Beneath the Surface: Exploring the Audi DNA in Bentley's Le Mans Success

Bentley conquered Le Mans all over again in 2003 with this stunning Speed 8. Just don’t suggest it’s a German car in disguise…

Matt Howell

Photography Matt Howell

Taken from Motor Sport April 2012

Unalloyed triumphs are rare events. With almost every victory comes a tinge of regret, a sense not just of a job well done, but ways in which it could have been done even better. Bentley’s successful three-year campaign to win the Le Mans 24 Hours at the start of this century is the perfect case in point.

The history books show that at its first attempt, Team Bentley placed third in 2001, a podium position behind two realistically unstoppable works Audi R8s. In 2002 with just one car entered, it came fourth and once more first car home behind the factory R8s. In 2003 with only private R8s to contend with, two Bentleys entered, placing first and second. In all three attempts, amounting to well over 100 hours of racing, one car retired due to freak weather conditions, but none was ever pushed back into the pit garage for repairs. Indeed the winning Speed 8 in 2003 spent a grand total of 17 unscheduled seconds in the pits, an unparalleled achievement in the history of the race. Who could want for more?

The source of dissatisfaction is two-fold, neither being the obvious fact that Bentley didn’t win every Le Mans it entered. I was in their pits for the duration of all three races and not once was there any sense that the team was punching below its weight. Indeed most of the time they exceeded every expectation. I know, for instance, that the never-communicated internal goal for 2001 was for one car to get home in the top 10. A podium was undreamt of. No, what still rankles in certain Bentley circles to this day is, first, that the team did not defend the victory in 2004 and, second, that the perception still exists that the EXP Speed 8 (or Speed 8 as the 2003 car was known) was actually an Audi R8 with a roof.

On the first point I can remember at the time quizzing Bentley’s Franz-Josef Paefgen, then chairman of Bentley and in charge of all VW’s motorsports projects, about his decision not to go back to Le Mans in 2004 when it appeared clear the Speed 8s would have to do little more than turn up to be assured of a second triumph.

I remember pontificating about how no one remembers a single Le Mans win – citing BMW’s 1999 victory as an example – and how as WO proved in the ’20s, if you’re to derive real value from a campaign you need to win and win again, leaving an indelible mark on the event as Jaguar, Ford, Ferrari, Porsche and now Audi have done. His view, expressed with impressive candour, was that I was being naïve: the purpose of the project was to help transform the image of the company ahead of the late 2003 launch of the all-new Continental GT road car, the machine that would entirely transform Bentley’s business. That job had been done and millions spent not just on racing but also designing the road car and rebuilding the factory: now it was time to sell some cars and gain a return on that investment.

“There was more British content in the Audi, than German content in the Bentley”

As for suggestions that the Speed 8 was an R8 coupé, genuine bafflement exists even today. “I guess we just didn’t do that great a job communicating it at the time,” says Bentley’s engineering guru Brian Gush who was instrumental in the entire project from its earliest days and, with Paefgen’s predecessor Tony Gott, probably campaigned harder and for longer than anyone to get Bentley to La Sarthe. Brian’s killer fact, which I don’t remember from any press release, is that there was more British content in the Audi than there was German content in the Bentley. “But people saw that we used an Audi engine, knew we both belonged to the same group and came to some inevitable and entirely wrong conclusions.”

A man with an even greater right to be cheesed off with this perception is Peter Elleray, the man who designed both the 2001-02 EXP Speed 8 and the all-conquering 2003 Speed 8.

“It’s just sheer bloody ignorance,” he says, still railing against the notion well over a decade later. “It’s true the R8C was designed at RTN,” he says, referring to the Audi coupé that proved completely inadequate at Le Mans in 1999 and Racing Technology Norfolk, the factory where the racing Bentleys were created. “So yes, we had that knowledge. But engine aside, there was not a single thing on the Bentley that had anything to do with the R8C or, indeed, any other Audi.”

Frankel pauses with the Speed 8 before trying to thread himself into the cockpit’s tight confines

Matt Howell

So how did it all start? Though rumours had been flying for a while, the first the public knew that Bentley’s lifetime of waiting to return to Le Mans was shortly to end came in a release dated November 4, 2000.

Two cars would contest the race the following summer. Unlike any others in the race, they would be closed prototypes and while they’d be tested and raced by the late Richard Lloyd’s Apex Motorsports, the contract to build and develop the cars went to RTN in facilities that house – at least for now – the Caterham Formula 1 team. Outwardly Bentley Motors, RTN and Apex would come together to form Team Bentley, but internally the return to Le Mans was always known as ‘Project Barnato’ after Bentley’s former chairman and still the only man to race at Le Mans just three times, and win every one of them. The steering committee was led by Gush.

The decision to make a closed car was the result of a careful balance of attributes. On the downside it would be more complex because of the screen, wiper and door systems, it would carry more of its weight higher up, the rules mandated it had to have narrower tyres and pitstops would take longer. On the other hand, there was a larger restrictor, a smoother route for the air to take to the rear wing, and while the narrower tyres meant less mechanical grip, they impeded air flow under the car less, so this could be balanced by better aerodynamics. It would also look nothing like an Audi R8.

There were problems from the outset. Audi couldn’t supply any engines until March, so the car spent most of its development powered by a Ford DFR unit which had similar power but a fraction of the torque of the Audi turbo. James Weaver was enlisted to do all the testing but quit the team long before the race. So one car would be driven by sports car stalwarts Andy Wallace, Butch Leitzinger and Eric van de Poele, the other by none other than Martin Brundle, partnered by Stephane Ortelli and a relatively unknown youngster, Guy Smith.

The official Le Mans test went well; too well according to some. Brundle put in a lap that placed the Bentley far closer to the Audi R8s than anyone had expected, Audi included. Yet come qualifying for the actual race some weeks later, he couldn’t get within 2sec of the time. Conspiracy theories abounded about the health of Audi’s race engines relative to the test weekend units.

Even so, Brundle still managed to startle everyone by leading the race at the end of the first hour: it was raining, the car running on Dunlops which had had almost no wet weather development compared to the Michelins on all the other front-runners; but some canny tyre choice by team manager John Wickham and Brundle’s talents allowed Bentley, briefly, to head the field.

But euphoria soon turned to despair as the car retired with Smith at the wheel, stuck in sixth gear at Arnage. Water had got into and scrambled the gearbox actuator; worse, the second car was showing symptoms of the same problem. What happened next has become part of Bentley lore. Leitzinger got stuck in gear too, but mercifully only fourth, which allowed him, just, to get to the pits. There the actuator was changed and the water’s ingress stopped by the strategic positioning of the top of a bottle of mineral water. Thereafter the car ran near-flawlessly to the flag, and third position. Richard Lloyd, among many others, shed tears of joy.

The 2002 race was one of consolidation. Bentley knew it needed a new car to keep up with the Audi R8, of which three works units were entered. So just one EXP Speed 8 took the start, crewed by the same team that had come third the year before. And once more they were best of the rest behind the works R8s, but this time that meant just fourth.

“I expect we told them we were doing a comprehensive update for 2003. In fact we started again from scratch”

And so to the 2003 season and Peter Elleray’s Speed 8. “I’d had the idea for the car a while back,” he says, “but I didn’t feel well enough established to stand there in the early days and state ‘this is what we need’. But after the 2001/2002 cars, things were rather different. I expect we told Dr Paefgen we were going to do a comprehensive update. In fact we started again from scratch.”

It was as bold as its predecessor had been conservative and it would be driven by an almost completely new set of drivers. One car would be allocated to Johnny Herbert, Mark Blundell and David Brabham (Allan McNish had been approached but had chosen not to give up his Renault F1 testing contract), the other to Tom Kristensen and Dindo Capello, on loan from the works Audi team currently on sabbatical from sports car racing. They would be joined by the sole survivor from the EXP Speed 8, Guy Smith, who’d sat out 2002 as Bentley test driver and turned down many top drives as a result. The reward for such loyalty would be as great as it was deserved.

The Speed 8s went to Sebring, the first time a works Bentley had raced in America since a car was entered into the 1922 Indy 500 and came last. In qualifying the cars destroyed the field, but still started from the back because of a technical infringement that almost certainly harmed their performance. The R8s had no such problem and fled, leaving the Bentleys too much work to do on the tight, twisting circuit. A dozen hours later they were, yet again, best of the rest in third and fourth behind the Audis. It was becoming a habit.

The story of Le Mans 2003 is swiftly told. Capello qualified the lead Speed 8 almost three seconds faster than the quickest (privateer) R8, Kristensen started the race and took a lead which the car still held 24 hours later when Smith drove it over the line to win. The second car, after a smattering of small but annoying issues, came second, three laps clear of the closest R8.

The winning moment in 2003

Matt Howell

Interestingly, while there was much satisfaction in the team at the victory, the scenes of wild jubilation that broke out in 2001 were nowhere to be seen: celebrations were almost muted by comparison. And it is easy to see why: that year and for the first time, Bentley had the best car, the best team – with assistance from Audi’s respected Joest squad – the best drivers and little comparable competition: anything less than victory would have been defeat. In 2001 in particular, equipped with a good but not great car, the new team punched monstrously above its weight to achieve a result of which few would have dared to dream.

“If you’ve got to stop somewhere, where better than right at the top?

And as for that much discussed return to Le Mans in 2004, while Gush would have loved to go back and at the time put forward a formal proposal to do just that, Elleray puts a different spin on the subject: “Do you know what I’d have hated? Going back in 2004 but without the likes of Tom and Dindo who were still on Audi contracts, without the best pit crew because the Joest boys had gone with them, with customer engines and a non-works tyre contract. Funnily enough I think we might still have won it, because the Speed 8 was so good, straight out of the box. We set it up but did very little development work on it. What ran for the first time in January 2003 is pretty much what won the race in June. But that was the perfect race. We could never have done any better. If you’ve got to stop somewhere, where better than right at the top?”

So it is to Bentley’s eternal credit that it has kept the Speed 8s working and to my eternal good fortune that late last year, Gush rang and said, “remind me how tall you are.”

I’d never driven a modern sports prototype before. My first-hand knowledge of Le Mans cars logs off with ’80s Group C machinery, veritable dinosaurs compared to the Speed 8 now sitting in the pitlane of the extended and transformed Stowe circuit at Silverstone. Gush and Smith are in attendance and much amused by my flailing attempts to thread my way into the Speed 8’s dark interior.

“You need to sit on the side, hold on to the roof, swing your legs over, squeeze your feet under the wheel and then shuffle your backside across,” is the advice of Ash Mason, the man responsible for running the Speed 8 today. Happily while getting in is murderous, once in place the car fits well. I’m almost comfortable.

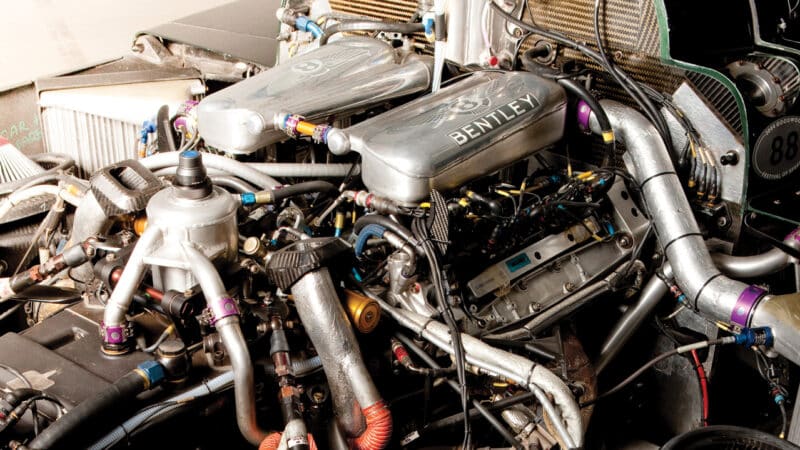

The Bentley’s Audi engine displaced four litres

Matt Howell

Which is not to say it’s even close to relaxed in here. Visibility is terrible – if I look straight ahead all I can see is the opaque strip at the top of the screen. Below that is a small letterbox of glass and to either side there are a couple of portholes cut in late in the car’s development to allow just a trace of peripheral vision. You can see very little behind you even with the external mirrors but then I guess in a car like this anything that was behind you was likely to be staying there.

Guy leans in, keen to calm my nerves. “You’re lucky you’re not driving the older car,” he says. “That was a pig in the cold. Jumped about all over the track. This one’s very easy.” To which Gush adds, “but just remember you’ll have no brakes, no grip, no traction control or ABS and if the back goes, it stays gone.”

He’s right. The track is damp, the air temperature a degree or two above freezing. I’m grateful for a set of new intermediate tyres but in this weather I doubt I’ll get meaningful heat into either them or the carbon-ceramic discs with pads so hard they’ll do 24 hours without needing to be changed.

Still, Guy is adamant the car is easier and more pleasant to drive than an R8 and he should know: he drove one to second place the year after he won in the Bentley. The key difference is that while the Audi had a 3.6-litre engine, the Speed 8 unit displaces four litres. A small restrictor means there’s no more power, but it is much more driveable. Apparently.

I’m not sure why, but I expected a twin turbo V8 in the back of a Bentley to be a smooth and silken affair. It’s not: it fires up and idles angrily with all the charm of a prodded dragon. Compared to, say, a Jaguar XJR-9LM or a late Porsche 962, its 600bhp is comparatively little, but compared to most other 900kg cars, it’s palpably absurd. And it has torque you would not believe. There are LCD readouts all over the place but I’m told to focus on oil and water temperature: the Speed 8’s cooling system was designed to work with hurricane force air over its radiators, not for crawling around at 40mph behind a camera car. Even in these temperatures it’ll do that for a lap maximum before it threatens to overheat.

And when it does there’s only one thing that’s going to cool it down and that’s being driven fast.

Buried deep inside its cockpit and hardly able to see out, engine shouting and snarling, I find the throttle pedal is as intimidating a thing as I’ve stood on in a while. The performance is instant and brutal. There’s no pause, no lag waiting for the boost to arrive as you do in a Group C Porsche – the Bentley just launches itself at the far end of the track. Your very next thought is that those cold inters have started to spin up and the one after that is that this is very senior indeed.

Go up a gear and hope it calms down a bit. Hope in vain. This time the tyres grip properly and you feel like an innocent bystander granted brief access to someone else’s vision of pure madness. There’s a corner coming and I’ve already forgotten Brian’s warning about the brakes. The pedal is as hard as the bulkhead and about as effective at slowing the car. Right now, you could be comprehensively outbraked by a child’s bicycle. But there’s nothing else to do except pray and when the brakes do arrive they’re so strong you have to bleed off the pedal almost at once to stop the fronts locking. And they raced this for 24 hours?

Happily I’ve driven enough to know that almost without exception, when confronted with an apparently impossible device like this the trick is not to slow down, but speed up. Moving the car nearer the parameters in which it was designed to work, all the way from engine revs to tyre temperature, is almost bound to make it easier to drive.

And so it proves. That stupendous slug of torque becomes a friend not an enemy. You don’t need to focus on what revs you’re pulling or which gear you’re in because from 3000rpm onwards, the Bentley just goes. The paddleshift gearbox, given a full throttle upchange suddenly becomes miraculously smooth. Heat in the tyres means they’re less inclined to spin and lock and if the back does start to move, as it very easily will with too much power too early, the car will return faithfully to your chosen line, so long as you correct and lift the instant you feel it. The next day, with me stuffed into the ‘passenger seat’ of a 2001 EXP Speed 8, Guy would prove it could actually be drifted.

Of course the dream would be to let it loose at Le Mans – nailing the throttle at the exit of Mulsanne, hitting some really silly numbers as you rocket down to Indianapolis and feeling the downforce sucking the life out of your neck muscles through the Porsche curves.

“Does it matter that, engine aside, it’s British from end to end? It probably shouldn’t, but it does. This is a Bentley after all”

But even on the Stowe circuit I thought I could glimpse why the drivers loved this car so much. In its day it was the quickest sports car the world had yet devised. But it was so much more than that: when it really mattered, it was faultlessly reliable, staggeringly strong (Johnny Herbert walked away from a testing accident he described as “the second-biggest of my career”) and knee-weakeningly beautiful.

Does it matter that, engine aside, it was also British from end to end? It probably shouldn’t but it does. This was a Bentley after all, and though it was designed and built by others (just like Jaguar’s Group C cars) the programme was devised and developed by Bentley in Crewe. It brought inspiration to a workforce, and pride to a nation that had waited over a dozen years for a British car to win Le Mans again.