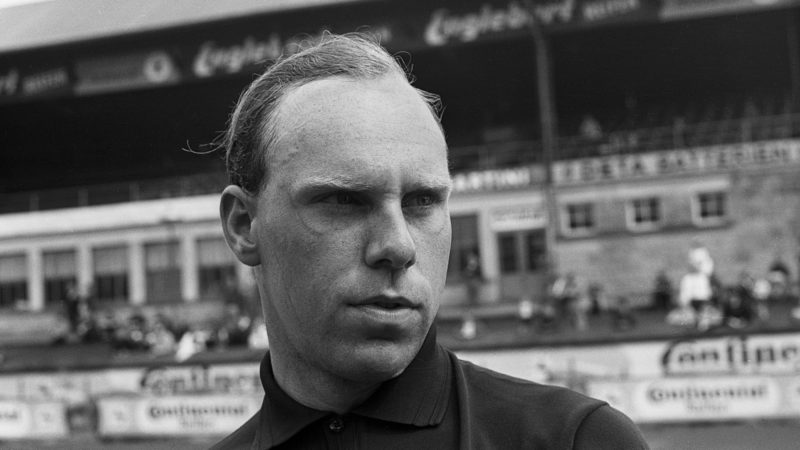

“My drive there in ’68… it was a good drive, I think, but! felt, on other days, I’d driven better races and got no reward. At Monaco I didn’t know how to pace myself because, apart from a one-off for Cooper at Mosport the year before, I hadn’t driven a grand prix car since ’65. “The thing is, we didn’t have fitness people to keep us going back then — it was just down to you. You were very much on your own. If I’d known a bit more about it, I might have gone harder at about two-thirds distance, but every time I speeded up, Graham did the same. He definitely backed off towards the end, but I’ve no idea how it might have gone if I’d speeded up a bit earlier.”

Pretty unassuming, you would have to say. Attwood never outqualified Rodriguez again, scored no more points that season, and was dropped by BRM before the end of it, but that day at Monaco he looked superb, a man wholly in his element.

A year later he was back there again, this time as team-mate to Hill in a works Lotus 49, standing in for Rindt, who’d been hurt at Barcelona. The results were less spectacular this time — 10th on the grid, fourth in the race — but it was a tidy drive, and it scored some extra points for Lotus. Colin Chapman was well pleased.

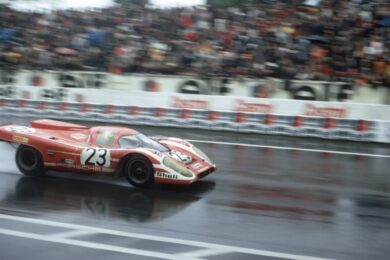

Attwood and Herrmann confer during their Le Mans-winning drive of 1970

Porsche

It is as a sportscar driver, though, that Attwood’s name is best remembered, and particularly with Le Mans, and the fabled Porsche 917.

Anyone who ever raced a 917 reacts the same way when you ask how it was to drive. In 1969, the year of its debut, drivers detested it, for while it was shatteringly fast, so also its cockpit was deafening, its on-track manners wayward. Richard thought the original, long-tail, car nightmarish.

“It was purely aerodynamics, and once they’d been sorted out, the most frightening car I ever drove became about the best. It was simply a matter of going to a short, swept-up tail, and then the car worked fine. Porsche never thought the problem was with the aerodynamics, but those were the days of hit-and-miss engineering — even today aerodynamics is a bit of a black art, I think, at Mulsanne speeds.

“The early cars had the exhausts coming under the doors, and after the first stint at Le Mans in ’69, I was completely deaf and I had a blinding headache. It was a hugely uncomfortable car to drive — and the bloody thing lasted for 21 hours! I hadn’t won Le Mans at that stage, but still I was quite happy to get out of that car.”