Lotus fragility and mystery monster revealed Letters, July 2021

Sir Jackie Stewart’s view that a “too fragile” Lotus stymied Jim Clark’s success at Monaco [Monaco masters, May] deserves further scrutiny, particularly given that Chapman’s cars won five Monte Carlo races between 1960 and 1970. Few would disagree with Stewart’s premise that ‘Chunky’ Chapman’s approach to car design often compromised his machinery’s resilience, but Jimmy’s failure ever to win a Monaco Grand Prix deserves some context. Clark started four of his six Monaco Grands Prix between 1961 and ’67 from pole (he missed the ’65 race due to a clash with Indianapolis). He suffered four retirements, two of which can be directly attributed to Lotus design fragility (suspension failures in 1966 and ’67). Gear and engine troubles halted his Lotus 25 in 1962 and ’63.

Although Clark reached the finish of his first Monaco Grand Prix in 1961, a stop to rectify an ignition lead fault destroyed his race. His 1964 event was marred by a scrutineer-enforced pitstop to address trailing parts after swiping a marker – but Clark still finished fourth.

Lotus fragility certainly played a part, but so did bad luck. And tragically we never saw Jimmy in a Lotus 49 there –a machine that was to be victorious in every Monaco Grand Prix it started.

Max Kingsley-Jones, Iver, Bucks

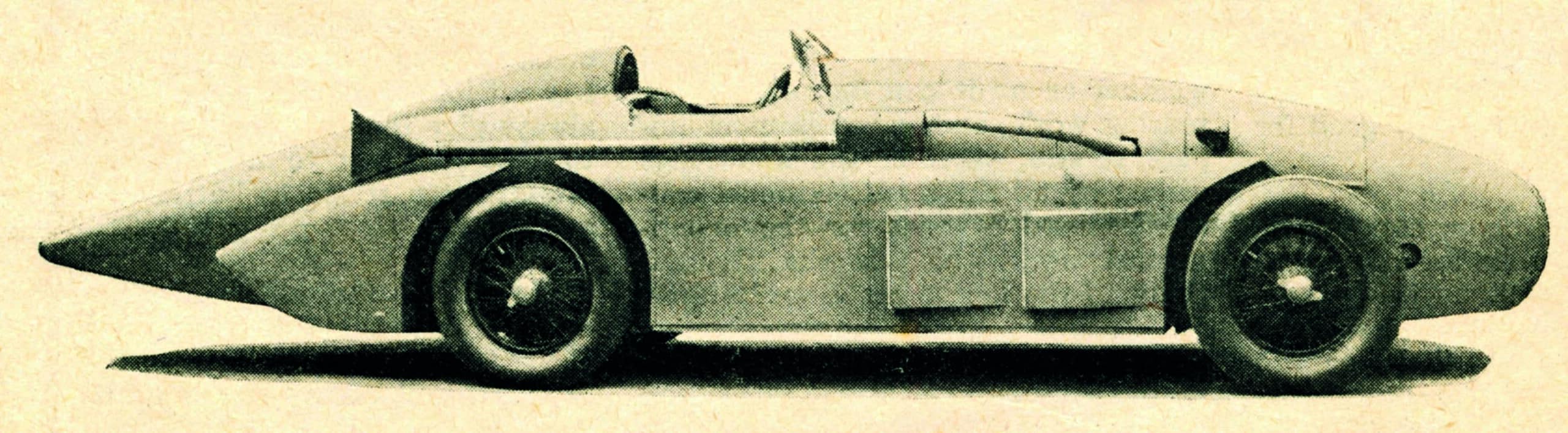

I was amazed to see in the June issue [Letters] a photograph of the streamlined car I had been looking at that very morning in The Autocar. With the WO Bentley Memorial Foundation, I am involved with a biography of Frank Clement, the racing driver and engineer who worked and raced for Bentley Motors in the 1920s. This morning I was looking through Frank’s archived cuttings from the newspapers and motoring journals of the day including SCH ‘Sammy’ Davis’s column for The Autocar under the pseudonym Casque.

In The Autocar of July 11, 1930, the above photograph was captioned, “Built with side radiators resembling those of the Golden Arrow, this machine, a six-cylinder Graham-Paige, is to race at Brooklands.”

Sammy describes the car as built “with a great deal of trouble and ingenuity” by John Pillin who ran a garage at Beckenham, for Mr G Pauling. Pauling is mentioned in Bill Boddy’s Brooklands work as an entrant of a supercharged Graham-Paige in the BARC Closing meeting of 1930, but there is no mention of car or driver in the Motor Sport report. By 1931 he was driving a Riley and had possibly moved the Graham-Paige on. However, as suggested by Iain Nicholson, he had registered it for the road. After this I do not know what happened to this car. What a pity the Edinburgh photograph is undated.

Sammy Davis notes that the 4.7-litre sixcylinder Graham-Paige chassis had had to be “practically reconstructed from end to end”. A Reval supercharger fed the side-valve engine. The radiators were in pontoons on either side, with a neater appearance than your – presumably later – photo showing a huge rectangular opening, perhaps due to overheating problems. The original dynamo lighting system and starter had been retained.

I hope that others are able to solve the mystery of what the future held for this amazing-looking machine.

Will Morrison, by email

The Jacky Ickx interview [May] brings back my fondest motor sport memory. In 1968 at the young age of 13, I was fortunate to attend the 6 Hours at Watkins Glen where the No6 Ford GT40 driven by Hobbs/ Hawkins had a substantial lead of maybe 40 seconds over the No5 GT40 of Ickx/Bianchi with approximately one hour to go in the race. Here I was sitting on top of my friend’s father’s 1960 Ford Falcon station wagon, stopwatch in hand timing the gap between the two cars. As Ickx kept closing the gap it brought me to my feet in nerve-racking anticipation. Then it happened. Here came No5 driven by Ickx with his headlights on ahead of No6. He would go on to win, and a new racing fan was born. To me Jacky Ickx driving that beautiful Ford GT40 dressed in the Gulf colours of light blue and orange to victory was something that will be etched in my brain forever. You were the best, Jacky.

Tom Perry, Rochester, NY, USA

With regard to Mark Hughes’ (always interesting) regular feature in the June issue, I was reminded of a quotation by Sir Sydney Camm, designer of, among others, the wonderful Hawker Hurricane: “All modern aircraft have four dimensions: span, length, height and politics.”

I do feel there to be a valid analogy with modern F1…

Chris Mabon, Lechlade, Glos

In his editorial in the June issue, Joe Dunn reflects on the participation of women in modern motor sport. But it isn’t necessary to look at the rarefied world of the Indy 500, let alone the W Series or the bizarrely contrived Extreme E for examples of diversity, not when there’s ample evidence so much closer to home. In the research for my recent book (Driven, an elegy to cars, roads and motor sport) I attended as many different UK motor sport events as possible over a 12-month period and two genres stood out as being almost completely gender-blind. Drag racing has a rich history of female participation, from Shirley Muldowney in the 1970s to Anita Makela and Jndia Erbacher in the present day. As for Autograss, it is not unusual to see up to three generations of the same family competing in this spectacular, accessible but under-reported series. Mainstream motor sport could learn a great deal from either genre, because they offer spectacle and diversity often lacking elsewhere.

John Aston, Thirsk

Simon Arron’s Fully Charged article [May] about Extreme E at least didn’t make the same claim as was made in a BBC News report, which claimed it to be, “… the first gender-equal” form of motor sport. Of course, nothing could be farther from the truth, as all forms of motor sport are genderequal. There is no gender differentiation as there is in tennis, football, and most other sports. The only differentiator is the stopwatch. (Or when you stop the startwatch as a much-missed commentator once said.) It could be said that Extreme E is the first non gender-equal form of motor sport, being based on the artificial construct of a male and female competitor in each crew.

Ian McRae, North Lanarkshire

I was delighted to read Derek Hill’s article about his father and the reborn Sharknose Ferrari he drove at Reims in 2019 [Lost Ferrari rides again, June]. I was there and had the great pleasure of a chat with Derek, as well as talking with one of the mechanics who took part in the recreation of these magnificent cars, one featuring a 65-degree and the other a 120-degree V6. The story of their recreation is told by Jason Stuart Wright in the remarkable Sharknose V6 by Jörg-Thomas Födisch and Rainer Rossbach.

It could almost be 1961 again. Reborn Sharknose Ferrari about to re-enact Phil Hill’s Reims debut

Reims brought Phil Hill’s first start in an F1 grand prix and Fangio’s last, in 1958. The pits and further historical buildings along the narrow straight between Thillois hairpin and the right-hander shortly before Gueux have been restored by a group of dedicated fans with more enthusiasm and skill than money, Les Amis du Circuit de Gueux.

Their meeting of September 2019 was a big popular success starring both Ferraris and Jim Clark’s original Lotus 21. The kids were enthralled at the sight and noise of the old race cars, as I was myself in period, merely watching them on TV and photos: the dream lives on. After two years of Covid break, the next event will take place in September 2022. Meanwhile, we’ll be looking forward to the release of Derek’s film. I can’t wait!

Jean-Marc Creuset, Gueux, France

Ferrari designer Carlo Chiti captured in the Monza paddock in characteristic pose, and dress, by reader Michael Cookson

Your Parting Shot picture of Carlo Chiti in the June edition is very similar to a picture I took (above) some 22 years earlier in the paddock at Monza during the 1960 Italian Grand Prix.

Carlo – still wearing a tie – is sitting outside the garage housing Phil Hill’s winning Ferrari, possibly contemplating the Sharknose Ferrari 156 which he designed and which was to appear in 1961. The 1960 Italian GP, which had been boycotted by the British teams over the use of the banking, was the last to be won by a front-engined car.

I happened to be at Aintree for the 1961 British Grand Prix where Wolfgang von Trips won in the Sharknose Ferrari. This grand prix was the first time a four-wheel-drive car entered a GP, the Ferguson-Climax driven by Jack Fairman, and I believe it was the last GP in which a front-engined car was entered.

Michael Cookson, Audlem, Crewe

The issue of track limits is spoiling the show. There is little consistency in how they are applied, and frequently no slow-motion replay to show the TV audience the degree to which the limit has been exceeded. Once live attendance is returned to normal, there is no way the trackside crowd can see the transgression.

On street circuits there is no issue. You leave the road, you hit the barrier, and your race is over. Back in the day, straw bales, trees or actual kerbs formed the natural track limit. Exceed the limit, and suffer the consequences.

Wouldn’t it be simple to say, the ‘black stuff’ is the track, anything else is not. The cars are fitted with GPS devices and the width of the car is known. An electronic device could simply be triggered to reduce engine power by x% for say 10 seconds should the car not stay on the black stuff. That would be sufficient motivation to the drivers to keep the car on the track, while not spoiling the show.

Robert Hindle, Mississauga, Canada

I was pleased to read in the June issue [Matters of Moment] that MSV has agreed to purchase Donington Hall and the surrounding estate. Its commercial plans for the property seem sympathetic to the circuit. However, questions still remain over the future of the Donington Collection, which closed in the autumn of 2018.

At the time, Jonathan Palmer said that he was committed to preserving the racing heritage of Donington, but that MSV had decided not to continue funding the museum as it felt that a “general interest” display (referring to the latter-day amalgam of racing cars and military vehicles) in such old buildings was not the best way to achieve this.

Surely there is a place for a large museum to celebrate Britain’s motor racing heritage and the importance of motor sport to the British economy? Although a number of the collection’s star exhibits had to be sold off, the bulk of the car collection remains intact, though Kevin Wheatcroft has been quoted as saying that it would cost in the region of £4m to build a modern museum to house both the racing cars and military vehicles.

It is fair to say that Kevin’s first love has always been his military vehicle collection, but though he has also stated his commitment to preserve the car collection, could he be persuaded to sell it as a whole, if a buyer with suitably deep pockets could be found who could offer firm guarantees about its future?

Bernie Ecclestone, a man to whom motor racing has been good, springs to mind, as he has a superb racing car collection of his own, which apart from the odd demonstration run and display, is, sadly, not on public view.

The two collections combined would provide a truly world-class visitor attraction, and as even Bernie must concede that he won’t live forever, then maybe it’s time to put something back?

Nick Procter, London, SE12

Contact us

Write to Motor Sport, 18-20 Rosemont Road, London, NW3 6NE or e-mail, [email protected]