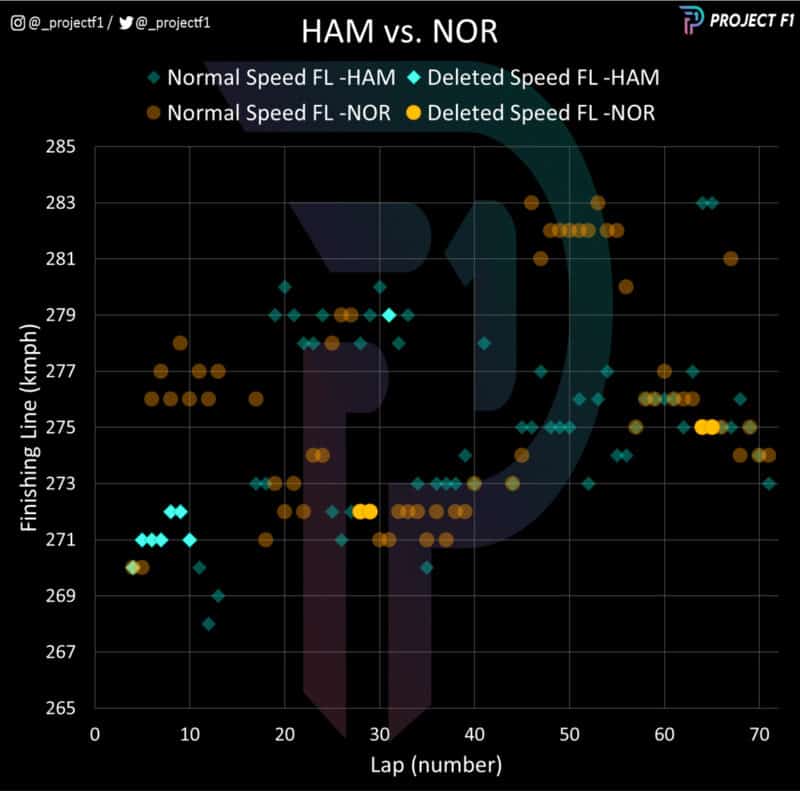

It was clear that, at the end of the Red Bull Ring lap, the wider drivers went in Turns 9 and 10, the faster they would be on the pit straight. In a simplified version of their judgement call, drivers could take a cautious approach, leaving plenty of their car on track and avoid the risk of a penalty, or try and judge it to the millimetre, keeping just the required two tyres on the asphalt and gaining valuable time, but with no margin for error.

Making that decision trickier was the difficulty in seeing the white line from the cockpit and the cars’ tendency to drift to the outside.

Some indication of the best route to follow comes in the fact that the top five finishers managed to find a happy medium, running at the front without receiving any penalties.

But did pushing the limit pay off for any driver? And how much did they stand to gain from an aggressive approach?

The cost of breaching track limits in qualifying

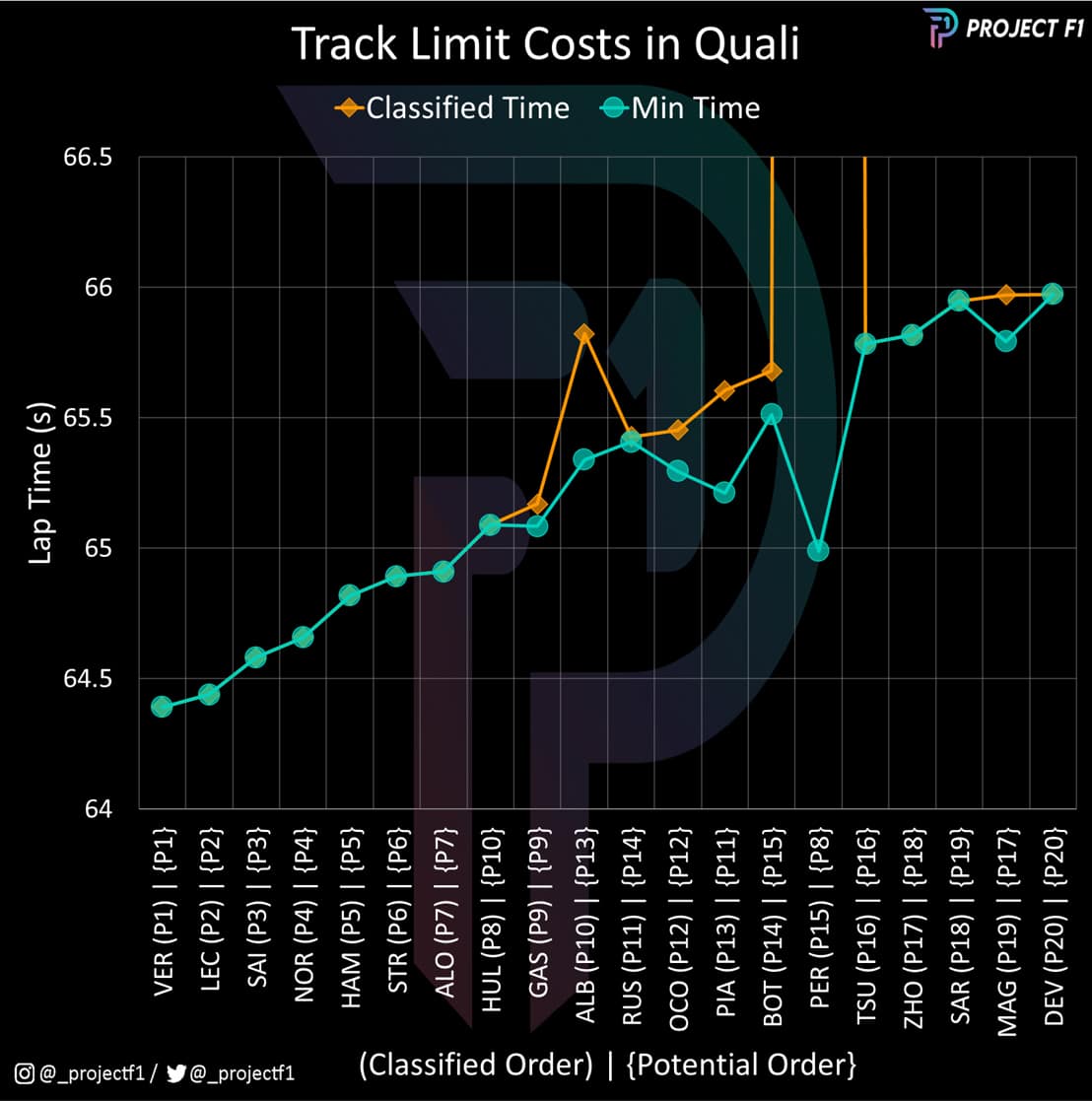

Chart 1 Classified vs fastest times per driver

The first chart plots the fastest lap time set by each driver in qualifying, irrespective of whether the lap was deleted, and — in orange — their qualifying time. The lines diverge where a lap time has been ruled out for exceeding track limits.

Drivers with deleted laps did go faster when they went out of the white lines (mostly at Turns 9 or 10), although taking a wider line may not be the sole reason — subsequent lap times may have been affected by a more cautious approach or tyre degradation.

However, the time gained on the deleted laps doesn’t appear to have been worth the risk for many drivers. If we reinstate all deleted laps, Pierre Gasly would still have started ninth and Esteban Ocon would still be 12th. Most drivers would have only gained or lost one or two places. Sergio Perez clearly lost out by pushing his car to the edge of the circuit: his fastest time would have seen him starting eighth, rather than 15th after failing to complete a competitive lap in Q2.

The time gains available by exceeding track limits

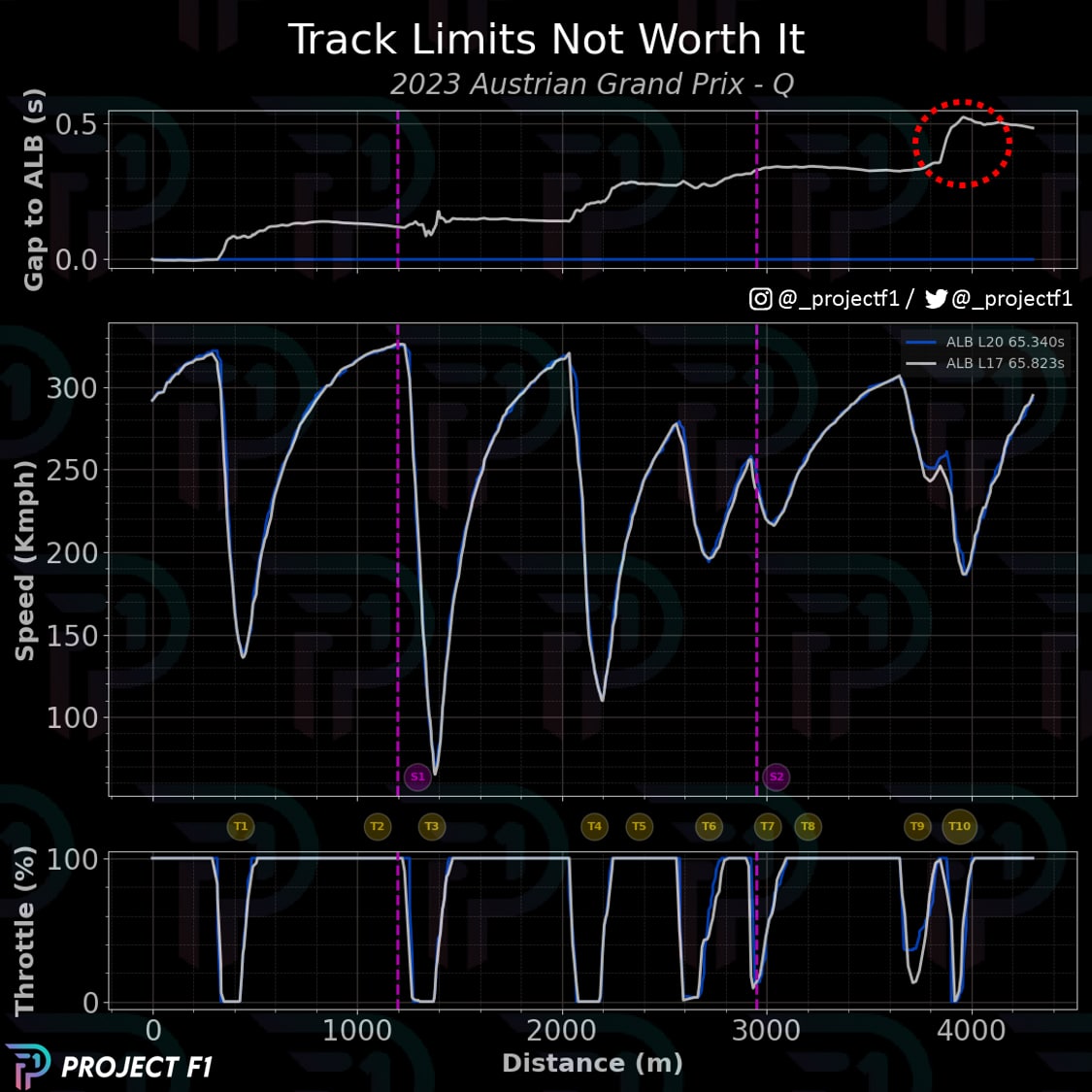

Chart 2 – Alex Albon lap comparison

It is clear that there was significant time to gain by running wide through the final corners and having a better run onto the start/finish straight. Chart 2 illustrates this by comparing telemetry from two of Alex Albon‘s qualifying laps: the legitimate lap 17 and the deleted lap 20, which was almost half a second quicker. It’s a huge advantage in qualifying, and the reason that we’ve picked this example.

The gain through Turns 9 and 10 is notable (it is the single largest gain across the whole lap), but skirting the edges of the track is a risk that doesn’t pay off and the lap is deleted.

It wasn’t just a question of gaining time through the final section, however. Had Albon taken exactly the same approach as his previous attempt, he would have still bested his laptime by about 3-4 tenths. The overextension through the final complex of corners threw away the gains across the whole lap.

The closely-fought race

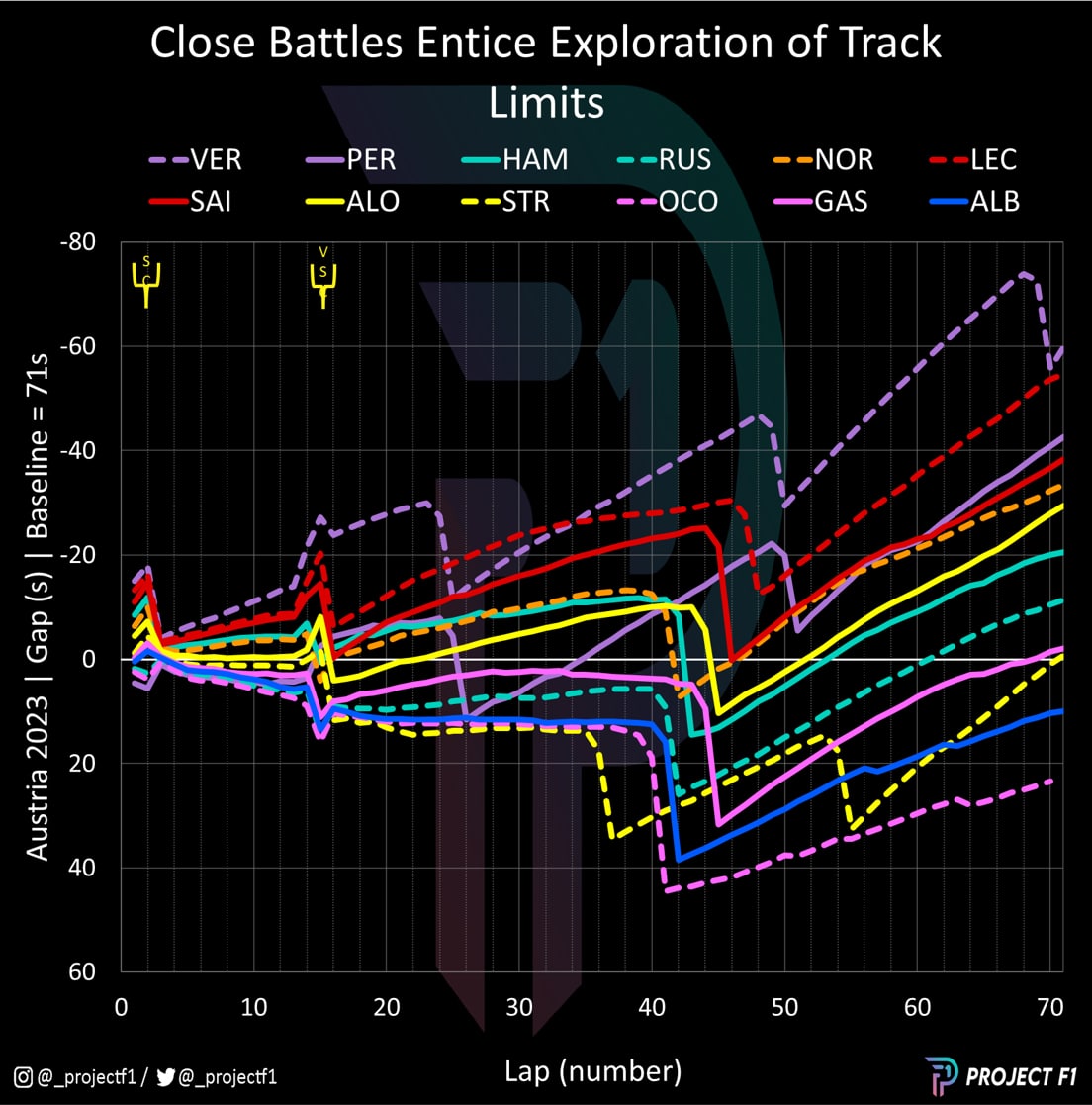

Chart 3 Cumulative delta plot

It’s natural for qualifying to feature a few track limit penalties, when drivers are giving it their all for a single flying lap. But they are usually less of an issue in the race, let alone the 1200+ infractions recorded at the Red Bull Ring.

Given the multiple warnings before penalties are handed out, what was going on?

The push to flirt with track limits during qualifying is generally down to the pursuit of peak performance. During a grand prix, individual laps may be less critical, but drivers are still straining for every advantage in the heat of battle — then there’s race strategy, tyre wear, fuel burn, DRS and more to consider.

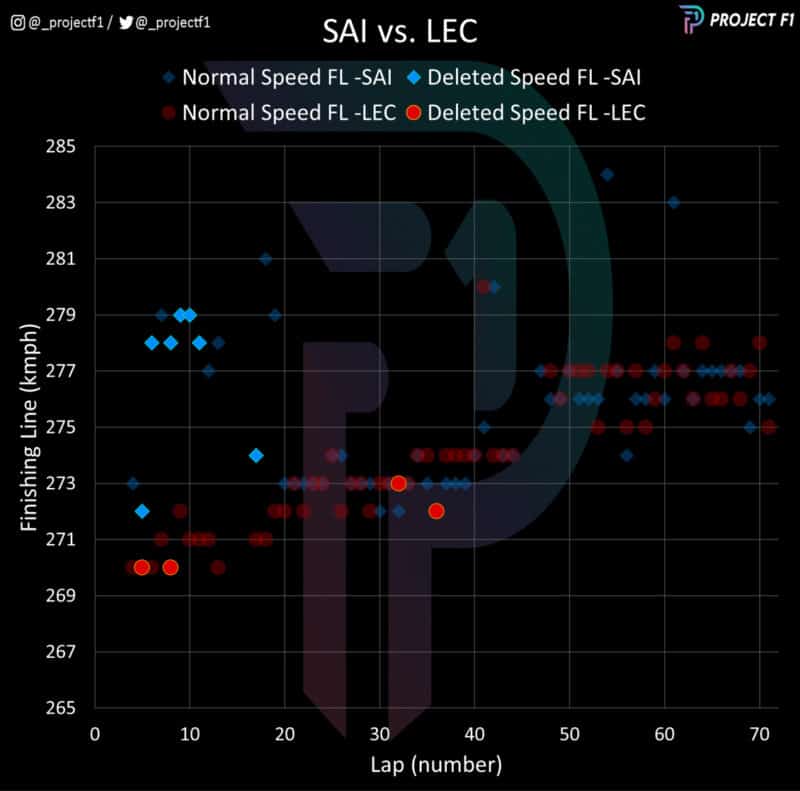

In isolation, it’s difficult to see why it’s worth the risk of a 5sec or 10sec penalty by skirting the edge of the track just for an extra few tenths on the pit straight, but if it appears to be the difference between retaining or conceding a position then it becomes a lot clearer.

Chart 3 shows the cumulative delta for the race, plotting each driver’s average lap time, updated for every lap of the race, and set against an average 1min 11sec lap time.

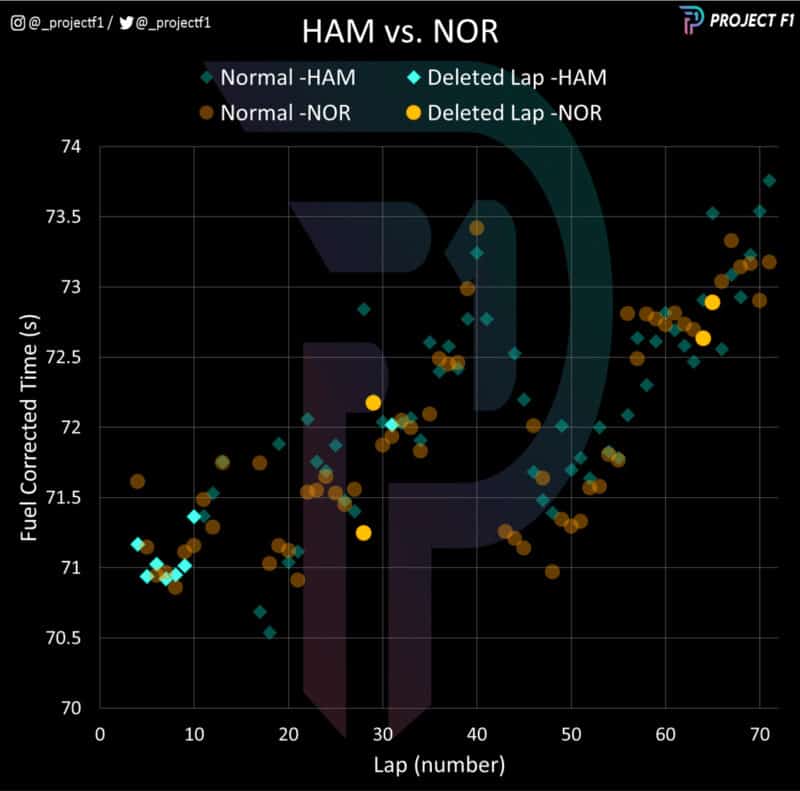

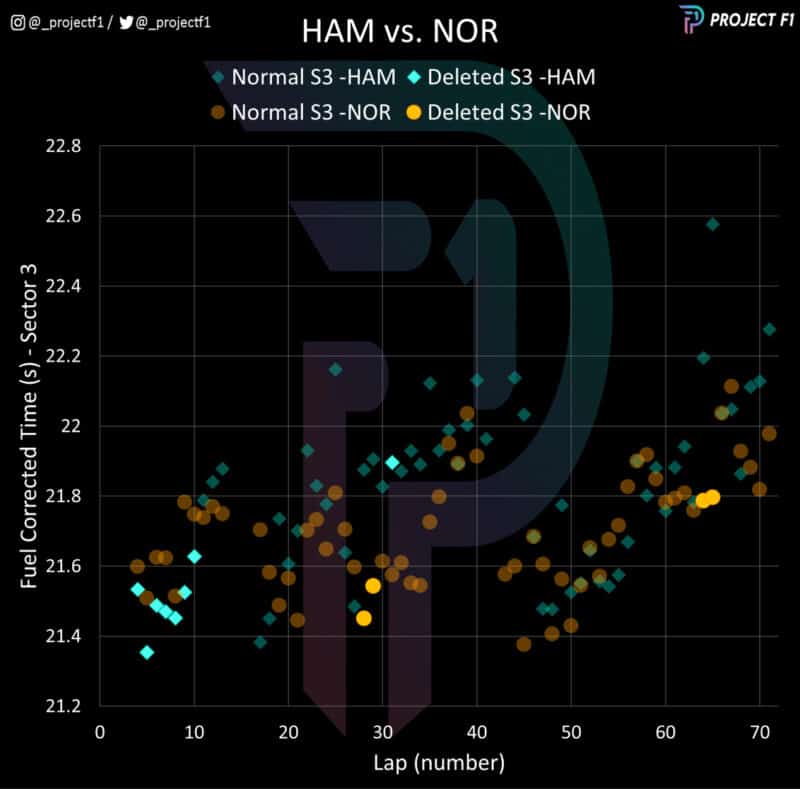

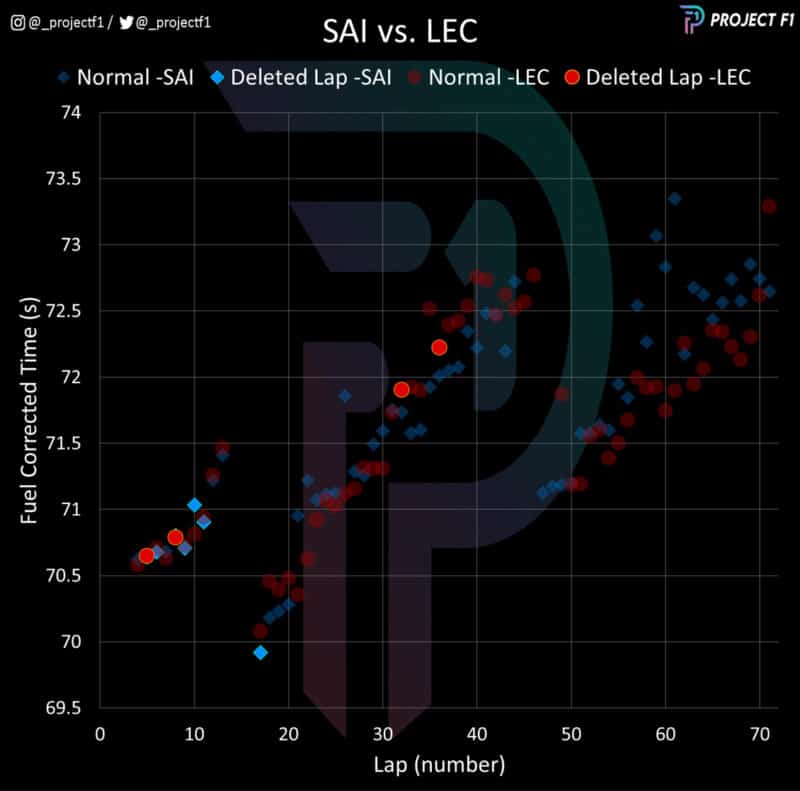

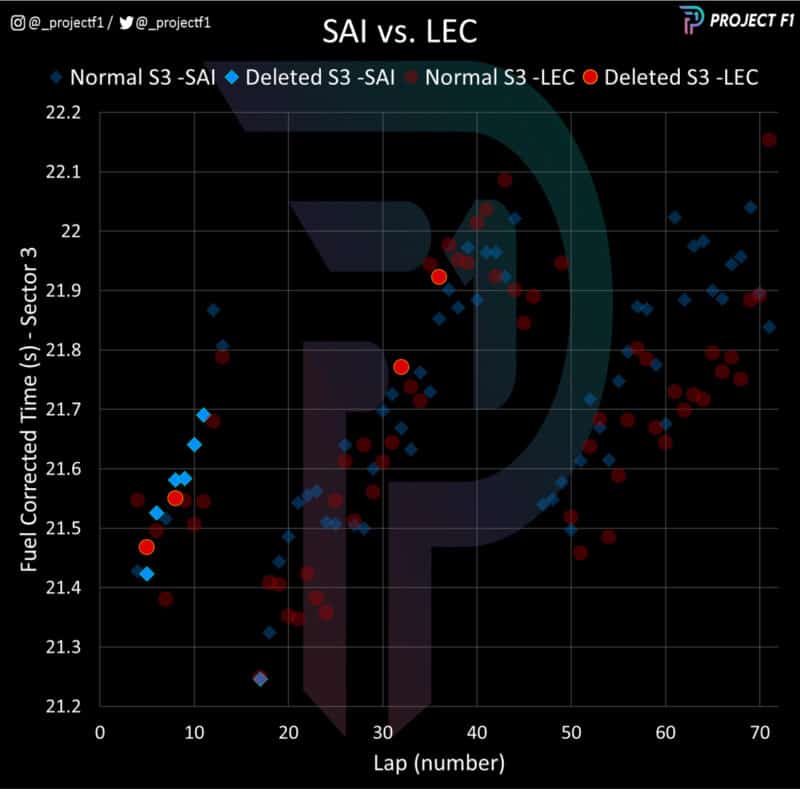

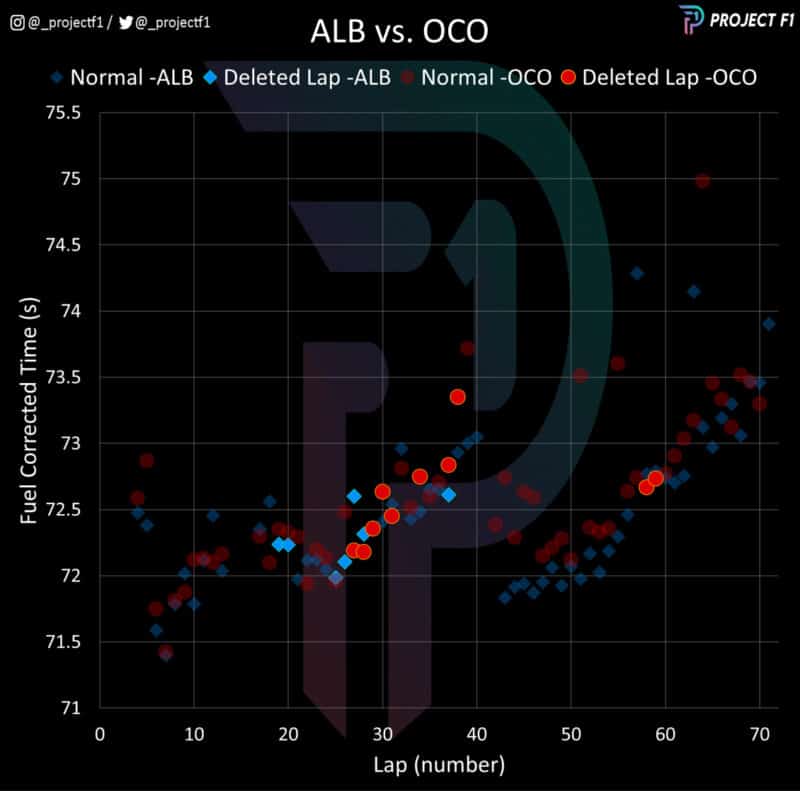

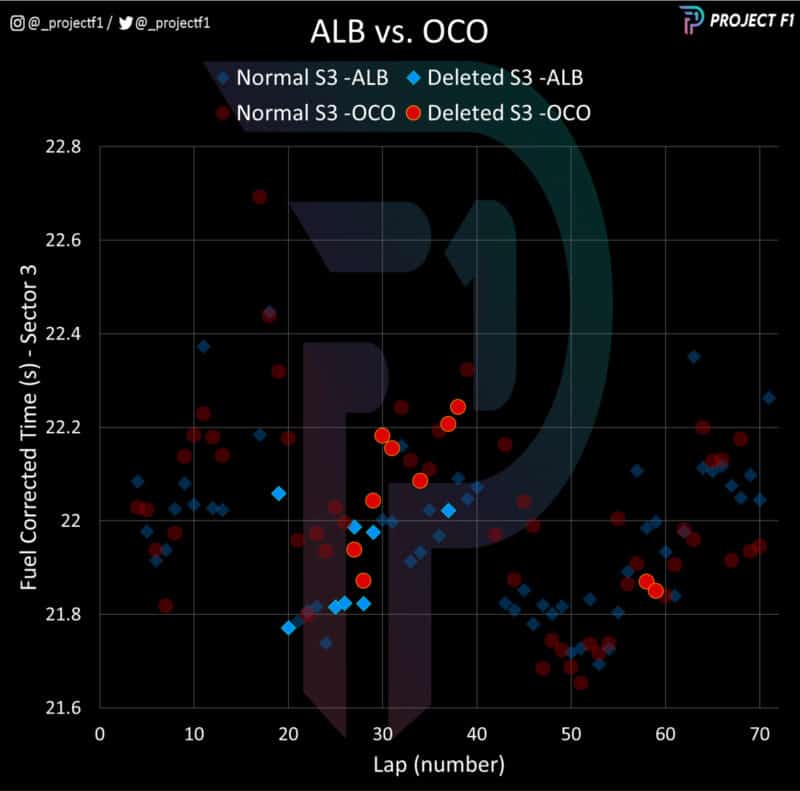

The closeness of the lines reflect the tight nature of the race: those of Lewis Hamilton and Lando Norris, Charles Leclerc and Carlos Sainz, as well as Albon and Ocon almost converge at points, showing the intense competition.

By taking a closer look at these battles, with a focus on the impact of Turns 9 and 10, we can begin to understand why drivers pushed limits to such an extreme.