“In Formula 1 we don’t pass on the outside!” Hunt raged afterwards, and I mentioned this to Andretti. “I got news for him,” Mario growled. “Where I come from, we pass outside, inside, every goddam side…”

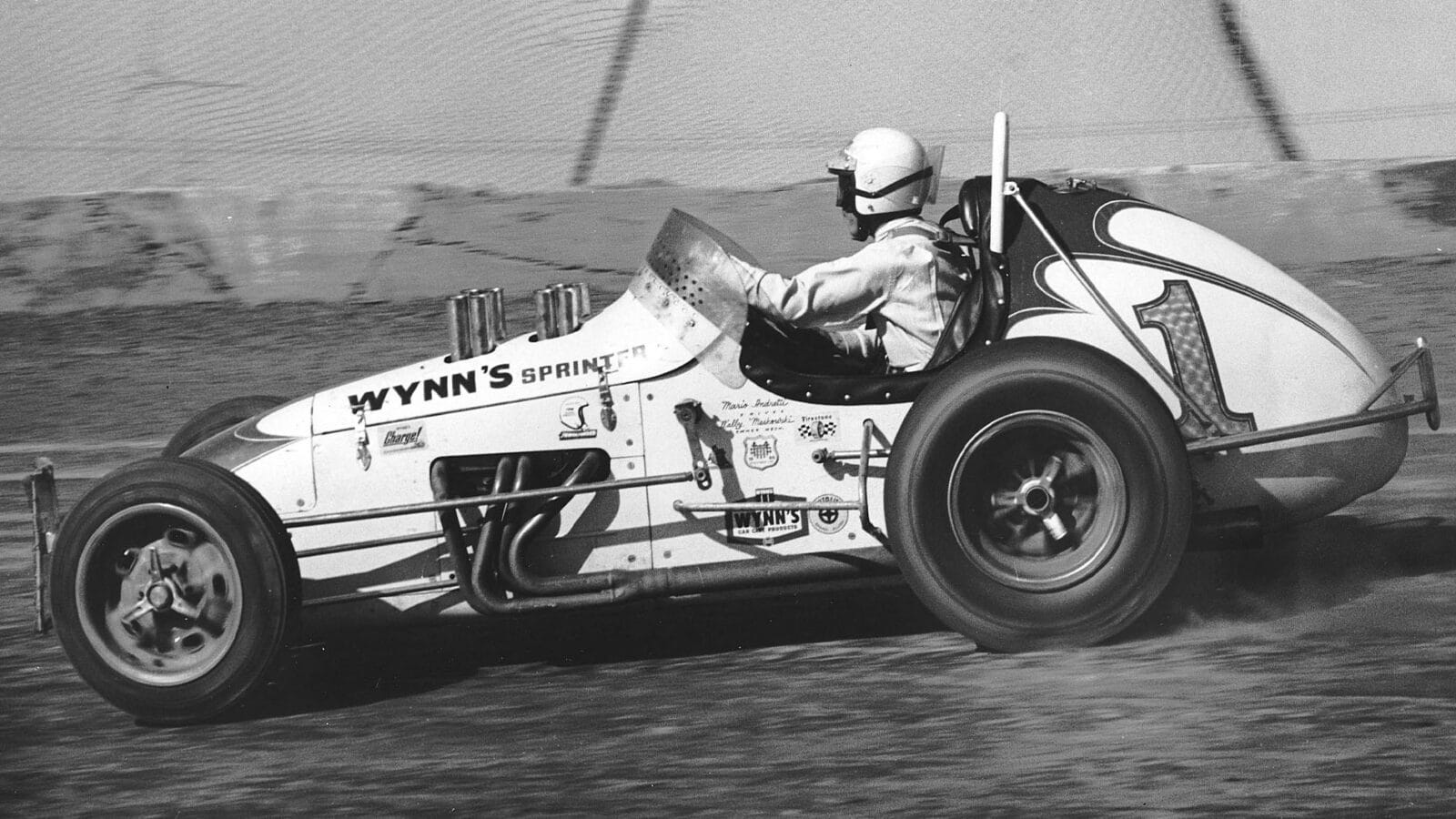

Never say never again, but it is reasonably certain that Andretti will be the only driver in history to graduate to F1 from the bullrings of grassroots US racing. On June 21 1964, while Jackie Stewart will have been racing Ken Tyrrell’s F3 Cooper-BMC somewhere, Mario was at the wheel of the Windmill Truckers Special at Langhorne, the most feared race track in America.

“Langhorne,” says Andretti firmly, “was the only track I ever felt intimidated by – that was the only race in my whole life where, the night before, I really was very concerned. Never happened any other time – not going to the Nürburgring for the first time, not anything. I had never, ever driven a champ dirt car, and now I was going to – at Langhorne, of all places. I said to myself, ‘I’m on my way to Auschwitz…’ That was how people felt about that place.

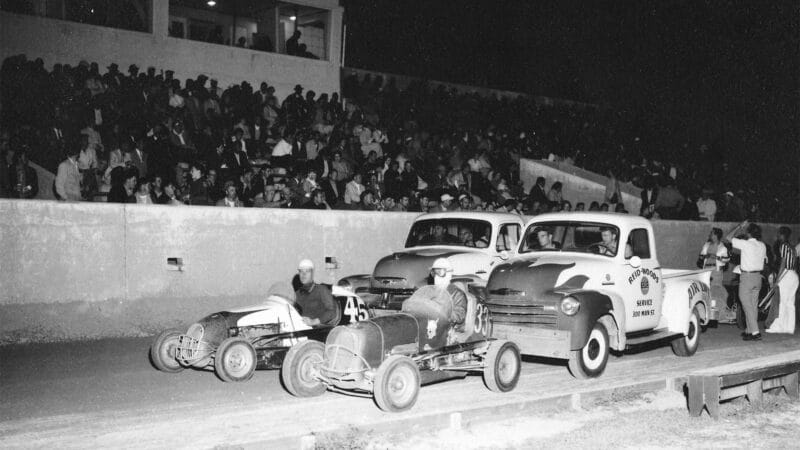

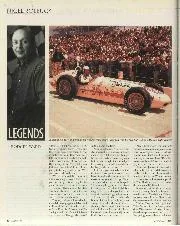

A crash in 1950 Cemar Bowl, Cedar Rapids, Iowa – no one was hurt, miraculously

Getty Images

“One of the greatest drivers of that period was Rodger Ward – he won the Indy 500 twice, and he was also a fantastic driver on dirt. But Rodger flat refused to drive Langhorne. Trust me, it was like nowhere else. Even now, when I think about it, I get goosebumps…”

The town of Langhorne is situated about 15 miles to the north of Philadelphia, in Pennsylvania’s Bucks County, but no trace of the speedway remains. The last race was run there in October 1971, after which the place was razed to make way for – yes – one more faceless shopping centre.