MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Dick Seaman’s career, surrounded by the swelling foundations of Nazi Germany, was epitomised by chaos and conflict 80 years ago

Can there have been a racing driver more conflicted than Richard John Beattie Seaman was at the 1938 German Grand Prix?

His life must have flashed before him when the Mercedes-Benz W154 of team-mate Manfred von Brauchitsch burst into flame during its final scheduled stop.

Suddenly the choreographed order that he had so craved – in a letter Seaman likened the mechanics to a PT squad at the Royal Tournament – descended into chaos as men in white overalls dashed for fire extinguishers, and their lives.

But it was not shock that broke across Seaman’s face, rather, bewilderment, followed by realisation: I can win.

Car wheeled back, he nudged through the milling throng – smoke and foam onto the concrete apron – and accelerated away.

He did not, as legend suggests, await instruction from team manager Alfred Neubauer – whose wave of his flag was understandably distracted, half-hearted and retrospective – and only 5-10sec had been lost.

The most politically charged GP victory lay six laps’ distant.

It had been a difficult second season for Seaman with Daimler-Benz AG.

His first had been busy as he learned the trade in its hugely powerful W125 of 1937 and he impressed team members with not only his calm collection and skill but also his focus and engineering grasp.

They liked him. And he liked them.

But that was no longer enough by 1938.

Hitler’s boastful aggrandisement was gathering insidious pace, force and volume and the presence of an Englishman in Germany’s most high-profile sporting team – how else was he expected to win, the poor fellow? – was propaganda enough without risking him having actually win something.

Home-grown heroes von Brauchitsch, Rudolf Caracciola and Hermann Lang were clearly ahead in the pecking order.

There were other reasons for the slow start to Seaman’s 1938.

A radical change of formula had put even the mighty Mercedes-Benz on the logistical back foot: just two of its new 3-litre V12s were ready for Caracciola and Lang in time for April’s Pau GP.

That they were beaten sensationally by a stripped-down Delahaye V12 sports car driven by René Dreyfus suggests that they weren’t entirely prepared at that.

Four were sent to May’s Tripoli GP but the team was limited to an entry of three. When its proposal that the remainder be run in British Racing Green – which would have been something given the nationalistic machinations – was rejected, Seaman was benched.

Jealous French officials capped Mercedes-Benz at three also for its GP de l’ACF at Reims in June. Seaman was fastest during Friday practice but did not race.

The dam burst at the Nürburgring in late July: seven W154s – four race cars and three T-cars – were presented and Seaman was given his head while newcomer Walter Baümer was this time held in reserve.

Seaman chipped off the rust while qualifying third – albeit a second per mile slower than the aggressive von Brauchitsch – and lined up on the outside of the front row.

His Nazi salute, when it came, sagged somewhat from the elbow

He was ahead of Caracciola, who was suffering from a stomach complaint, and Tazio Nuvolari, who was contesting his first race as a contracted Auto Union driver in its brand-new D-type.

The start was ragged and Lang led by 9sec at the end of the first lap. Seaman reduced that to 6sec next time around but von Brauchitsch was catching them both.

Lang pitted because of a fouled plug after three laps and von Brauchitsch took the lead: the perfect Nazi script, for aristocratic Manfred was nephew to Hitler’s recently appointed Commander-in-chief.

Seaman, sufficiently ambitious to risk and eventually wreck his disapproving family’s dynamic but a team player nevertheless, knew his place.

Not that von Brauchitsch was convinced: at his first stop he complained to Neubauer about the Englishman’s unnerving ‘steady’ presence that had included his setting the race’s fastest lap.

Poor Neubauer was also copping it in the ear from Nazi officials blaming oil dropped by a Mercedes-Benz for Nuvolari’s damaging spin on the opening lap.

The 350,000 spectators were not to know it but the 22 laps – more than 500km – through echoing Wagnerian forest comprised half, perhaps less, of the battle being enacted.

Von Brauchitsch has been stationary for 15sec – long enough to fit new rear Continentals as well as to slug in 80 gallons of exotic brew – when Seaman rolled in; easier on his rubber, he was considering fuel only at this his second stop.

So it was going to be close – and a mechanic became careless in his understandable haste.

Whoosh!

Burly Neubauer arm-rolled a leaping von Brauchitsch from his blast furnace of a cockpit and beat at the flames with that flag. A crowd peering over railings atop the garages scattered.

That choreographed order was restored impressively quickly and the charred but not yet chastened von Brauchitsch climbed bravely back in, to thunderous cheers.

His moment – and Seaman for that matter – had gone, however, and Manfred would return to the pits on foot brandishing the steering wheel that he claimed had become detached and caused him to crash at 120mph.

Now with a huge lead over Lang, who had relinquished his own in order to assume Caracciola’s better-placed car, Seaman was alone with as many thoughts as 485bhp on hard, skinny tyres would allow at the be-hedged Nürburgring.

There was much to mull: the achieving of a lifetime’s ambition; his fiancée, whom he had met just weeks before and who was the Anglophile teenage daughter of the boss of BMW; and the ramifications of that as well as victory in the most highly charged race of the year.

He probably guessed that the clouds of war would soon occlude his zenith.

His Nazi salute, when it came, sagged somewhat from the elbow – in contrast to those thrusting beseechingly skywards beside him – as he realised that winning for the love of your machine had been replaced by the honour of one’s country.

His wish that he’d been driving a British car was wistful rather than flagrantly nationalistic. Simply, it would have made things so much simpler.

Of course they would become more difficult.

Seaman’s homecoming at October’s Donington Park Grand Prix was delayed by three weeks because of the Munich Crisis.

And in 1939, by now married to Erica Popp and living near Munich – and written out of the will in consequence – Seaman’s only source of income had many uncomfortable strings.

Letters of advice from BRDC President Earl Howe were already making mention of incarceration in concentration camps.

Untenable decisions would have to be made – but first an increasingly rare opportunity: the Belgian GP in late June.

Seaman never would come home, never would fly a Spit’ or Hurrie, for instead, he suffered ultimately fatal injuries when he pressed too hard in the wet and crashed from the lead at Spa.

The conflict of arguably the first of The Few was over. The world’s was about to begin.

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

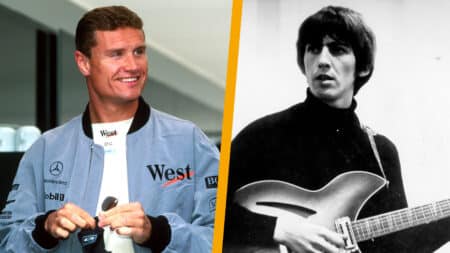

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song