While Audi Sport UK pressed ahead with its car in isolation, the Audi R8R that was being developed in Germany bore a striking resemblance to the Ferrari 333SP, having based its design on the already successful model. It was similar enough to the Ferrari that the team called it the Ingolstadt Ferrari. The basic packaging of the car saw the positioning of the radiators and the double roll hoop a carry-over from the Ferrari, although the finer details, such as the front suspension pick-up points, were different.

“I told Emmanuele that Ferrari had run like that for years and nobody has been grilled yet”

The radiator at the front was clearly an issue in the first test at Sebring. ‘Emmanuele Pirro drove the car and complained at the heat coming into the cockpit,’ remembers Ullrich. ‘I told him that the Ferrari had run like that for years and no driver had been grilled, but he was not amused. He came into the pitlane in Sebring and made a sign for me to come over to the car and said I should drive it down the pitlane and back to the tent. I did it and for sure it was warm, but in Spa I think they would have asked for this heating.’

The R8R was pronounced ready to run at Sebring in March 1999 but, with such a new programme, there were teething problems. The strength of some of the carbon fibre parts commissioned from various companies were found to be inadequate, so new parts had to be ordered.

“The R8R was flexing on the front so much, we were testing in Daytona at the end of 1998 and there was a Riley and Scott private team,” remembers Team Joest’s former technical director, Ralf Juttner.

“Michele [Alboreto] always pitted complaining that the car was vibrating like hell. We tried using wires to hold the splitter lip, but over 250km/h everything was flexing. Once he got on the radio and said he was coming past the pits and told us to watch, and the thing was flexing badly. Watching the car going down to the first corner, we had a team of 30 or 40, all in Audi red, and [also testing there was a] privateer team of four. They watched the car as well and, as it went into turn one, they turned to us and applauded. It was so embarrassing.”

Joest had already worked with David Price at Surrey, UK-based DPS Composites on its 962 and WSC car and therefore the company capable of producing the quality of parts needed to make the car work properly. As this version of the R8R was left clearly wanting, a secret design was commissioned. It involved a whole new front end that fitted within the original bodywork but had improved airflow and strength.

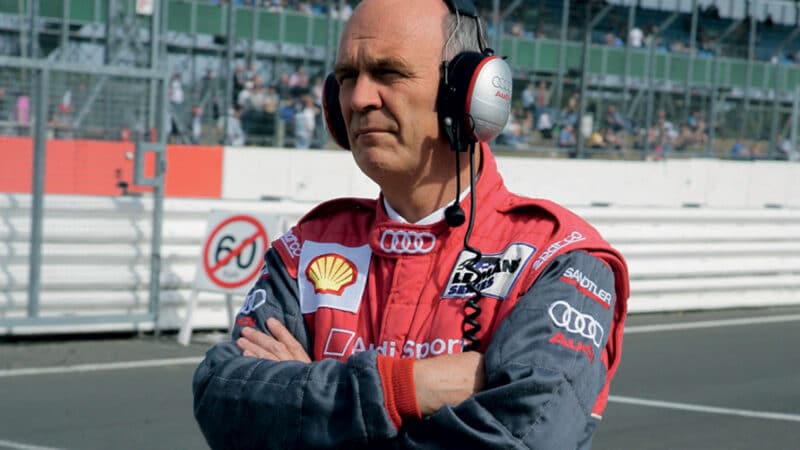

Wolfgang Ullrich oversaw the team’s rise to success

Audi AG

“A designer we knew very well made a new design of the front end, including the splitter, the nose and the radiator, ducting, radiator mounts and fixation, but with the same aero,’ recalls Juttner. ‘Dr Ullrich knew about it, but the design department didn’t. The underfloor was all the same, but the mounting was different, and it was designed for stiffness, built by [David Price at] DPS.”