MPH: To the man trying to fill Christian Horner's shoes: good luck!

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

Massa: he’s got to go, hasn’t he?

He’s not been the same since that bang on the bonce. That’s harsh, particularly on such a good bloke – a honourable man who was world champion for 38.907 seconds in 2008 – but it is undeniably true.

Ferrari insists that it is evaluating his future, presumably a ploy to avoid upsetting Fernando Alonso at this crucial juncture, but to hand the Brazilian another stay of execution would be a sign of weakness on the Scuderia’s part.

Massa drove superbly on that memorable day at Interlagos. His performance reminded me of Jean-Pierre Jabouille’s at Dijon in 1979: wondering what all the fuss was about as he cruised to the first win for Renault’s turbo. Massa also won from pole (and set fastest lap). It was his sixth victory of a slickly constructed campaign.

He hasn’t won since.

He finished a brave and encouraging runner-up at his return race, Bahrain in 2010, but has added only two more second places to his tally: Germany, also in 2010, and Japan last season. There have been five thirds, too, the most recent being in Spain in May.

For such an obviously emotional performer, he has kept his frustration and disappointment impressively bottled, but the increasingly nanny tone of his race engineer Rob Smedley’s voice – a simpatico pair that you can but warm to – gives the game away: they know it is slipping from their grasp and that time is ticking against them.

They turned it around – just – in the second half of last year, but more of the same this year should not warrant another extension of Massa’s contract. That would be a waste of what ought to be a prime seat.

Worryingly for Massa, the patterns seem ingrained. The better the Ferrari and, therefore, the easier it is to drive, he is able to match and even beat Alonso over a single lap. Come the races, and no matter the tune of their mounts, the latter rampages forward while Massa, who appears as flustered behind the wheel today as he did when Sauber signed him before he was ready (in 2002), slips inevitably rearward.

A sabbatical as Ferrari’s official test driver in 2003; two, more cogent, seasons with Sauber; plus a year under the tutelage of an unthreatened Michael Schumacher polished what Ferrari clearly viewed to be an uncut diamond. And when reigning world champion team-mate Kimi Räikkönen took his foot off the gas in the second half of 2008, Massa finally graduated as a bona fide contender.

All that hard work – and surely it had been a struggle – was undone by fate at Hungaroring in 2009. Thankfully, Massa survived that ugly impact – only for the knife to be cruelly twisted.

I don’t know what the cause/s of his problem/s is/are. But then neither does Ferrari. Either that, or it doesn’t want to fix it/them, which is worse. It’s as if it has given up on the constructors’ trophy, which it hasn’t won since Massa hit his straps six seasons ago.

A scheduled morning run at tomorrow’s final day of Silverstone’s repackaged Young Drivers’ Test – the embarrassing naughty-schoolboy overtones in Massa’s case are unavoidable – might well be his final throw of the dice in a bid to find that elusive sweet spot. Sadly, there is a gnawing inevitability to his inability to do so.

Being a number two, especially when you have enjoyed and profited from a spell as a number one, de facto or otherwise, is never easy, particularly at Ferrari. Fiery inaugural world champion ‘Nino’ Farina railed against it in 1953. Easygoing Chris Amon, who carried the team through perhaps its bleakest period, rightly got the hump when he discovered that Jacky Ickx, his new team-mate for 1968, was on a considerably better screw than he. Didier Pironi was shocked to the core to discover that he was not the world’s fastest driver when he joined alongside Gilles Villeneuve in 1981. ‘Il Leone’ Nigel Mansell left in a huff at the end of 1990 after Alain Prost had taught him that being stupendously fast is not necessarily enough. Even the beatific Rubens Barrichello ran out patience after six seasons under Schuey’s thumb.

What’s more, Massa has been Alonso’s number two since the Spaniard, then battling Lewis Hamilton to be top dog at McLaren, ran around the outside of him at the Nürburgring to take the lead of the 2007 European Grand Prix and basically told the complaining Brazilian to man-up as they waited to ascend the podium. They appear to get on well as team-mates, but their pecking order is cringingly obvious.

So what will Ferrari do?

You know, I think it’ll keep Massa on.

It allowed Schumacher four seasons before he won the 2000 title at 31, the age Alonso is now. Several seasons of stupendous success, bar 2005, followed.

The unpicking of that Todt/Brawn/Schumacher triumph-virate was meant to ensure Ferrari’s future success. It may well yet – but the pain of regrowth was absolutely guaranteed. And in this difficult circumstance, Alonso continues as its ace card (although he, too, knows that a world title must come soon for his position to remain sacrosanct). So why risk trumping him with a reluctant number two along the lines of Nico Hülkenberg or Paul di Resta? Especially when the stock of both suggested candidates is, at best, fluctuating.

Mark Webber might have ‘worked’ at Alonso’s Ferrari: fast enough and smart enough to win races while knowing his place – a sort of superannuated Eddie Irvine – but he didn’t fancy it.

Might Kimi? Ferrari has the seen the best and worst of the truculent Finn, but, no.

Daniel Ricciardo has his sights set elsewhere. And Jean-Eric Vergne is, I suspect, about to be unflatteringly shaded by his Australian Toro Rosso team-mate.

Is Valtteri Bottas the next Niki Lauda? Is Adrian Sutil the next Jean Alesi? Is Pastor Maldonado the next Willy Mairesse? No. No. Er, possibly – and therein lies his rub.

Then there’s Jules Bianchi, currently on loan and impressing at Marussia. The Frenchman has been nurtured by Ferrari since 2009 and was immediately linked to a race seat in the absence of the injured Massa. The Scuderia’s eventual call for Luca Badoer instead was damning. Yes, Bianchi had just turned 20 at time but, if you are good enough, you are old enough.

Another Young Driver worthy of consideration is Robin Frijns, the Dutchman who beat Bianchi to the 2012 Renault 3.5 title but who is now treading water in GP2. But neither he nor Davide Rigon, Ferrari’s incumbent whizz-kid, albeit at 26, possess the same frisson as did Ricardo Rodríguez (1961), Amon (1967) and Villeneuve (1978), the Scuderia’s most recent hunchy punts on ‘unproven’ talent.

António Félix da Costa, a 21-year-old Portuguese, perhaps does, but street-smart Red Bull has already got its horns into him.

And so we come full circle. Massa: he’s going to stay, isn’t he?

Weakened, Ferrari is no longer able to choose from the pick of the crop. There was a time when its second (even third) seat was considered prime. There was a time when it deemed playing off its drivers against each other to be incentivising as well as incendiary. Block-vote Schumacher changed all that and the team reaped the rewards. Now, however, it is paying the price – of which Massa’s continued presence is the physical manifestation.

That’s harsh, too, but (un)deniably true.

Click here to read more on Formula 1

Laurent Mekies arrives as Red Bull F1 team principal with a series of immediate challenges to solve and long-term issues to tackle. He'll either sink or swim, says Mark Hughes

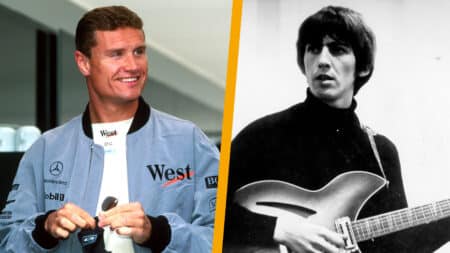

Former McLaren F1 team-mates Mika Häkkinen and David Coulthard are set to renew old rivalries in a new Evening with... tour – they told James Elson all about it

In Formula 1, driver contracts may look iron-clad on paper, but history shows that some of its biggest stars have made dramatic early exits

Former McLaren F1 ace told James Elson about his private audience with The Beatles' George Harrison, who played an unreleased grand prix-themed song