The quality of the reel earned the filmmakers unprecedented access for the rest of the shoot. Ferrari allowed the crew inside its production floor and up close with the race day cars and many drivers agreed to appear in the film, including six world champions: Phil Hill, Graham Hill, Juan Manuel Fangio, Jim Clark, Jochen Rindt and Jack Brabham.

The final film also included some of the earliest experimentation with in-car cameras for F1, particularly in terms of POV shots that would allow audiences to imagine themselves in the driver’s seat. Phil Hill even drove a modified camera car in some sessions during the actual grands prix. The combination of real-life race footage and the spectacular movie footage shot on location (with Formula 3 cars mocked up to look like F1 models) would go on to influence pretty much every racing film ever made since.

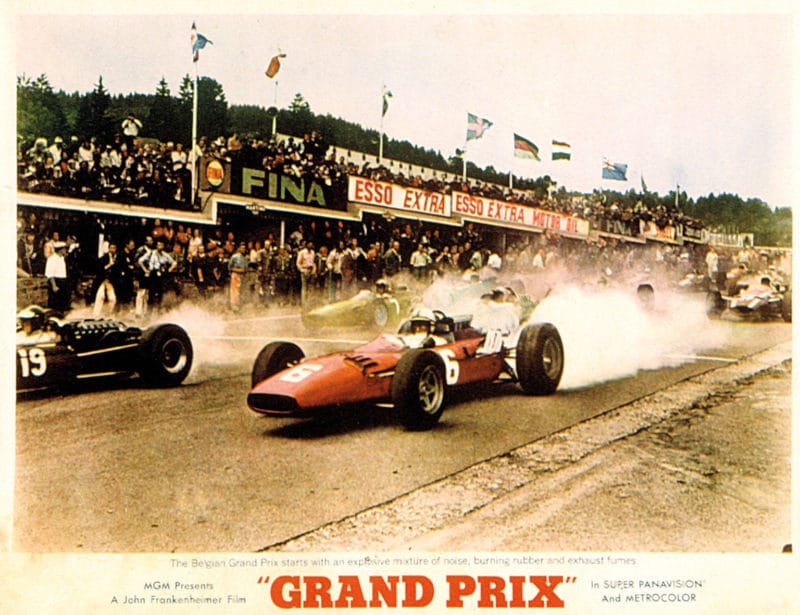

In the quest for authenticity, Grand Prix did its shooting at many actual races, recreating scenes on location

As Peter Yeats, director of Bullitt, observed: “Frankenheimer had a reputation for always doing things in the most difficult way possible but that was because he was always after realism. And with Grand Prix you see the result of that quest: as you’re watching you have this feeling of it actually happening. It’s why I don’t think the film really dates.”

“The crowds are real… as is the excitement!” declared a promotional piece made at the time of filming that shows Frankenheimer’s crew and cast mingling on the streets of Monaco on race day, wheeling their Super Panavision cameras past the palm trees and impossibly stylish artefacts of the times – cars, yachts, helicopters, sunglasses-wearing jet setters and bohemian locals with jumpers draped over slim shoulders, leaning on stunningly beautiful sports cars. Throughout the promo, every street is crowded with noise and colour and movie stars – Yves Montand, Françoise Hardy, Eva Marie Saint, Garner (who at one point gets into a row with a local shopkeeper trying to fleece the crew out of more money) – while Frankenheimer, his dark hair slicked back a la Elvis, prowls around intensely, occasionally looking like he’s about to erupt (he was a serial swearer on set). The camera operator, John M Stephens could often be seen precariously hanging out of a helicopter to capture aerial shots (“It was the most exciting motion picture I ever worked on.”) and all the crew eagerly utilised any colours and sounds available to them – when Jackie Stewart celebrated his victory, they capture Montand mirroring the celebrations for the movie. The line between reality and fiction at times got blurred.

The crew would even shoot around real accidents to create more footage. (Though for the film’s more spectacular crashes, they would use hydrogen cannons to fire cars through the air with dummies in the driver’s seat). There’s a point in the finished film where Garner appears to be on fire. It’s not a special effect. He did indeed catch light as the crew scrambled to put him out.

“The insurance company cancelled my insurance after that,” recalled Garner, who shot the final month of the film uninsured. It’s an astonishing way to make a movie and probably impossible to replicate today as F1 is simply too polished, too commercial and too controlled to allow a crew the same levels of access or the same opportunities for happy accidents. But in 1966 Frankenheimer managed to corral 205 people and 65 race cars across nine countries in order to capture the feel of a real season.

“I don’t know how we did it,” admitted Garner decades later. “You’d have to hand it to Frankenheimer. He pushed people to their limits to get it done. We got as close as you could get, at that time, to what racing is all about.”

At first, Formula 1 teams were dubious and unwelcoming to the production crew, but after they saw some B-roll, many were only too happy to get involved in the project

Getty Images

Of course, the finished film isn’t just a racing travelogue. Grand Prix’s three-hour runtime also includes oodles of angsty and existential drama to create a proper old school Hollywood melodrama. Frankenheimer didn’t just want to capture the feel of a race. He wanted to capture the feeling of a whole season. Hence Grand Prix’s array of colourful characters.

There’s Garner’s Pete Aron, hot-headed and reckless but given a chance to step up from also-ran status when he signs for an ambitious new team (run by Akira Kurosawa regular Toshiro Mifune). Aron’s main rivals are Antonio Sabàto’s brash young Italian wannabe Nino Barlini, Brian Bedford’s troubled Brit Scott Stoddard and (arguably the film’s lead) Yves Montand’s Jean-Pierre Sarti, an ageing two-time world champion now growing increasingly cynical about the sport. There’s also ‘The Women Who Love Them’.