At the front there was a simple, unequal length, double wishbone arrangement while, behind, a lower wishbone layout used the driveshafts in place of the upper links. Look at the suspension of an XJ6 and you’ll find a not dissimilar arrangement. Coil springs replaced the torsion bars found on previous Jaguar racers and adjustable anti-roll bars were fitted at either end.

It is a shame that we were never able to see how such a formula would have fared in competition but, by the time the wheels of development had slowly run their course, it had been left behind, its 2478lb kerbweight leaving it hopelessly overweight. All we know for certain was that, in 1967, David Hobbs drove it around the MIRA Proving Ground near Nuneaton at an average speed of 161.6mph, claiming the then-fastest lap of a UK circuit.

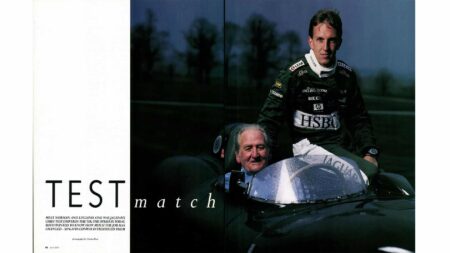

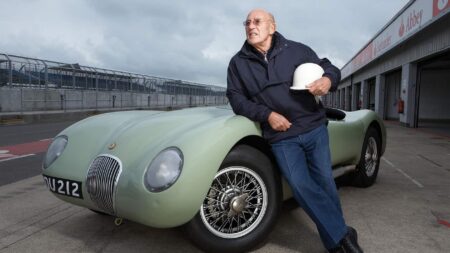

We’re back at MIRA today, the track with which the XJ13 was associated at first and then, some years later, upon which it would become indelibly imprinted. Yet it isn’t Hobbs at the wheel but an unfeasibly sprightly septuagenarian with a flat cap and cheeky grin. This is Norman Dewis, 73, Jaguar’s chief engineer from 1952 until 1985 and the man who, one day in 1971, had his life saved by this car.

XJ13 was designed exclusively to win Le Manse, hence its long tail for maximum Mulsanne speed

David Burgess

“It’s a day I’m not likely to forget It happened on January 20 at 3.50pm. The XJ13 had been in mothballs for some years after the project was cancelled but they decided to dig it out when we put the V12 into the road cars. We were only at MIRA to do some promotional filming, not for any serious running. I’d been driving around the banking slowly for most of the afternoon but the director said he wanted a few quick laps. I did two pretty close to flat-out and decided to do just one more before calling it a day. Coming off one of the banked turns, the off-side rear wheel, which takes all the load, just collapsed. I was doing about 145mph.

“The car started to leap up the banking but I managed to pull it away from the edge. Then I switched off the engine and, once it was clear that there was no more I could do and that there was about to be a fairly massive accident, I wriggled down under the scuttle and hoped for the best.”

“Sir William Lyons wanted nothing more to do with the car and the wreck sat under cover in a corner of the workshop until 1975”

The perhaps unwisely named XJ13 dug itself briefly into the soft earth on the infield and then flipped. Dewis remembers it went end over end twice before starting to barrel-roll. Three complete revolutions later it finally came to rest, a bruised but otherwise unharmed Dewis still firmly wedged under the dashboard.

“I just walked away from it. After that Sir William Lyons wanted nothing more to do with the car and the wreck sat under cover in a corner of the workshop until 1975, when the rebuild finally took place.”

A remarkable amount of the original car was saved. Despite the fact that the front and back of it were now missing, the vital central box section had withstood the impact well while the engine and gearbox remained intact. Once back to its original glories, the XJ13 was sent out as an ambassador for the marque, visiting the US and Australia and finding a permanent home in Jaguar’s Browns Lane museum. It has been back to Le Mans and, last year after a lengthy engine and suspension rebuild, was seen charging up Lord March‘s front drive during the Goodwood Festival of Speed.