He was not. He had been sitting there for miles, lights off. If there can be no sweetness in defeat, perhaps Varzi was consoled by the implicit compliment he had been paid.

Four years later, in Alfas again, it was Nuvolari who had the earlier start time, Varzi who passed him, and who went on to win. But by now grand prix successes were coming hard for them. German domination was dawning, and while Tazio committed himself to the Scuderia Ferrari Alfas for 1935, Achille signed with Auto Union. It was this decision, again taken for entirely logical reasons, which led ultimately to his downfall.

The association began well. With talent as natural as his, Varzi adapted readily to the immense power and wayward handling of the rear-engined cars, and won at Tunis and Pescara. By common consent, he was at the height of his powers.

Early that year, however, he had met Ilse, the stunning wife of Paul Pietsch, Auto Union’s young reserve driver. An affair began almost immediately, discreet only for a while; soon they were together everywhere.

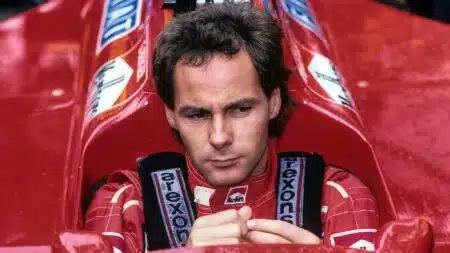

(From left) Varzi, Hans Stuck and Bernd Rosemeyer

Audi

For 1936, Varzi remained with Auto Union, his team-mates Hans Stuck and meteoric Bernd Rosemeyer. All was well until Tripoli, his favourite circuit He had won there twice, and now came a third victory, from Stuck, whom he overtook on the run-up to the line. On the last lap – this is 66 years ago – he had averaged more than 141mph.

Auto Union team orders had dictated that, Libya being an Italian colony, Varzi should win. At the banquet that evening, the Governor of Tripoli asked for silence, lifted his glass and proposed a toast to the winner… Hans Stuck! There was, said Manfred von Brauchitsch, an excruciating silence. Then Varzi, humiliated, stalked out.

“The morphine had complete hold, and he was slipping away from reality”

His mind in turmoil, he found sleep impossible, and it was then that llse held out a syringe. They had been together a year, but this was the first he knew of her addiction, which had started in hospital after an operation. Hours later, still sleepless, he gave in.

Had he been an undisciplined man, the change in Varzi might have been imperceptible for a while. But in one such as he, the transformation was startling, apparent in Tunis only a week later. Never exactly garrulous, now he chattered, then lapsed into bouts of silence. As well as that, his driving was stripped suddenly of its precision. That weekend he had the first major accident of his career, the Auto Union somersaulting at around 150mph. Somehow he came out of it without injury, too shocked even to hold a cigarette.

At the end of the season, Varzi disappeared. Even his parents didn’t know where he was, but Auto Union finally traced him to Rome, where he was existing, according to the team’s doctor, on champagne, coffee and cigarettes. The morphine had complete hold, and he was slipping away from reality, an old man of 32. Not surprisingly, Auto Union decided against a new contact for 1937.