a tin can are minute and so an awful lot is invested to make better cans for less money.

“I watched a TV programme about it recently.”

Has canning moved on since the early 1980s?

“Not particularly, no,” laughs Lowe. “There must have been improvements, but they were too subtle to notice.”

The same cannot be said of the F1 of the past 30 years: an era of advancing technology versus increasingly rigorous rules.

The dominant 1992 Williams team, Lowe’s final year with the team

Lowe’s career began when the balance was tipped in the former’s favour, when many areas of performance gain had yet to be considered let alone codified.

His first task was the perfecting of Williams’ version of active suspension.

“I joined in October/November 1987 as joint head of electronics,” he says. “An engineer called Steve Wise [still with Williams] and I started on the same day and were charged with setting up a new department.

“Williams at that time had no internal capability for building electronic control systems.

“Steve was biased towards hardware and I was biased towards software, so we were a great combination.

“Frank Dernie employed us and he was my boss until he moved to Team Lotus [for 1989].

“He was actually looking for a technician but, having interviewed Steve and myself, realised that he needed engineers – and that the team had bitten off a bit more than it could chew.”

Although Williams’ reactive system – Lotus had gotten very protective about its more complex active suspension – had already won in Nelson Piquet’s hands at Monza in 1987, problems were stacking up.

And that’s before Honda took its turbo power to McLaren for Ayrton Senna in 1988.

Lowe: “The background was that Williams had started racing a system very much as an R&D exercise and was using an external contractor – Kurt Borman – for the electronics: the onboard computer and the software.

“What began to unravel at that exact point was that the team was unprepared for the complexities of running a control system like that on a race car.

“We were competing in early 1988 using a system not fit for purpose.

“Over the next three/four years Steve and I created a computer fit for purpose. We built the capability to: design harnesses fit for purpose; design and fit instrumentation, control valves; and devise software for the onboard computer, software for the system that talked to that computer, and software for the data-analysis.

“We created a department to deliver such systems and race them reliably, and support them; to have information available for race engineers and drivers to work with.

“We took it one year at a time: building the infrastructure, employing the people, designing the computers.

“I was the project leader of active suspension and Steve was the project manager of the semi-automatic gearbox control.

“In terms of active we ran for several years with a car that was a year out of the date, by way of an R&D programme. We had our own car, our own driver – Mark Blundell [and later Damon Hill] – our own truck and our own team.

“Mainly we went to Pembrey [in South Wales].

“I liked going there. A nice little track, it had all the elements we needed in terms of types of corner and so on.

“Eventually we got to a point in 1991 where we converged: a current car fitted with active so that we could do a direct comparison.”

“We were sure it would work. But many weren’t.”

Lowe crouched next to Sir Frank Williams in 1992

Nigel Mansell, a naysayer because of his problems with earlier iterations at Lotus (in 1983), as well as at Williams, ran the system for a few practice laps at the season’s Adelaide finale.

“The car was still too heavy,” says Lowe.

“The trouble with R&D is that you are always using spare resource to some degree. You are on the back foot trying to grab and borrow bits and time and effort from people.

“And if you don’t know absolutely that it’s going to deliver, you don’t put in a huge commitment in case it puts your main programme at risk.

“Patrick [Head] was very supportive after Frank [Dernie], the project’s initiator and champion, left. He picked up the baton and provided the resources to keep going.

“He kept the faith.”

Lowe’s active-suspension FW14B was unmatched

Head gave the green light after a week’s winter test at Estoril – just six weeks before the start of the 1992 season.

Lowe: “The system was massively more complicated than 1988’s – though if you laid it out on bench you would think it simpler; it was far more elegant.

“In terms of software it did far more.

“1988’s stuck at a constant ride height at all speeds, which is the essential part of having reactive suspension for aerodynamic benefit.

“What we were doing in 1992 was scheduling ride height in quite a complex manner. It didn’t anticipate – but you could feed-forward.

“One of the big gains we found was tipping the car in as the driver turned the wheel; it banked itself.

“One of the nice things about 1992 was that a lot of things came together all at once. We got the gearbox, which had been a bit ropey in 1991, sorted out – and we invented traction control, which was worth another second per lap, for far less work by the way than active suspension.

“When we went to Kyalami [for the opening round] we brought all these systems: worth two seconds a lap, plus another half from the gearbox relative to McLaren’s.

“I kept waiting for McLaren to turn the wick up. But eventually I realised that we had something that they couldn’t match.

“It was very interesting to watch the Senna film because I had never seen it from his point of view. He was the enemy. We had put years of our lives into inventing new systems to try to beat him.

“In the film you saw the other side: how depressed he was. He realised that they had been caught napping.”

Lowe added 83 wins with McLaren

McLaren threw the kitchen sink at it, brought its new model forward by a month – and sent six cars to Interlagos – but Mansell and FW14B were unstoppable by then, winning the first five of six GPs – and nine in total.

By the time McLaren’s active car finally arrived, at Monza in September, ‘Our Nige’ had wrapped up the title.

And rising star Lowe was on the verge of being poached.

After 21 wins with Williams he joined McLaren, where he worked his way through the ranks while being involved in 83 further victories between 1993 and 2012.

And after a spell of gardening leave he joined Mercedes-Benz in June 2013 as executive director (technical) – whereupon Rosberg promptly won the British GP.

Just sayin’.

Lewis Hamilton’s most recent victory in Mexico was the 51st of his career.

It was also Lowe’s 51st with Mercedes-Benz.

And he now has as many wins as the Cosworth DFV: 155.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

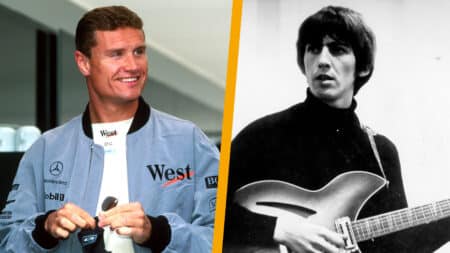

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song