The most explosive motor racing rivalries

In a sport where there can only be one winner, it’s natural that rivalries develop when two different factions are battling to become top dog. The duel over the alpha male role has produced some of the most memorable showdowns in history, and also put many of the biggest personalities in the paddock on a collision course, often with spectacular results.

A note of caution: we have deliberately shied away from some of the well-worn clashes. Tales of the likes of Senna vs Prost and Hunt vs Lauda have been covered in such detail many times before that you won’t find them here. Nor will you read again about Ford and Ferrari’s battle for glory at Le Mans. Instead our run-down focuses on the less obvious – but just as explosive – contests that have shaped the sport.

25

Audi vs Peugeot

2007-2011

There was nothing odd about Audi’s Le Mans debut in 1999 – the race was awash with major manufacturers – but the company bucked the trend by introducing diesel propulsion from 2006… and winning. Peugeot followed suit one year later, its car a tad quicker on the straights, a fraction less efficient through the turns and similar in terms of lap time. The French firm would win only once, in 2009, but its presence added a partisan element that intensified the already vibrant atmosphere. If you witnessed any of Stéphane Sarrazin’s three consecutive pole laps, your neck hairs are probably still standing.

24

Nico Rosberg vs Lewis Hamilton

2013-2016

Friends and team-mates in karting, and bosom buddies in F3, they won the first two GP2 titles before graduating to motor racing’s top table… and friction only set in when they partnered up once more, this time in a potentially championship-winning team. Hamilton once suggested that his own modest upbringing made him hungrier for success than Monaco-bred Rosberg – odd, given that his hero Senna was hardly from an impoverished background – but Rosberg was more than a match at psychological warfare. He could not have dug any deeper to win his lone title in 2016; job done, he walked away.

23

Sébastien Loeb vs Sébastien Ogier

2011

Loeb was Citroën’s golden boy, Ogier the upstart that some observers considered an even finer prospect. Between them they won 15 consecutive WRC titles from 2004, but they had more in common than a forename – and their frequently parallel speed bred tension, particularly when they were team-mates. After the opening day of the 2011 Rallye Deutschland, PSA dignitary Jean-Marc Gales ordered that his two drivers hold station – with Loeb ahead. Ogier stopped sulking only when Loeb suffered a puncture that cost him the lead. It didn’t help internal relations when Ogier told reporters that he considered this to be “justice”. He left for Volkswagen soon after.

22

Carl Edwards vs Brad Keselowski

2009-2010

Brawls aren’t unusual in the top division of NASCAR, which can be a 200mph version of rugby league. The most celebrated blows were probably those exchanged by Cale Yarborough and Donnie Allison at Daytona in 1979, but here we’ll pick an enduring on-track feud between Edwards and Keselowski that began in 2009 and ran for more than a year – via several spectacular accidents, some of them deliberately triggered – until officials ordered the pair to calm down if they didn’t want to risk indefinite suspension. In the States, theirs is widely considered to be the most violent of all NASCAR rivalries.

21

Jim Clark vs Graham Hill

1962-1967

Before the advent of commercial pressures, duels tended to revolve around competitive friendships – a band of brothers travelling the globe and accepting the very real risks to which all were exposed. The preternaturally gifted Clark has always been recognised (quite properly) as one of the best there has ever been, Hill as one of the most determined. On his day, though, Hill was able to draw on improbable reserves of tenacity to match or even beat the Scot. You don’t win two F1 world titles, five Monaco Grands Prix, Le Mans and the Indy 500 by chance.

After Clark’s fatal accident at Hockenheim in April 1968, Hill went to the scene with Team Lotus’s mechanics to clear up the wreckage… and then set about helping to rebuild shattered morale, starting with victory in the next world championship race at Jarama. At the campaign’s end he was crowned for the second time, thereby matching the achievement of his fallen colleague. They had contrasting approaches, but emerged as serious title contenders at the same time – in 1962 – and kick-started a run of six British titles in eight seasons through the ’60s.

20

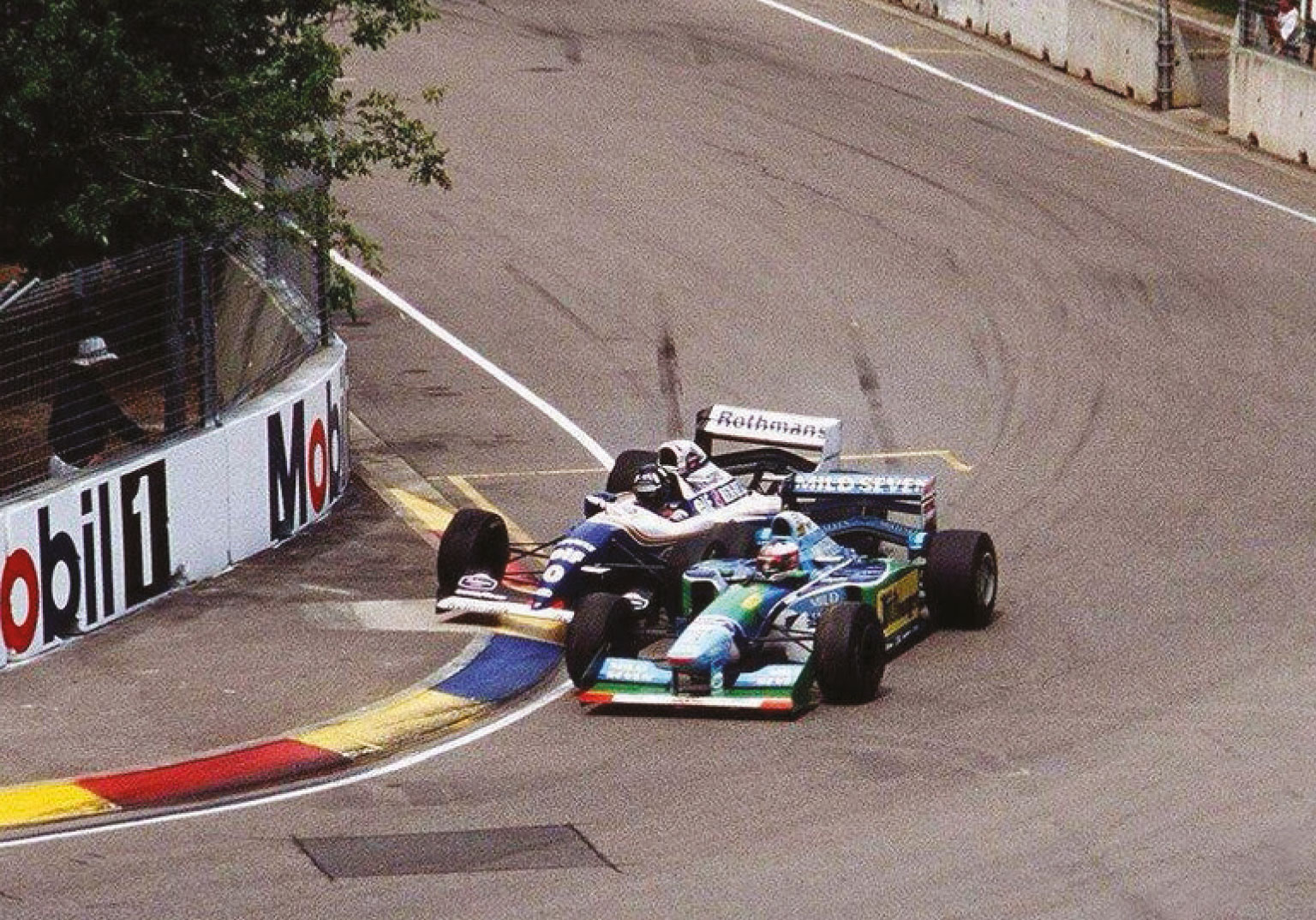

Damon Hill vs Michael Schumacher

1994-1996

Just as his father had been, Hill Jr was tasked with picking up a team that had lost its talisman. Following the death of Ayrton Senna at Imola in 1994, Hill notched up a victory for Williams two races later – in Spain, which might sound familiar. A strong run of form on his part – plus Schumacher’s exclusion from four events – set up a seasonal showdown in Adelaide… and the German resorted to a professional foul to secure his first title, clattering into Hill and putting both out of the race. On balance he was the rightful champion that year, but his methodology left a little to be desired.

19

Barney Oldfield vs Ralph DePalma

1908-1918

It’s said their mutual dislike began in 1908, after the unknown DePalma (left) got the better of the established Oldfield (top) in a three-part match race. Period reports imply the older driver stomped off without congratulating his conqueror, so bad sportsmanship isn’t just a modern thing. DePalma would win the Vanderbilt Cup (twice) and the 1915 Indy 500. When he filed a late entry for the following year’s Indy, the organiser had to seek the approval of every other driver before accepting. All but one granted their consent; no prizes for guessing who didn’t.

18

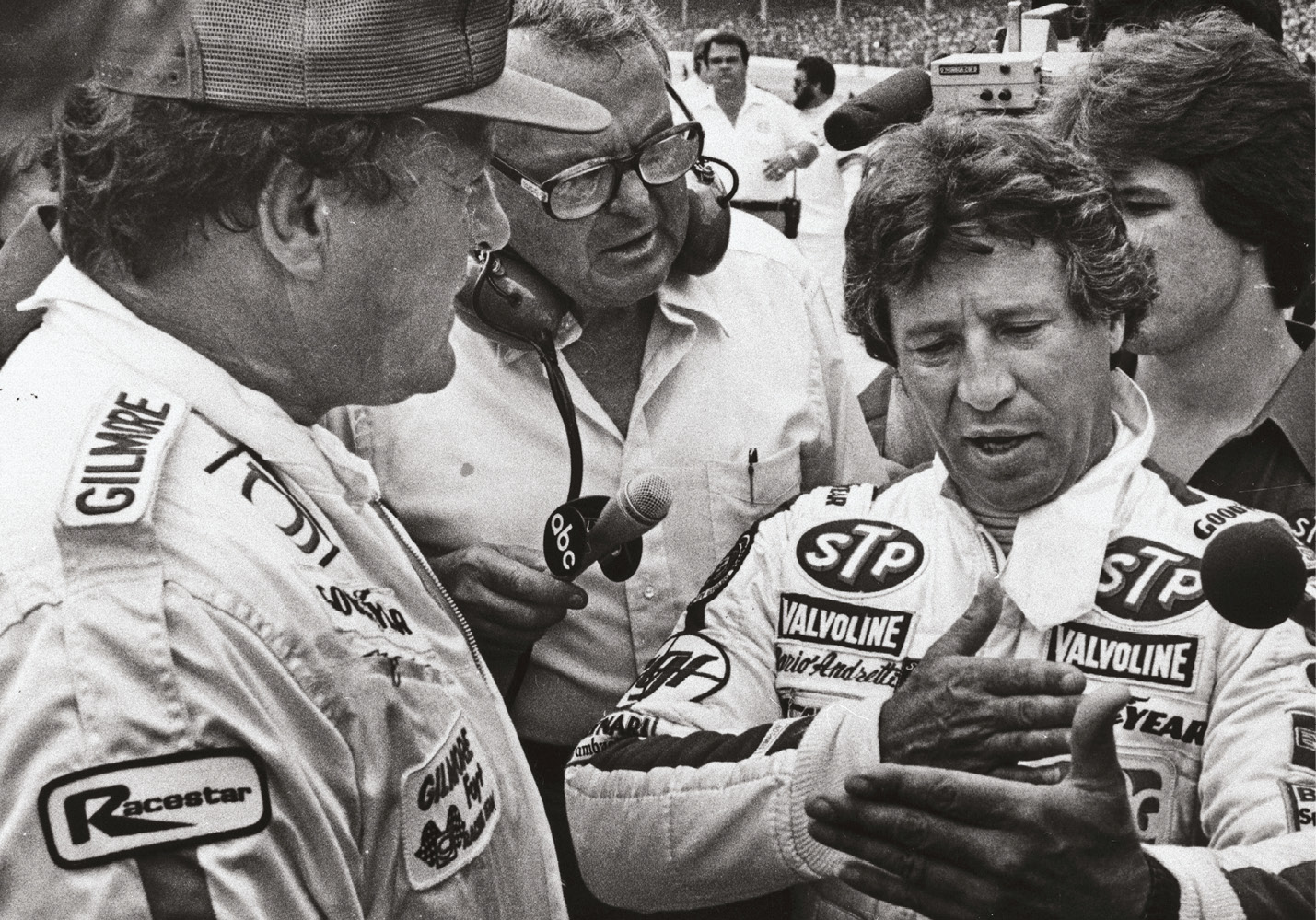

AJ Foyt vs Mario Andretti

1965-present

Both forged their reputations in the 1960s, Foyt winning his first Indy (of four) at the decade’s dawn and Andretti recording his only such success at its end. Versatility was a given – both scored NASCAR victories, Foyt won Le Mans, Andretti became F1 champion – but it was their enduring competitiveness in America that struck a chord. When Simon Taylor had lunch with Foyt (Motor Sport, Feb 2015), he received a glare after mentioning that he’d shared a burger with Andretti for a similar feature. As they ate, Foyt asked, “Better than Andretti’s burger, huh?” Probably time to let it drop, AJ…

17

Jason Plato vs Matt Neal

1997-present

Neal made his British Touring Car Championship debut in 1991, Plato in 1997: the former has won the title three times, the latter twice. They are part of the fabric of Britain’s top domestic series and, despite having a combined age of 104, there is no indication that either plans to retire just yet. Plato is no stranger to controversy – when he won his first BTCC crown in 2001, he did so after falling out with team-mate Yvan Muller (effectively costing Plato his seat at the year’s end, as Muller was under contract for two more seasons and Vauxhall had no desire to keep them both). His spats with Neal have been many, the most memorable coming during qualifying at Rockingham in 2011 (when both were fined £1000). When the session concluded, Plato gave his nemesis a traditional salute of displeasure and Neal reacted by grabbing his rival by the overalls, raising a fist and threatening to “rip his f***ing face off”. An unwise strategy, perhaps, given that Plato was still wearing his crash helmet at the time…

16

Nigel Mansell vs Nelson Piquet

1986-1992

Their mutual antipathy was apparent from the moment the Brazilian arrived at Williams in 1986. He’d won two titles to Mansell’s two grands prix, so considered himself number one – yet in equal kit Mansell was frequently the quicker. Piquet felt his set-up work benefited Mansell; it irked Mansell that Piquet was so precious about fine-tuning. Just get in the thing and race… A blown tyre in Adelaide cost Mansell the title in 1986; one year on he took eight poles and six wins to Piquet’s four and three, but the latter’s consistency made him champion. That didn’t exactly bring them any closer.

15

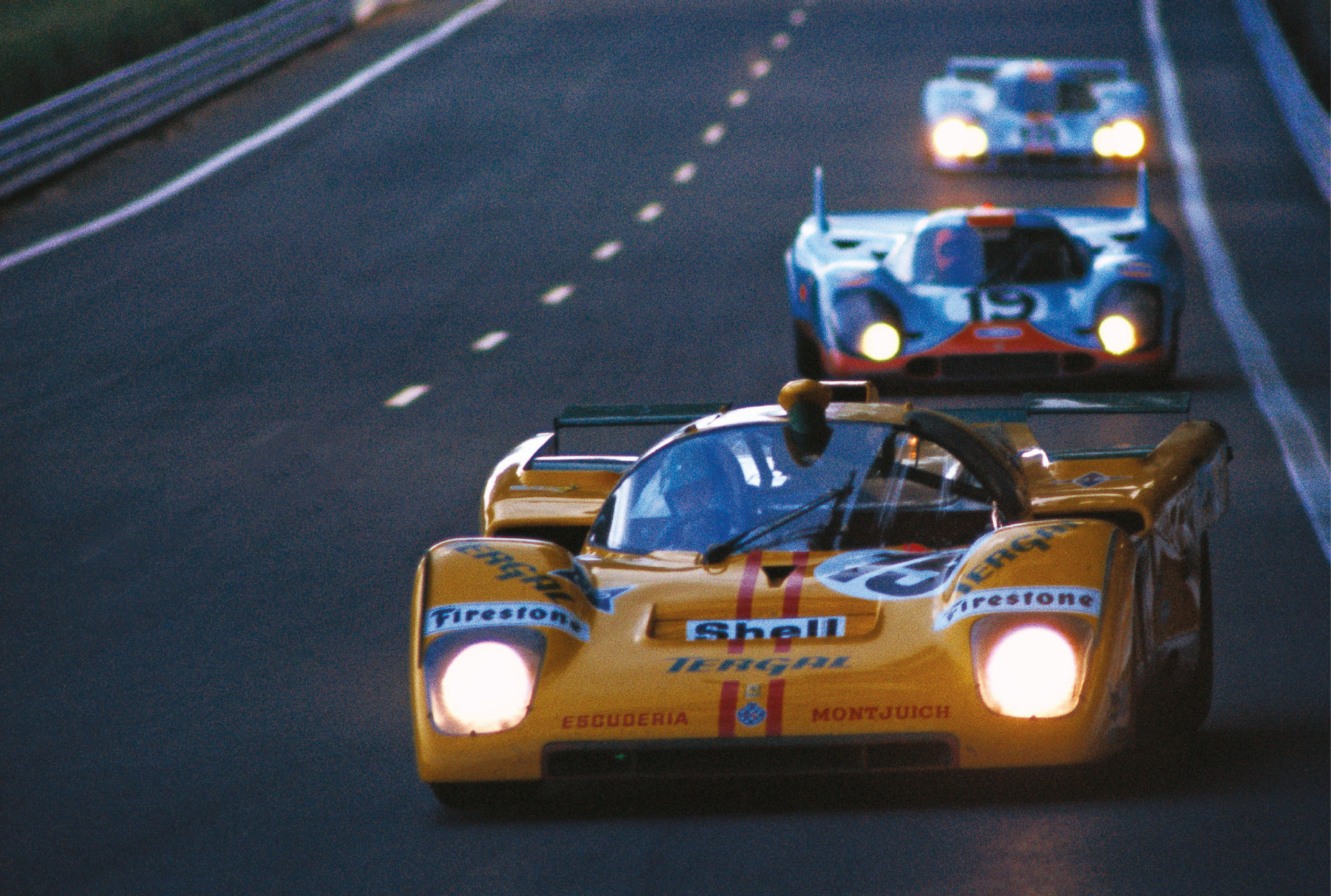

Porsche 917 vs Ferrari 512

1969-1971

Two of history’s most brutal – and beautiful – sports-prototypes, symbolic of a golden era for endurance racing. In truth, though, the 512S wasn’t quite match-fit when introduced, a little too heavy to challenge the finely honed 917 (also an unwieldy beast during its gestation). As Porsche dominated, Ferrari responded by developing the 512M (‘Modificato’), a trimmer version of its progenitor. That should have had the potential to rattle Porsche, but when a rule change was announced for 1972 (with a ban on 5-litre engines), Ferrari focused instead on building the 3.0-litre 312P and Porsche carried on winning. Usually, at least.

14

Tom Walkinshaw Racing vs The Automobile Club de l’Ouest

1993

Tom Walkinshaw was always happy to push regulations to their absolute limit – and was no stranger to controversy. Disqualifications, though, were rare. At Le Mans in 1993, the ACO insisted TWR’s Jaguar XJ220Cs should run with catalytic converters in the GT class, while the Scot argued otherwise. The team raced under appeal and David Brabham/David Coulthard/John Nielsen finished a class-winning 10th overall… until the ACO said TWR had not submitted its appeal on time and the car was excluded. It left its mark on Walkinshaw. As Brabham put it in a recent Motor Sport podcast: “Tom and the ACO hated each other”.

13

Carlos Sainz vs Colin McRae

1995

One field, two bulls. Their incendiary moment? The 1995 Rally Catalunya, when Subaru imposed team orders to permit a Carlos Sainz victory – yet the other party didn’t listen. Members of the team’s crew at one point had to resort to standing in front of Colin McRae’s car to slow him. That was the year’s penultimate event – and they went to the UK finale level on points at the top of the championship. Despite losing the Rally GB lead through delays (including having to straighten bent front suspension with a log), McRae looked irresistible as he fought his way back to the front. He went on to win by more than half a minute; Britain had its first World Rally Champion.

12

Ferrari vs McLaren

1976-present

Throughout the last part of the 20th century and into the 21st, McLaren and Ferrari gave each other no quarter. McLaren held the upper hand in 1998 and ’99, before Ferrari and Michael Schumacher fought back. But the team rivalry – which had been bubbling for decades – reached boiling point in 2007 with Spygate. The episode – which centred on an accusation that a disaffected Ferrari mechanic leaked top-secret technical data to his counterpart at McLaren – lifted the lid on the simmering distrust and animosity between the two fiercely competitive teams. In terms of results the Scuderia has won the constructors’ title 16 times to McLaren’s eight; the drivers’ title 15 times to McLaren’s 12.

11

Art Arfons vs Walt Arfons

1952-1966

Half-brothers with an aptitude for all things mechanical, they worked together on cars and bikes and even built their own aeroplane, but their destinies were shaped when they chanced upon an organised drag race in 1952. They built their own car and, as became custom, it consisted mostly of parts obtained from a scrapyard. It was named Green Monster – due to its colour – and that became the handle for all Art’s future creations.

History doesn’t record precisely what caused the once close-knit pair to fall out – Art’s overly competitive streak is often blamed – only that it happened in the late 1950s. They continued to build speed-record cars in adjacent Akron workshops, but without ever talking. During the early 1960s, both duelled with Craig Breedlove for the land speed record (Tom Green driving Walt’s Wingfoot Express) before Walt moved on to fresh pastures and left Art to pursue fresh records.

In 1966 the latter crashed at more than 600mph and initial reports suggested, incorrectly, that he had died. He was very seriously injured, however – and in time that led to a rapprochement of sorts with Walt. Their relationship would never again be as close as once it had, but they were at least back on speaking terms.

10

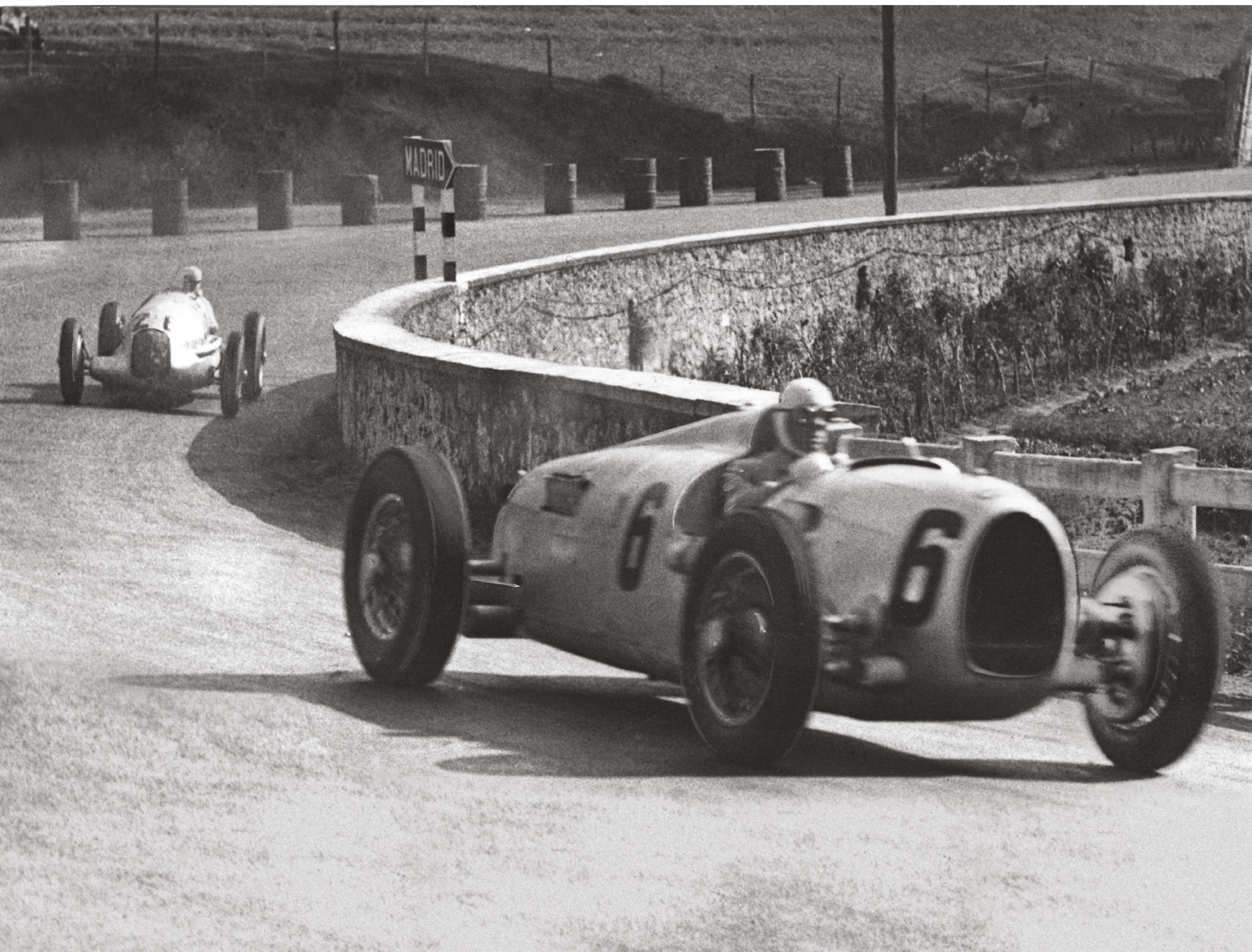

Mercedes vs Auto Union

1934-1939

The economic landscape wasn’t an obvious platform for a fertile grand prix era, with the effects of The Great Depression still felt and high unemployment in Germany. But Hitler’s National Socialists, keen to advance the home automotive industry, encouraged and funded firms to compete. In 1933 Mercedes and Auto Union – product of a merger between Audi, DKW, Horch and Wanderer – built cars for the new 750kg formula and the cocktail of technical freedom and funding raised racing to a new and sensational level.

From the W25 Mercedes developed the sleek W125 with its supercharged straight eight, then the V12 154. Auto Union campaigned novel but tricky rear-engined V16 cars, then a V12 and as the Silver Arrows duelled, shrieking blowers pushed power to 600bhp. From 1935-39 only German cars won a championship GP, barring Nuvolari’s exceptional 1935 French race – in an Alfa with 100bhp less. Silver specials took impressive speed records, too. The British, meanwhile, were pottering about in ERAs.

9

Don ‘Snake’ Prudhomme vs Tom ‘Mongoose’ McEwen

1964-1973

Away from the drag strip they were mates – and a shared deal with Mattel’s Hot Wheels toy car brand, negotiated by McEwen, generated useful cash, introduced them to a younger audience and made both household names in the States. On the track they were fiercely, enduringly competitive. Prudhomme was the quiet one, who would sit impassively during pre-event publicity interviews while McEwen shouted about how he was going to prove who was boss come race day. It was Prudhomme who recorded the first five-second pass for a Funny Car and won four straight world titles, but there was seldom much between them.

8

Turbos vs natural aspiration in F1

1977-1989

With a few exceptions (Ligier’s wailing Matra V12, the glorious flat-12s of Ferrari and Brabham-Alfa Romeo, the hopeless BRM V12 that might have been more effective as a yacht anchor), F1 was ‘Planet Cosworth’ in 1977. Of the 32 teams that attempted to qualify for at least one grand prix that season, 27 ran Cosworths. But then came Renault, with a 1.5-litre V6 turbo evolved from its sports-prototype engine.

It smoked, rattled and, more often than not, blew up. But Jean-Pierre Jabouille nursed the car to a first finish at Monaco in 1978, scored points in America and won the 1979 French GP. Reliability was patchy, but Ferrari (and Toleman) went turbo in ’81 and two years later Nelson Piquet (Brabham-BMW) became the first driver to take the title with a turbo car. When Michele Alboreto won the Detroit GP for Tyrrell on June 5 1983, it would be the 155th and final victory for the Cosworth V8 – and the last for natural aspiration until 1989, by which stage turbos had been banned.

7

Kevin Schwantz vs Wayne Rainey

1986-1993

Their paths first crossed in 1986, racing Superbikes in their native America – and there was more than a frisson of friction. Speaking to Motor Sport’s Mat Oxley (Jan 2013), Schwantz said, “I don’t know why I disliked him, except that I knew how much he disliked me. So I figured I’d dislike him just as much…” They went on to commence their grand prix careers at the same time, two years later, and Rainey won the world title in 1990 – the first of three on the trot for Yamaha. For ’93, however, Yamaha hadn’t perfected its chassis set-up and Schwantz’s Suzuki was now a match, a detail underlined by his victory in the season-opener at Eastern Creek, Australia. Rainey bounced back to win at Shah Alam and Suzuka (by 0.08sec!) before the pendulum swung again. After the 11th of 14 rounds, at Brno, each had four wins – and Rainey held a slim points cushion. While leading the next race at Misano, however, Rainey fell heavily and suffered paralysing injuries. Schwantz went on to take the title, but Rainey’s absence had diluted his zest for competition. He would score just two more wins before retiring.

6

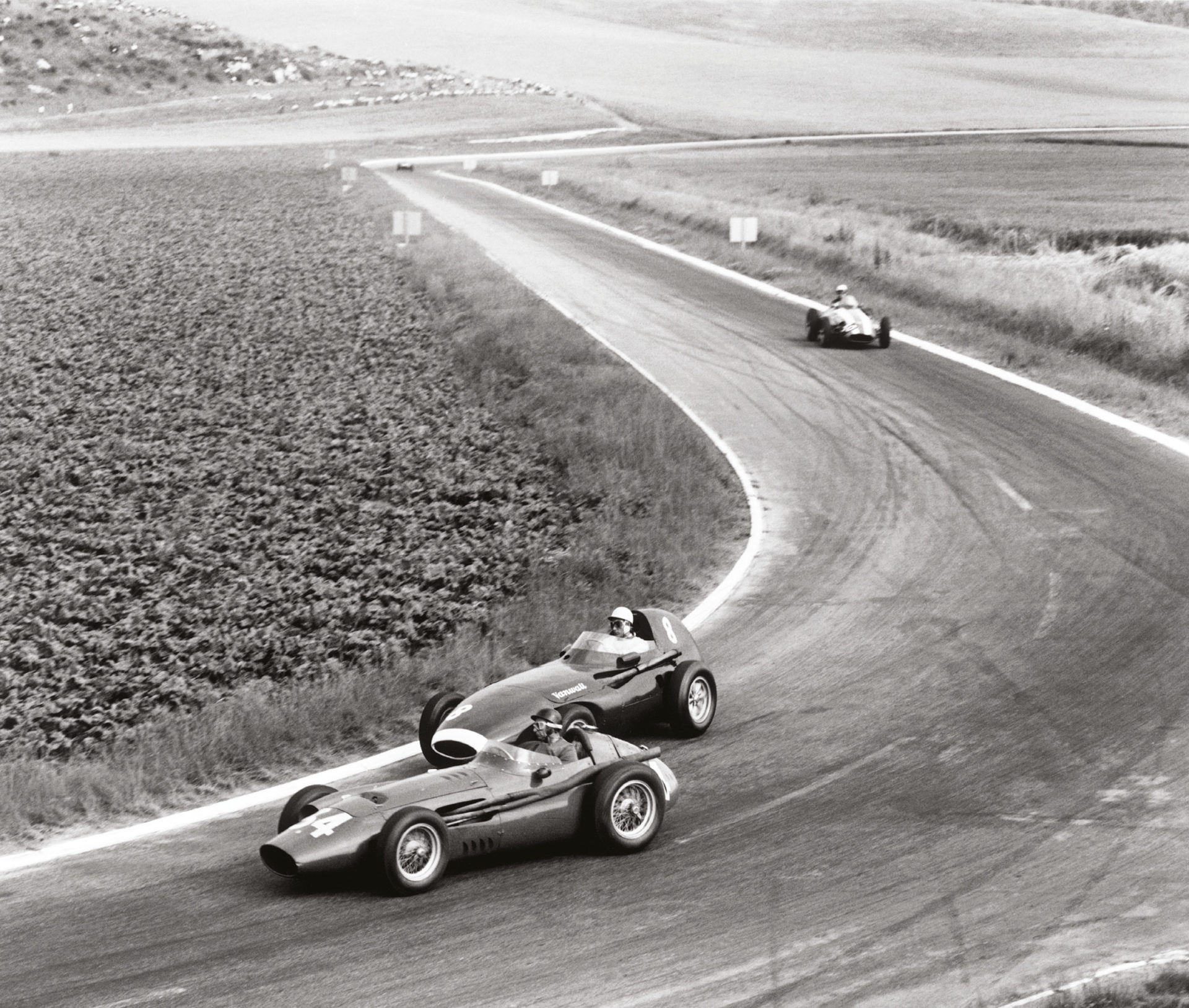

Britain vs Italy

1950-today

Many manufacturers’ reputations had been forged during the pioneering days of international racing, when the likes of Renault, Delage, Mercedes, Duesenberg, Bugatti, Peugeot, Sunbeam, Talbot and OM recorded significant victories. Alfa Romeo had emerged simultaneously – and, with compatriots Maserati and Ferrari, was at the forefront when the sport dusted itself off after WWII. When the world championship began in 1950, Italian cars dominated everything bar the Indy 500.

No other nation won one of the conventional grands prix until France 1954, when Mercedes joined in for a successful two-season spell. Thereafter Ferrari and Maserati continued to paint the track red until Vanwall began winning races in 1957. Italy had dominated the decade, but when the championship for constructors began in ’58, Vanwall became the inaugural recipient. Cooper was by now also on the map, having scored two victories with its mid-engined curios, and teams like BRM, Lotus and Brabham would become successful within a short space of time. The look of the cars was changing – and so was the seat of power. Alfa Romeo has not won a race as a constructor since Spain 1951; no Italian driver has been crowned since Alberto Ascari in ’53.

5

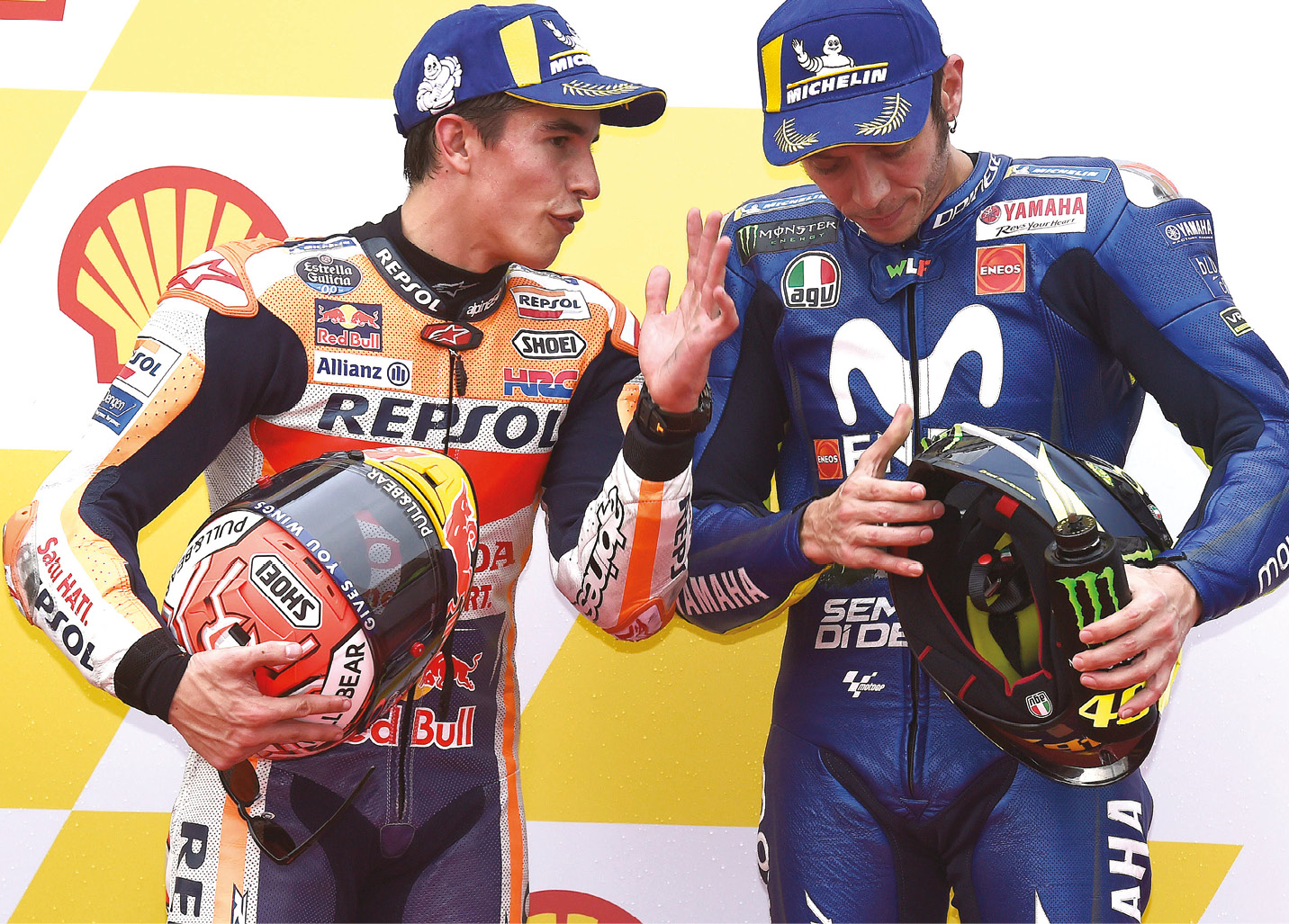

Valentino Rossi vs Marc Márquez

2013-today

Rossi stepped up to motorcycle racing’s top table in 2000, Márquez 13 years later (by which time the Italian had seven premier-class titles to his name). At first the two were all smiles; Rossi had been Márquez’s idol and the former seemed to see something of his younger self in the Spaniard, whose style brought not just a knee to the track but also a shoulder. But then competition between them intensified and the relationship descended into verbal and psychological warfare. During the 2015 Malaysian GP, Rossi raised a knee and forced his rival to crash out. Those smiles had long since vanished by that point.

4

John Surtees vs Eugenio Dragoni

1964-1966

Dragoni was Ferrari’s sporting director, Surtees the seven-time motorcycling world champion who’d switched seamlessly to cars and earned a Ferrari drive on merit. Dragoni, though, seemed to resent his presence, to the extent that he protested his own winning car at Sebring in 1964 – that of Surtees and Ludovico Scarfiotti – in a bid to secure victory for its sister entry. That failed. At Le Mans in 1966, against the might of Ford, Surtees felt he should take the start to maximise Ferrari’s chances; when Dragoni refused, nominating the worthy but slower Scarfiotti, Surtees left the track, drove to Maranello and handed in his notice.

3

Brabham vs The Paddock

1978

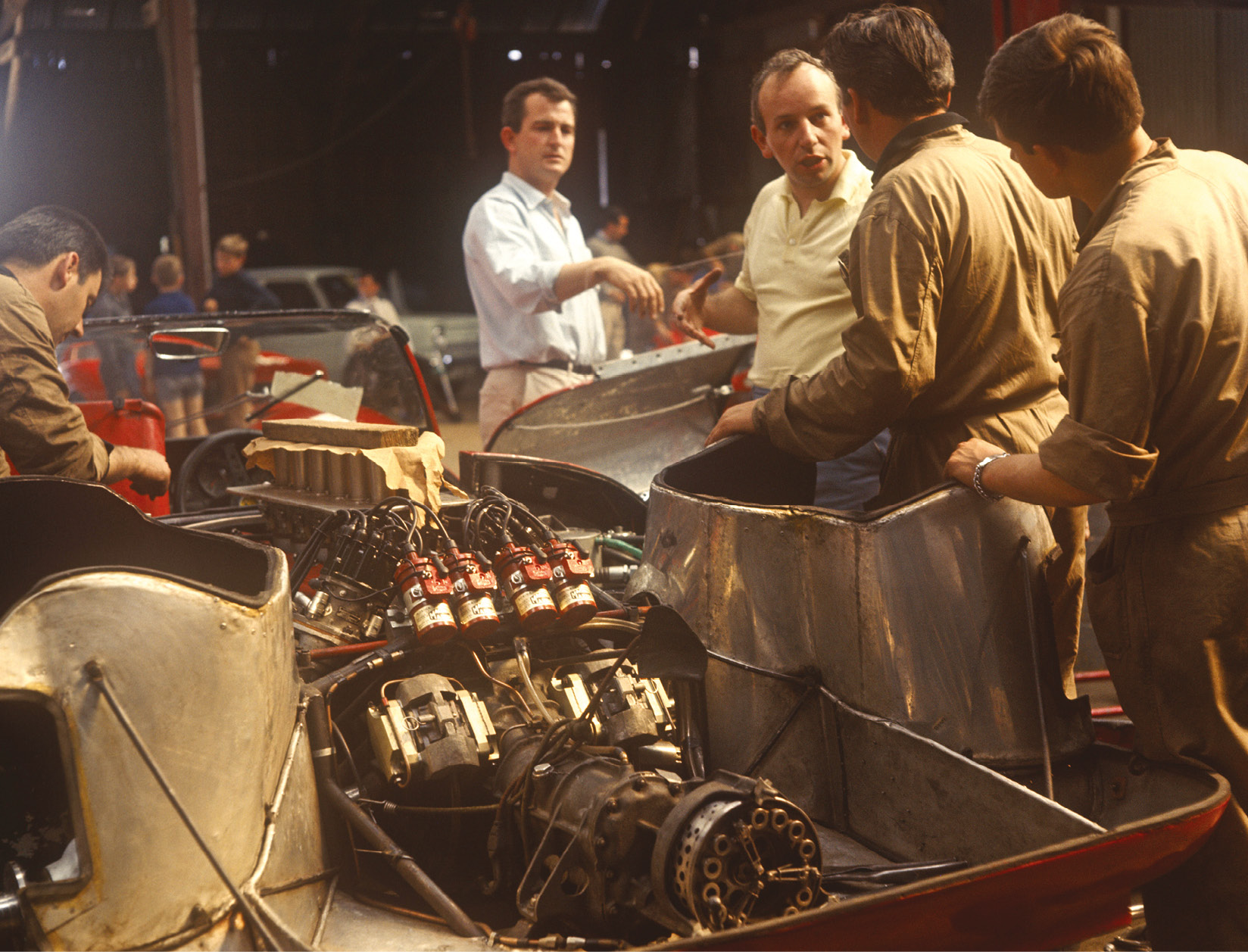

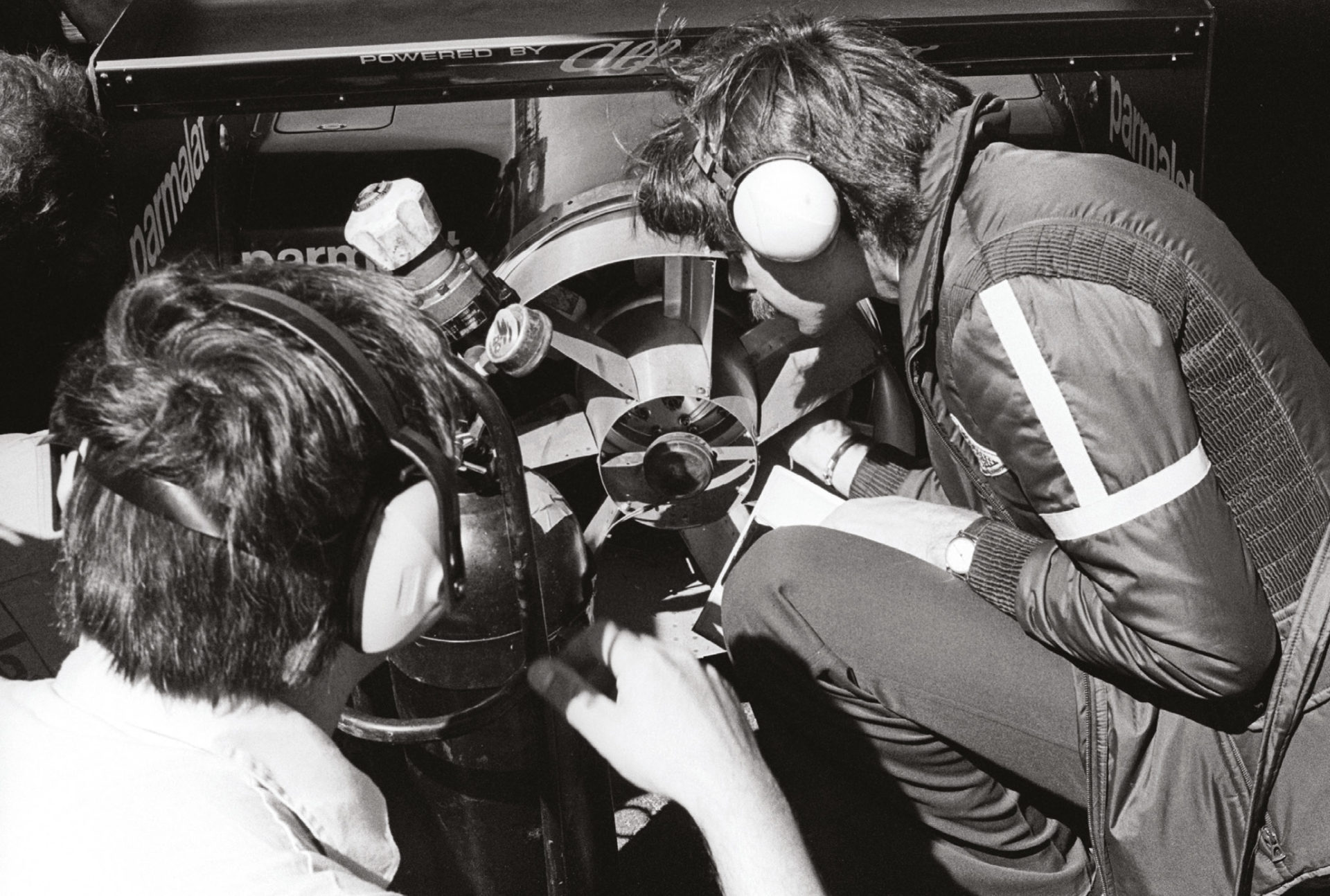

It was an idea that occurred to Brabham designer Gordon Murray in the bath. Wings had been bolted to F1 cars during the 1960s, but serious aerodynamic progress began to be made the following decade, when Colin Chapman introduced his ground-effect Lotus 78 and improved it significantly with the following 79, which carried Mario Andretti to that season’s world title.

In a bid to find some way of matching the levels of downforce that Lotus had, Murray imagined the Brabham BT46B, or ‘fan car’.

It featured a radiator mounted horizontally over the engine and cooled by a vast, gearbox-driven fan at the rear. The car featured flexible skirts, so the fan fed the radiator with air and quite literally sucked the car to the track. Brabham team boss Bernie Ecclestone suggested his drivers take things easy in qualifying for the 1978 Swedish GP and they lined up second and third, John Watson ahead of Niki Lauda, but both more than half a second adrift of Andretti… largely because they ran heavy with fuel.

“Andretti claimed the car was projecting stones at other cars, which it wasn’t. It was legal.”

Amid much bickering from rivals, Lauda won by more than half a minute. “Andretti claimed the car was projecting stones at other cars, which it wasn’t, and it was legal as the rules stood,” said Murray. “I had to ensure that over half of the air was cooling the radiator. After the race the FIA came to the factory and measured the flow of air through the fan and through the radiator. I’d worked out that 55 per cent of the air was for cooling and 45 for downforce, but they said it was 60/40.”

The FIA confirmed the car’s legality, but also underlined that the loophole Brabham had exploited would be closed for 1979. But the BT46B had won its first, last and only race.

At the time, Ecclestone had his eye on establishing a power base through the Formula One Constructors’ Association – and for that he needed the support of such as Chapman, Ken Tyrrell and the other team owners who had been upset by the BT46B.

Speaking to us for Lunch with (Motor Sport Jan 2008), Murray said: “I didn’t understand this at the time, but Bernie had his eyes on bigger things. He was working on getting his foothold in FOCA and launching himself towards what he did later. He reckoned the uproar was in danger of collapsing FOCA completely. So he asked me – he didn’t dictate – to fit normal radiators to the car. I was very pissed off, but I agreed.”

Contrary to popular perception, the car was never actually banned.

2

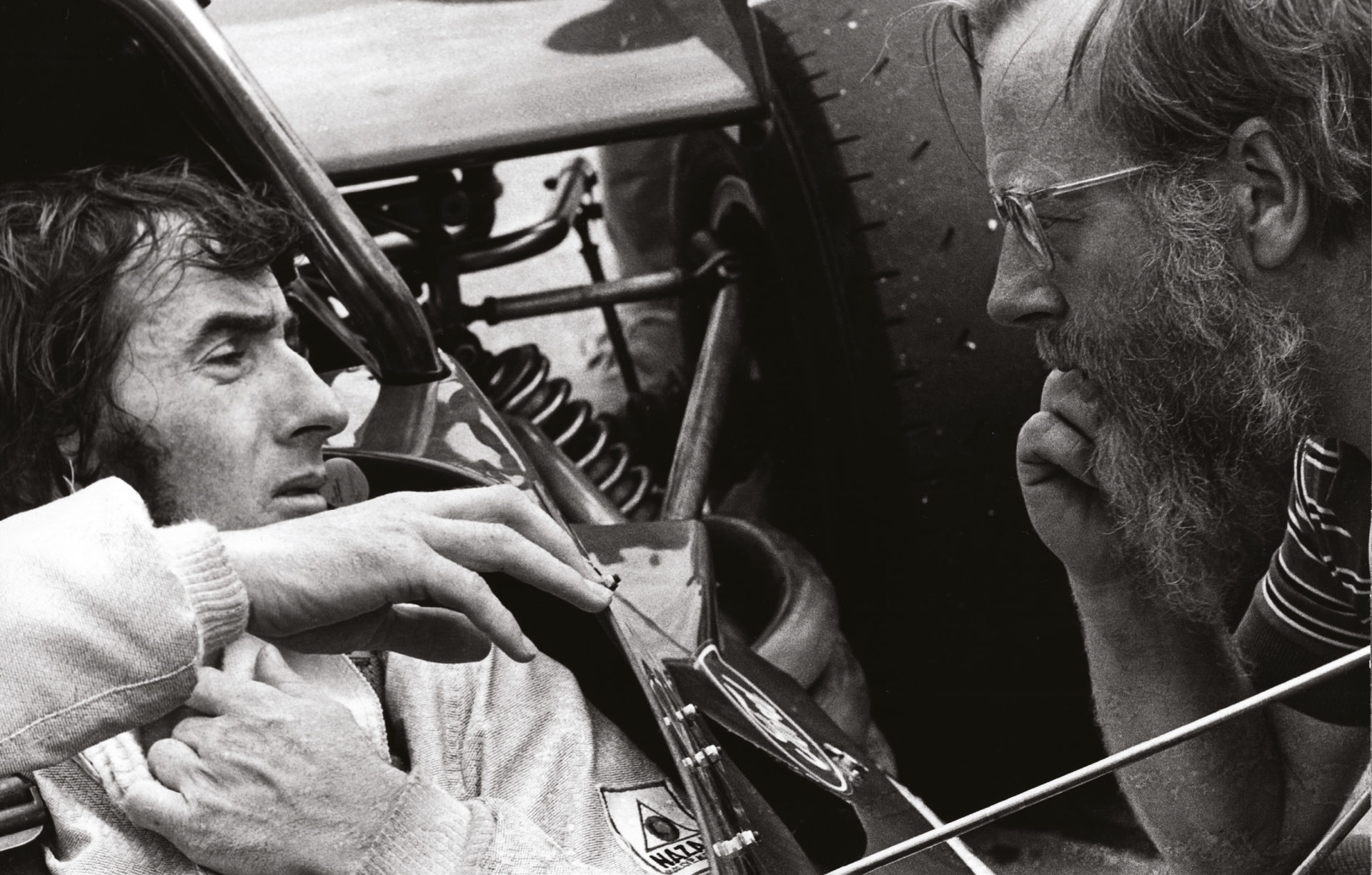

Jackie Stewart vs Denis Jenkinson

1972

“You’d see him there,” says Jackie Stewart, smiling about it in retrospect, “a small figure, close to the Masta Kink, and think, ‘Oh no, Jenks’. You knew why he was there and think to yourself, ‘Better make sure I take it flat next time’. And you had a full lap of the old Spa to think about that…”

Back in the day, though, Stewart and Motor Sport’s own DSJ were overtly opposed to each other’s ideals. Jenks was no shrinking violent. He was passenger to inaugural sidecar world champion Eric Oliver in 1949 and, perhaps more famously, served as Stirling Moss’s navigator during their extraordinary victory on the 1955 Mille Miglia. He was strongly opposed to the notion of the sport moving away from its traditions and embracing “standardised, characterless autodromes”.

Stewart, in contrast, felt too little was being done to protect drivers. Cars were getting faster and circuits weren’t adapting to accommodate rising speeds. Stewart played his part in steering F1 away from both the Nordschleife (for 1970, at least) and the original road circuit at Spa. He admits this made him “very unpopular”.

In Motor Sport June 1972, Jenks let rip. “Before the Sebring 12 Hours a certain beady-eyed little Scot was going around drivers encouraging them to sign a GPDA petition calling for a boycott on all F1 or FIA Sports Car Championship races at Spa.

“Can you really ask me in all honesty to admire, or even tolerate, our world champion?”

“I frequently receive letters from readers who ask why I keep attacking Stewart and his GPDA; surely the reason is becoming all too clear. If he said, ‘I had a nasty experience at Spa in 1966 and have no intention of going there again’ I would accept his feelings. But it is not as simple as that. His pious whinings have brain-washed and undermined the natural instincts of some young and inexperienced newcomers to grand prix racing and removed the Belgian GP from Spa. I will admit that grand prix racing is his life and he has every justification in anything he does concerning that, but WHAT HAS LONG-DISTANCE SPORTS CAR RACING GOT TO D0 WITH STEWART? To the best of my knowledge he has never been a serious competitor. Can you really ask me in all honesty to admire, or even tolerate, our current world champion?”

In the August issue, Stewart hit back: “I devote considerable time and effort to make motor racing safer for as many people as possible – officials, spectators, drivers and even journalists. It is very easy to sit on the fence and criticise. You can always find faults in what other people are doing, but at least they are doing something. All Mr Jenkinson seems to do is lament the past and the drivers who have served their time in it. Few of them, however, are alive to read his writings.

“There is nothing more tragic than mourning a man who has died under circumstances that could have been avoided. It angers me to hear people who oppose an effort to make our sport safer… Such men to me are hypocrites, the only consolation being that in years to come they will be looked back on as cranks.”

Slightly spicier than modern F1.

1

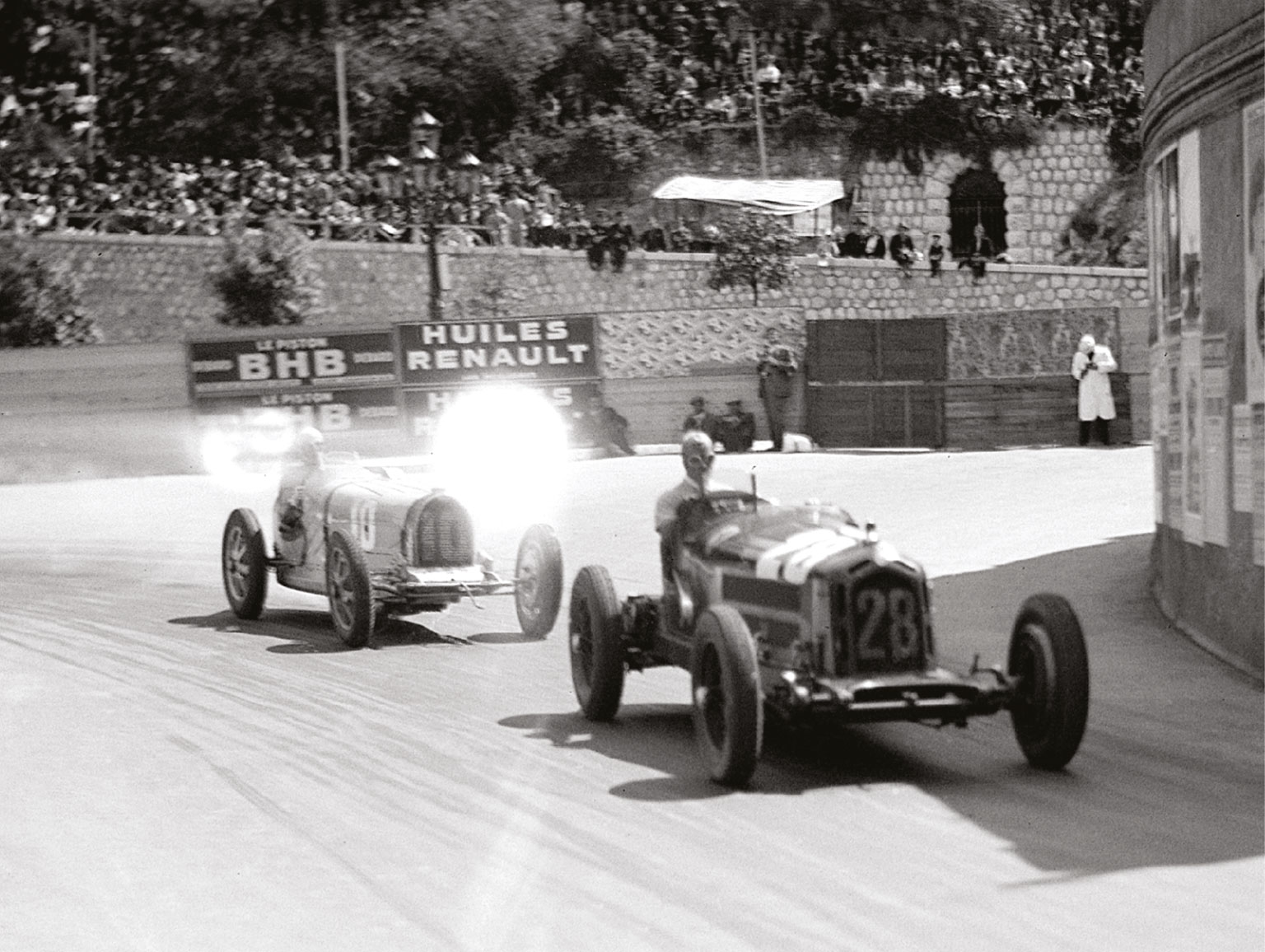

Tazio Nuvolari vs Achille Varzi

1930-48

A relic from an age long before social media or even TV, Nuvolari was a prototype John Surtees, if you like, a serial motorcycle racing champion who found cars suited him just as well. You don’t always see him referenced when the sport’s ‘greatest of all time’ are discussed, a reflection of the shadow in which motor racing existed during his day, but when Mark Hughes attempted to unravel that very topic for Motor Sport (Nov 1999), he placed Nuvolari at number one – and Ferdinand Porsche, founder of the car company, is said to have described Nuvolari as “the greatest driver of the past, the present and the future”.

That is the context in which Varzi (12th on the Motor Sport list) should also be judged.

Nuvolari was apparently a man bereft of fear, a blend of showman, daredevil and thinker, somebody able to temper his natural instincts with the mechanical sympathy required to pull off improbable feats. How else could he have defeated the combined might of the Silver Arrows in the 1935 German GP? It was more impressive still that he beat them four times in major races the following season, when the German cars were getting ever better, the Alfa ever older. He remained loyal to Alfa until the start of 1938, when a split fuel tank during the Pau GP persuaded him that his future lay elsewhere. Next stop: Auto Union. If he could no longer beat them…

“Ferdinand Porsche said Nuvolari was ‘the best driver of the past, the present and the future’”

The son of a wealthy textile manufacturer who also cut his teeth (successfully) on two wheels, Varzi was by then fading, his focus having been deflected by morphine addiction and an affair with the wife of fellow racer Paul Pietsch. At his peak, though, he had been Nuvolari’s closest adversary, fuelled by the same competitive will yet calmer in his delivery – a Prost to Nuvolari’s Senna.

Their most celebrated contest? Perhaps the 1930 Mille Miglia, when Varzi felt sure he was leading – that was the information coming from the time controls as he headed back towards Brescia – until his nemesis nipped past. Legend has it that Nuvolari had kept his Alfa’s lights switched off during the darkness of early morning, so that Varzi would be less aware of his approach.

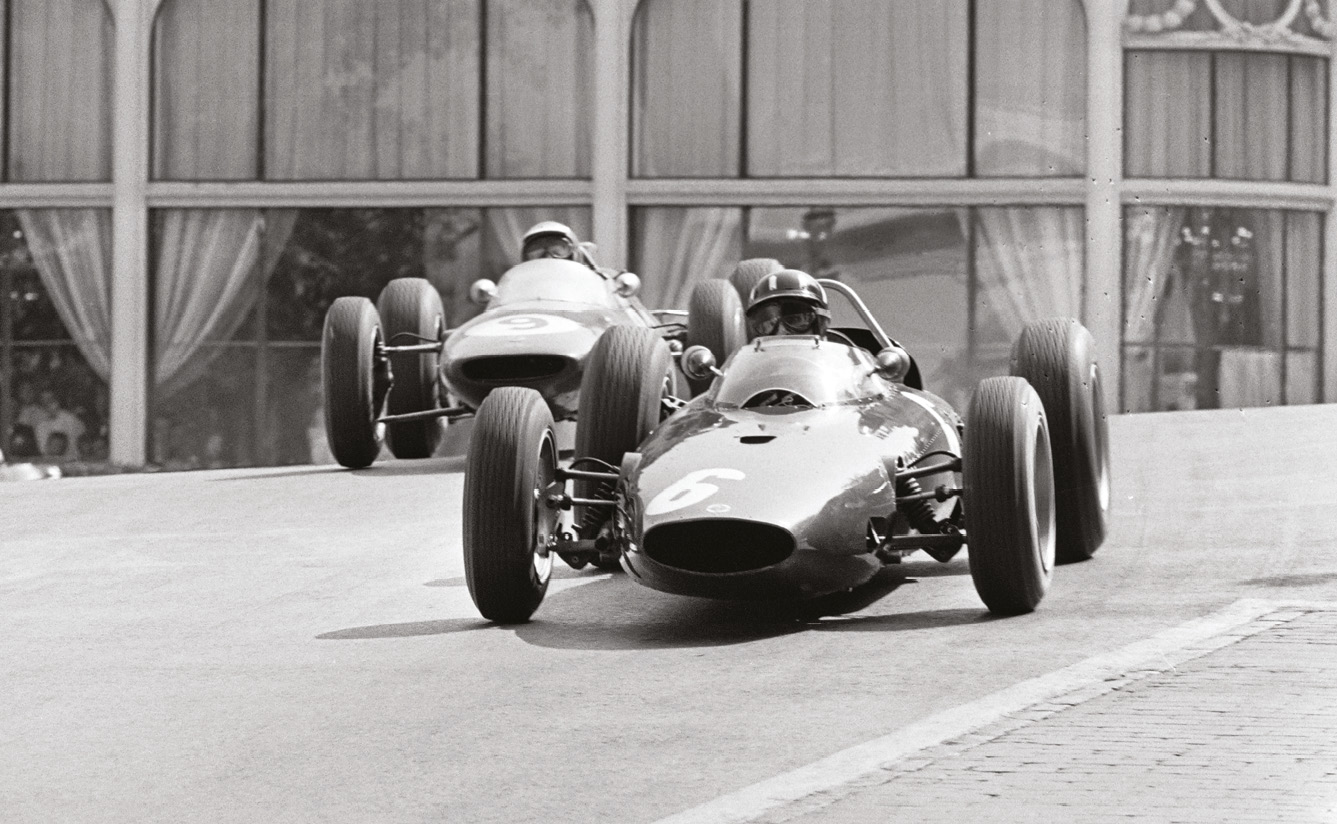

That, though, had been a race against the clock. In terms of wheel-to-wheel ferocity, the 1933 Monaco GP perhaps showcased their contrasting yet similar talents to fuller effect. Varzi took pole in his Bugatti T51, with Nuvolari fourth on the grid in his Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Monza. The latter was soon through to second and the pair swapped the lead continuously. Varzi had a more agile chassis, Nuvolari better acceleration.

On the final lap, Varzi risked his engine by holding third gear for longer than usual to take the lead and Nuvolari’s ability to respond was scuppered by piston failure. They had been locked together for all bar three of the 100 laps, but Varzi was able to drive relatively gently towards the finish as Nuvolari jumped out and tried to push his car to the line. When a mechanic lent a hand, he was disqualified.

His gesture underlined a refusal to accept defeat that was common to both. Having cheated death many times, Nuvolari’s health deteriorated after WWII – not least due to asthma, brought on by years of inhaling exhaust fumes. He made his last competitive start in 1950, winning his class in a hillclimb, and died in 1953 following a stroke.

Now in his 40s, and having sorted out his personal life, Varzi returned to racing after the war. Having very rarely crashed during his racing pomp, he was killed while practising for the 1948 Swiss GP at Bremgarten.