Nigel Roebuck’s Legends: Rob Walker – the gentleman F1 boss

The scene: the Glen Motor Inn, Watkins Glen. The date: September 1979. I am sitting at a table with a couple of colleagues, and studying the menu, unable to make…

Suzuka, Sunday October 21 1990. The two engineers, formerly colleagues on the same team, were walking through the day’s events. “Well,” said Tim Wright of McLaren, “that was a bloody waste of everyone’s time, wasn’t it?”

“Yes,” shrugged Steve Nichols, now with Ferrari. “Still, er, congratulations…”

Someone else piped up: “Ron (Dennis) says it would never have happened if Senna had been allowed to have pole position on the left side of the track…”

At that, Nichols erupted. “Jesus Christ, where the hell does this end? It wouldn’t have happened if they’d just given Senna the nine points, and not run the goddam race at all!”

Wright said nothing, just stared at the ground.

Three hours earlier, at 1pm, Senna and Prost had set off to do what they always did at Suzuka in those days: settle the outcome of the World Championship. Within 10 seconds of the start the McLaren and the Ferrari were in the gravel trap, the title now safely in Ayrton’s hands. Into the first corner at 150 mph he never lifted, but simply took aim at his rival. Immediately behind were 24 other drivers, and Prost’s rear wing – sheared off in the impact – could have come down anywhere. To this day it remains the most reprehensible piece of driving I have ever seen in Formula One.

They had history, Senna and Prost, of course, and not only because they were the two greatest drivers of their time. Even before Ayrton arrived in F1, he recognised Alain as a class above the rest, and thus had him in the crosswires from the outset. Prost could live with the idea that there was someone even quicker than himself, but his distaste for Senna’s ruthlessness on and off the track was profound. At Suzuka 12 months earlier he shut the door on his rival at the chicane, and that clinched his third championship.

After this coming-together, Senna had a push start – in the escape road, where the two McLarens had ground to a halt – and went on to win the race, but was subsequently disqualified. In this decision he saw the hand of Jean-Marie Balestre, then President of FISA (then the sporting arm of the FIA), and he didn’t hold back from voicing his opinion.

So to the 1990 race. As in the two previous years, Ayrton was on pole position, which – curiously – had always been on the right side of the track. The ‘dirty side’. Well aware that Prost’s Ferrari was potentially quicker in the race, that the start could be critical, Senna asked for pole to be moved to the left. Request denied. Again he saw the spectre of Balestre, and this time resolved to sort the problem in his own way. Thus, the ‘championship decider’ lasted only seconds.

Afterwards, Senna professed his innocence, said that Prost had ‘left a gap’, but in a press conference 12 months later – in Japan once more – the truth emerged. It was after the race, and Ayrton, confirmed as World Champion for the third time (and with Max Mosely recently elected as Balestre’s successor), was in a sunny mood – until someone asked a question about the two previous races at Suzuka. The room temperature went into free fall.

“I think what happened in 1989 was unforgivable,” Ayrton began, “and I will never forget it. Even now I struggle to cope with it. After I rejoined that race, I won it, but they decided against me and that was not justice. It was theatre, but I couldn’t say what I thought – if you do that you get penalties, you get fined, you lose your licence maybe. Is that a fair way of working? It is not.”

It is not often you get quiet, or anything close to it, during post-race press conferences, but when I listened again to the tape of that one, I was struck by the absolute lack of background noise as Ayrton spoke, his voice ever more impassioned.

“Then 1990 was almost…like, to prove a point. It happened the other way round – like, to show everyone that what you do here, here you pay. I asked the officials to change pole position, and they agreed – but what happened? Balestre gave an order it wasn’t to be changed. I know this from inside the system and I thought this was really shit. I said to myself on Saturday, ‘If, at the start, because I’m in the wrong place, Prost beats me off the line, at the first corner I’m going for it – and he’d better not turn in ahead of me, because he’s not going to make it.

“And it just happened like this. I really wish it didn’t happen, but it happened exactly as it had to happen. He took the start, got the jump on me, and I went for it at the first corner. He turned in and I hit him, and we were both off, and it was a shit end to the championship – not good for F1, not good for anyone…”

Least of all, of course, for Alain Prost, but Senna omitted to mention that fact.

“It was a result of the wrong decision, and partiality from people that were inside then, making some decisions. I didn’t care if we crashed – I just went for it.”

So you did cause it then, came a voice in the audience. “Why did I cause it?” Senna responded. “If you get f***** every time you try to do your job cleanly, within the system, what do you do? Stand back and say thank you? No way. You should fight for what you think is right. If pole had been on the left, I’d have made it to the first corner in the lead, no problem. That was a bad decision to keep pole on the right, and it was influenced by Balestre. And the result was what happened at the first corner. I contributed to it, but it was not my responsibility…”

Recently I have been reading – and much enjoying – the manuscript of Jo Ramirez’s forthcoming book Memoirs of a Racing Man. Ramirez, former McLaren team co-ordinator, was a close friend and consummate admirer of Senna, but this does not make him blind to Ayrton’s foibles. It was that day in Japan, Ramirez writes, which “made me realise he was capable of doing whatever was necessary to secure the title.”

Soon after the debacle at Suzuka, when Senna was still disclaiming responsibility for what had happened, a photographer friend of mine, who had been standing on the inside of the turn and had filmed the whole thing, showed Ayrton one particular shot of the McLaren spearing into the back of the Ferrari. “That’s a lie!” was the response, which rather confirms Ramirez’s view that Senna always believed that they only true version of events was his own. Jo also points out that Ron Dennis was the only McLaren team member to congratulate Ayrton that day.

A couple of weeks later in Adelaide a statement was issued in which Senna was quoted thus: “I now feel that my remarks concerning Jean-Marie Balestre were inappropriate and that the language used was not in good taste.” So this is what Alastair Campbell was doing back then.

No one took any notice of it, of course, because all who had been at Suzuka well knew that Ayrton had been speaking from the heart. It may have been unpalatable, certainly in part, but without a doubt it was born of passion and mercifully free of the political correctness which now suffocates grand prix racing as it does every other aspect of life.

At press conferences today the biggest problem is keeping awake, whether you be a driver, there under sufferance, or a journalist, wearily wondering again how to convert, “We think we’re in good shape for the race, but we’ll see what happens”, into arresting prose. It wasn’t like that with Ayrton Senna.

The scene: the Glen Motor Inn, Watkins Glen. The date: September 1979. I am sitting at a table with a couple of colleagues, and studying the menu, unable to make…

As I drive, each July, from Frankfurt airport to Hockenheim, it is my invariable practice to pull off into the rest area by the Langen-Morfelden crossing on the autobahn towards Darmstadt. At…

It was in the fifties, as a kid, that I fell in love with racing, and it is no coincidence that my favourite GP car will always be Maserati’s sublime…

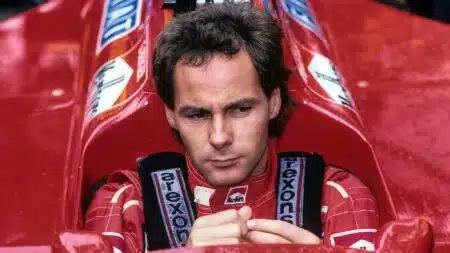

A couple of days before the Revival Meeting at Goodwood, BMW held a splendid lunch in honour of Gerhard Berger, who – for the moment – has left the world…

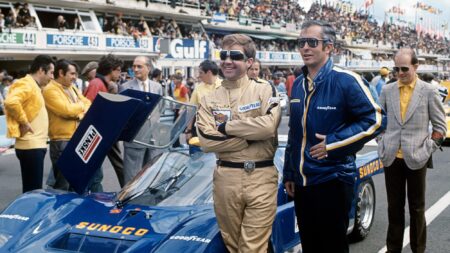

By the end of 1973 Mark Donohue had achieved most of his goals in motor racing. Since 1967 he had worked for Roger Penske, the pair of them synonymous almost…

In terms of world championship races, the 1962 F1 season concluded with a ‘New Year’ fixture at South Africa’s East London. But in those days there were also numerous non-title…

Suzuka, Sunday October 21 1990. The two engineers, formerly colleagues on the same team, were walking through the day’s events. “Well,” said Tim Wright of McLaren, “that was a bloody…

P4. Two syllables to send shivers down your spine — or mine, anyway. In a debate about the best-looking sports-racing car of all time, my choice would lie between the…

Some weekends you can come back from a Grand Prix with a notebook relatively clean. There will be a lap chart in there, of course, together with notes and quotes,…

If ever you were a Lotus fan Goodwood brought it all back. In the paddock, for example, were a pair of Lotus 25s, both ex-Clark, and at the Brooks auction…

Much was made recently of the ‘interminable’ five-week gap between the penultimate and final races of the Formula One season. And certainly it was unusual, given Bernie Ecclestone’s dislike of…

Monza. The 2006 Italian Grand Prix is a few days away as I write, and 30 years have passed since the most remarkable happening I have ever encountered in motor…