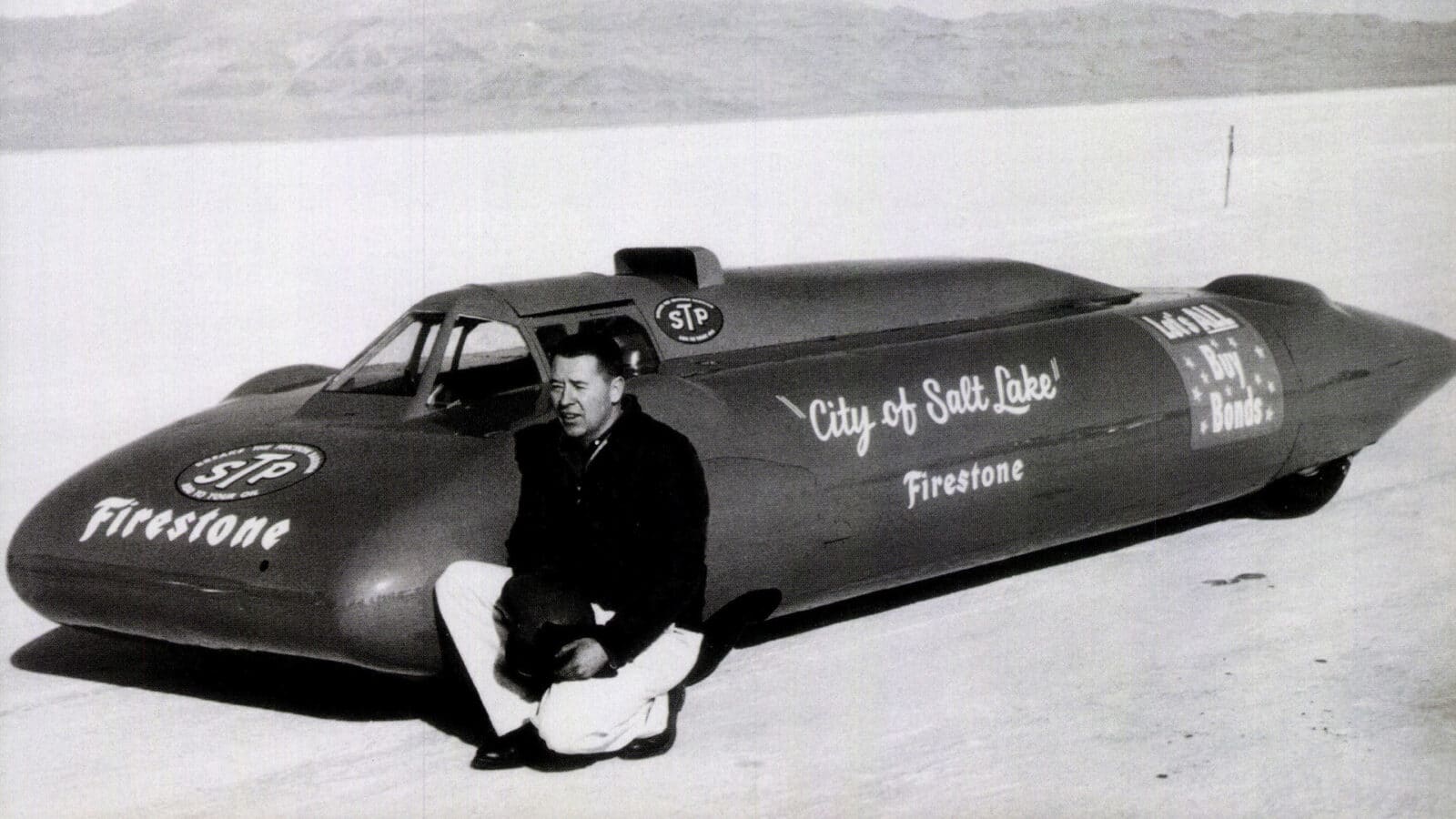

In 1958, Graham turned his dream into reality, in the form of a car dedicated to his beloved Mormon State Capital the ‘City of Salt Lake’. Its power came from a 3000hp USAF-surplus supercharged V12 Allison aero-engine. This particular unit had been fitted to William E Boeing Jnr’s unlimited hydroplane ‘Miss Wahoo’, which Jack Regas had piloted in the 1957 Gold Cup on Lake Washington. Graham mounted the powerplant in the rear of the car, driving the rear wheels.

The streamlined body-shell was fabricated around a drop tank taken from the belly of a World War II Boeing B-29 Superfortress, cut into three sections to form the nose, centre, and sandwiched tail section, aft of the engine housing and fuel tanks. The chassis was made of 12in-deep aluminium and incorporated stock Cadillac components throughout.

Most experts, including Mickey Thompson, opined that the car lacked aerodynamic co-efficiency and would prove unstable without a tail fin. How right they were.

On the morning of August 1, 1960, Graham made his final attempt on Thompson’s flying mile record. Shortly before 9.15am, he fired up his STP-and Firestone-backed $2500 vehicle. But just two miles down range, the car veered slightly off course, began to slide, pitching violently, turned, became airborne and crashed. Violently.

Graham wasn’t wearing a seat belt or safety harness. On impact, the firewall shattered the cockpit and broke the driver’s spine. Athol died three hours later in Tooele Hospital.

It was thought he had accelerated too hard, causing the left-rear hub to shear off under the load of the tremendous torque transmitted at the start of the run.

That should have been the end of the ‘City of Salt Lake’.

It wasn’t.

In the aftermath of Graham’s death, Otto Anzjon, a 17-year-old mechanic from Salt Lake City, persuaded Graham’s widow Zeldine to let him rebuild the car for another crack at the record in 1962. The idea of breaking the LSR, after witnessing his hero lose his life in the car, perhaps stemmed from a young man’s impetuosity but it was certainly indicative also of his courage and determination. Anzjon was made of the stuff of heroes.

Duly concerned by the car’s unfortunate history, Joe Petrali, Bonneville’s wise elder statesman, counselled the inexperienced Anzjon regarding a number of design changes he considered mandatory for a fresh attempt. But with very little funding and, as it transpired, very little time, a compromise was agreed: the car would be run with a small device to measure the loads on the troublesome rear axle.

“The idea of rebuilding the car was all Otto’s,” explained Zeldine Graham. “I would never have asked him to race, but he has expressed a very strong desire to fulfill Athol’s dream.”

And the man himself?

“I guess I should be scared, but I’m not,” Anzjon told Petal “My parents say it’s okay, and I am most eager to drive the car.” He attained an impressive 254mph on his first one-way pass across the salt, and Zeldine quickly applied to Petrali for a record attempt sanction. Anzjon was roaring past the timing beam in excess of 200mph when the left-rear Firestone suffered a blowout. ‘City of Salt Lake’ once again pitched, turned and crashed.

Anzjon survived but never got another opportunity to drive the car, for leukemia claimed him in the winter of 1962 and, like his hero, he died in Tooele Hospital.

That should have been the end of the ‘City of Salt Lake’.

It wasn’t.

It was re-rebuilt and, on the October 12, 1963, Harry Muhlbach hurtled it down Bonneville’s course at an estimated 395mph which is when the car veered out of control, pitched violently, turned and crashed, sliding upside down for over 1000ft before coming to a halt.

Muhlbach survived, but the car’s reputation did not. Both STP-and Firestone withdrew their support.

This was the end of ‘City of Salt Lake’.

One final irony: Zeldine worked at Tooele Hospital.