Anthony Joseph Foyt II was born in Houston 80 years ago, and grew up in a tough area called The Heights – “so tough people locked their car doors when they drove through it. Right from a kid you learned to take care of yourself, or someone’d beat the shit out of you.” His father Tony had a garage with an old Air Force friend, Dale Burt, and both of them raced on the local dirt tracks on Friday and Saturday nights. As soon as he could walk AJ became a keen member of the team, and when he was five his father made him a little lawnmower-powered racer with which he wore a groove in the yard.

When he was 11, one evening when his parents were out, AJ got his daddy’s Ford V8-powered Midget racer off its trailer. He climbed aboard and was roaring around the back of the Foyts’ little two-room bungalow when a blow-back through the carburettor set the car on fire. He tore off his shirt and smothered the fire with little more than blackened paint for the car, but badly burned hands for AJ. “But I reckoned my ass was goin’ to hurt worse when my daddy got home.” He got the racer put away, and when his parents returned he was in bed with his eyes tight shut. His father wasn’t convinced, but maybe he’d resigned himself to his boy being a race car driver, because nothing more was said.

AJ was driving his friends’ cars before he was legally old enough, and as soon as the licence came he bought an ancient Oldsmobile, and hopped it up within an inch of its life. Having worked on Tony’s and Dale’s cars, he was already a very good mechanic. He challenged his pals on the local roads, and they also broke into the local Arrowhead track at night and raced there under cover of darkness. Stories began to filter back to Tony, and he told AJ he had to stop racing on the street “or he’d whup my butt.”

“I decided logarithms and Wordsworth weren’t going to help my racing career, so I quit school, found a 1939 Ford coupe for 100 bucks and built it up into a stock car. My first race was on dirt at Playland Park.” He learned fast, and the wins started to come. Next he talked his way into a borrowed Midget, an old and uncompetitive car, and put on such a hairy sideways show keeping up with the newer machinery that his dad and a friend scraped together $800 for a decent Kurtis Midget chassis. Its four-cylinder Offy engine came from the wreck of a friend’s fatal crash. “Those little engines had about 100 horsepower, so they went pretty good.”

And AJ went pretty good, too. In his first outing he won everything: the initial Trophy Dash, then his heat, then the semi. In the final he fought past local hero Tommy Rackley to win that too – although it was an elbow-to-elbow battle, and Rackley wanted a fist fight in the paddock afterwards.

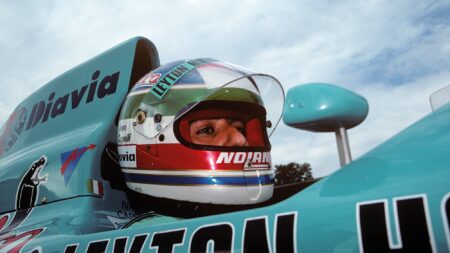

Celebrating a fourth Indy 500 success in 1977

IMS

In those days jeans and an oily T-shirt were a driver’s normal race wear, but now AJ was racing in red silk shirt and immaculate white pants. “I wanted the car and me to look smart. I had no money, the few dollars I won I put back in the car. I kept just back enough to eat. I’d sleep in the towcar or, if the weather was dry, on the ground. I was the cheapest racer around.” All over Texas, into Louisiana and Oklahoma, the teenage Foyt became the man to beat. It was a school of hard knocks: after one race a guy punched him while he was still in the car. “I couldn’t get to him, so Daddy beat the hell out of him.” There was cheating, too. “Guys would punch out their engines [increase their capacity] but every time my engine was protested I’d say, Go ahead, pull it down, I don’t care. They always found it was legal.”

In 1955, now 20, AJ used his prowess in Midgets to wangle rides in the bigger Sprint cars, and started to go further afield. St Paul, Minnesota, 1200 miles from Houston towards the Canadian border, was called the Indianapolis of Sprint car racing. Against a 60-strong entry, AJ qualified on pole and won the race. There was a fight after that one, too, but even though AJ was outnumbered by the locals he gave as good as he got.

“As well as Sprint cars I was still driving Midgets, Stock Cars, anything I could get into. Wally Meskowski gave me some Sprint car rides, and that got me noticed some more, and in 1958 I got my first ride in the Indianapolis 500, in the Dean Van Lines Special run by Clint Brawner. Because I was the new guy Pat O’Connor, who’d had the pole the year before, offered to lead me around for a few laps. He was really good to me. I had to do my rookie test: 10 laps each at average speeds of 120, 125, 130 and 135. It had to be just right, one mistake and you were out. Did that, and then I started to work away to find my groove. At Indy all four corners are completely different, you have to learn the characteristics of each. And how the wind was blowing was much more of a factor than later, when ground-effects came in. The track felt big and the car felt big.” The youngest driver there, AJ averaged over 143mph to qualify 12th fastest.

The race started in the worst possible way. “The drivers tell you, watch for the draft, watch for this, watch for that, then everybody’s crashing, what the hell do you watch for now?” On the first lap front row men Dick Rathmann and Ed Elisian touched, and started a 15-car accident that ricocheted down the field. AJ’s new friend Pat O’Connor, from the middle of row two, was caught up in it, and his car cartwheeled into the air, landed upside down and burst into flames. O’Connor was incinerated inside. Foyt, from row four, spun to avoid the carnage, and managed to drive on. “I come round next lap and Pat’s burning there. I say to myself, AJ, is this tough or not? I raced on, and after 400 miles I had a water hose break in Turn 1, spun on my own water but missed the wall. That was me done, but they gave me 16th place. That was my first Indy.”

What almost defies belief is that AJ was still racing at Indy 34 years later. In those three and a half decades racing car design changed out of all recognition. He started as a young charger in the big solid-axle front-engined Offy roadsters, and he was still a charger in the rear-engined monocoques with multi-cylinder, multi-cam turbocharged engines and ground-effect aerodynamics. His wins spanned the generations: he was a great racer in the Fifties and a great racer in the Nineties.

For Indy in 1959 rollover bars and fire suits became mandatory, but Jerry Unser and Bob Cortner both died in practice. AJ qualified 16th after blowing an engine, got up to fifth, then more problems dropped him to 10th.

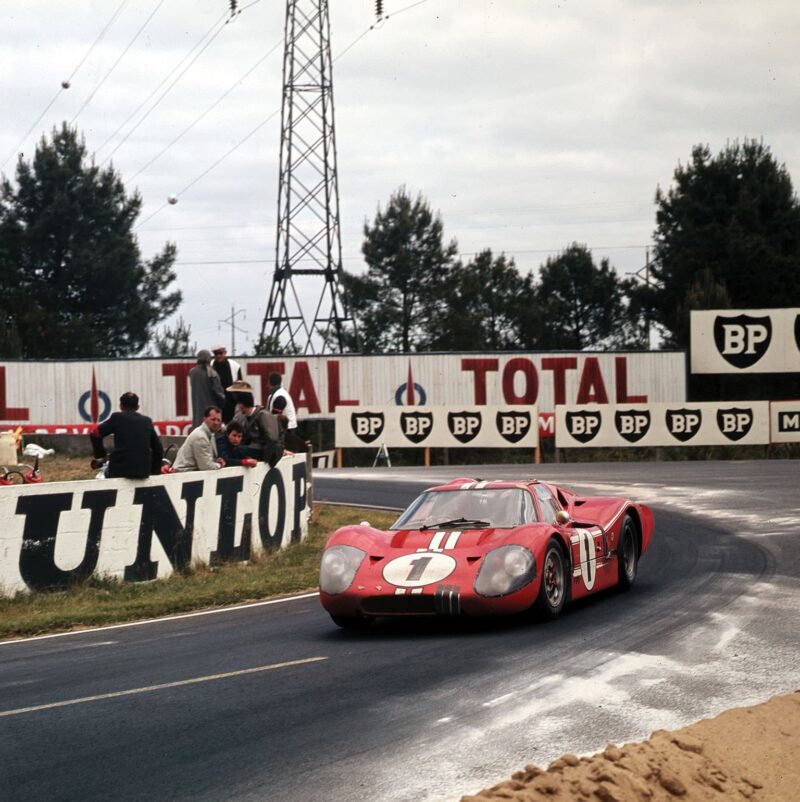

Le Mans success with Dan Gurney in 1967

Motorsport Images

That year he travelled out of the US for the first time, to Italy for the Race of the Two Worlds. “The high Monza banking was unbelievable. We were doing 175 around there.” AJ took over the Kuzma-Offy that Maurice Trintignant had started and finished sixth, despite breaking his crank before the end.

Double USAC champion Jimmy Bryan, who’d won AJ’s first Indy in 1958 and also the first Monza Two Worlds race, finished second that day. “Jimmy always raced with a cigar butt in his mouth. In 1960 he retired after a 10-year career, but the Langhorne promoter paid him a lot of dollars to come back and do one last race. Jim Hurtubise was on pole, Jimmy qualified second with me third. From the start we went into Turn 1, Bryan went end over end and was killed. I won the race.”

By 1960, his second full year in the top USAC category, AJ had started a successful but often stormy working relationship with legendary engineer George Bignotti. At Indy a blown clutch ended his race, but thereafter things came right. AJ won four of the last six races of the season, and took the title from under Rodger Ward’s nose. At 25, he was USAC champion. He would be champion again three times in the next four years, and seven times in all.

The longed-for Indianapolis 500 victory came in 1961 – and there was a surprise in the paddock. AJ said later: “We all think green is a bad colour. You don’t wear green socks, or drive a green hire car. And this guy turns up with a green race car. If that wasn’t enough, the son of a bitch had its engine in the back.” Another Indy wag described the visitors as “Guys with college degrees who didn’t know their ass from their elbow.” But Jack Brabham’s Cooper-Climax started 13th and finished ninth, and quietly sowed the seeds of a revolution.

Indy started badly that year when 1958 USAC champion Tony Bettenhausen offered to try Paul Russo’s car in practice to help sort its tricky handling. “He told them to put more castor on. They took a bolt out to adjust it and didn’t put it back in tight. Going down into Turn 1 the suspension came apart.” In the ensuing fatal accident the car wrapped itself up in a length of steel wire fencing. AJ counted Bettenhausen as another friend, and when he heard the news he threw his helmet across his garage in fury. Then he picked it up and got back in his car.