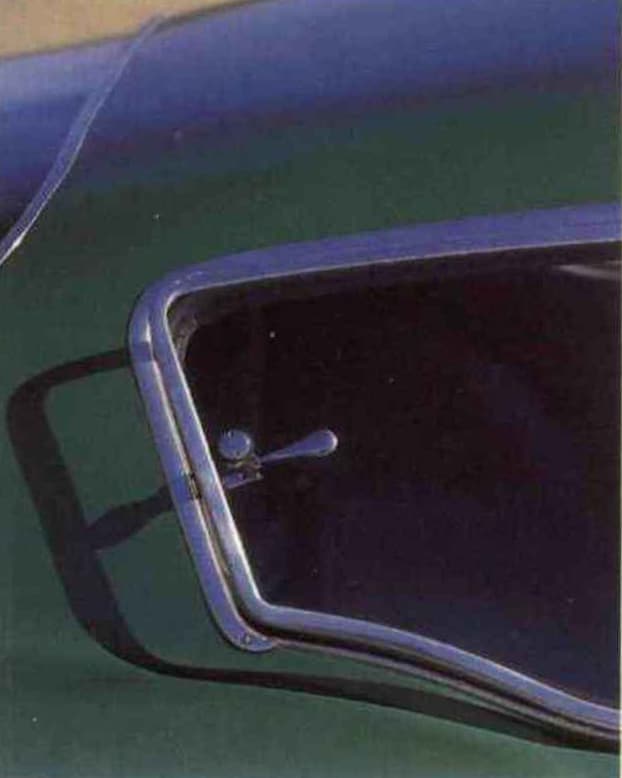

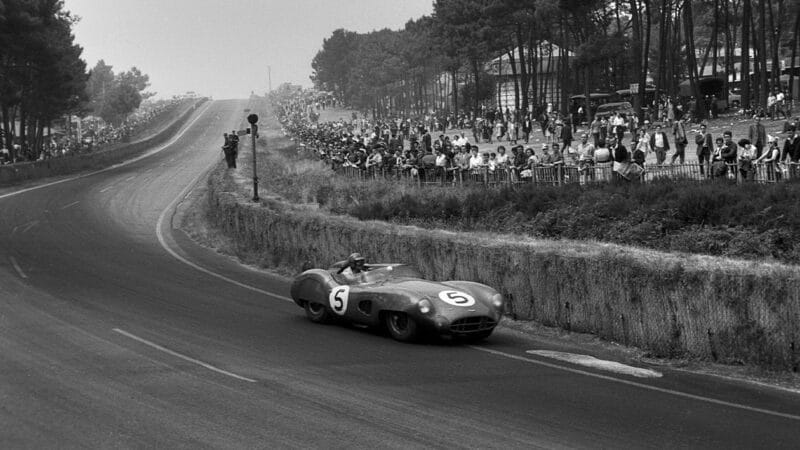

The Zagato was always going to be first out on to the track. Photographs of Jim Clark slithering around Goodwood in this car have lived in my head for as long as I have had memory and, now that it was mine for a while, I lacked the power to delay our meeting any longer. Besides, with its beautifully presented and trimmed cabin, map holders and ashtray, it seemed an entirely easier way to introduce myself to racing Astons than to attempt either of the starkly brutal open racers.

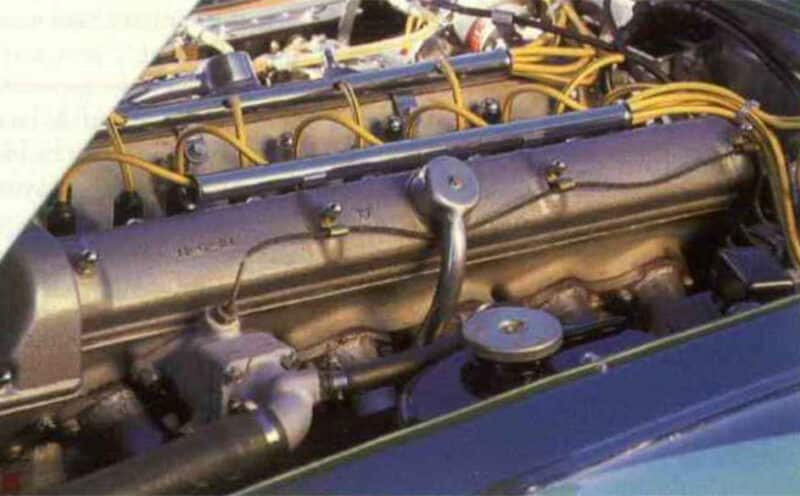

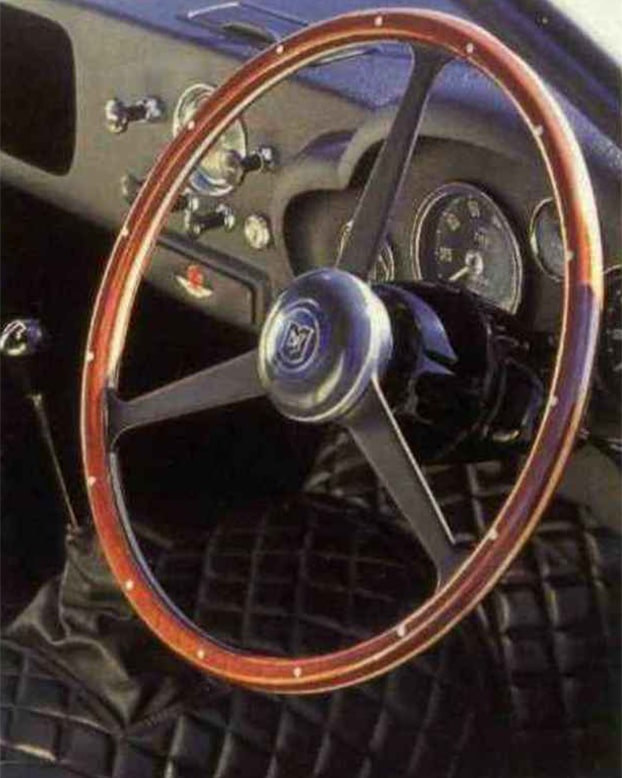

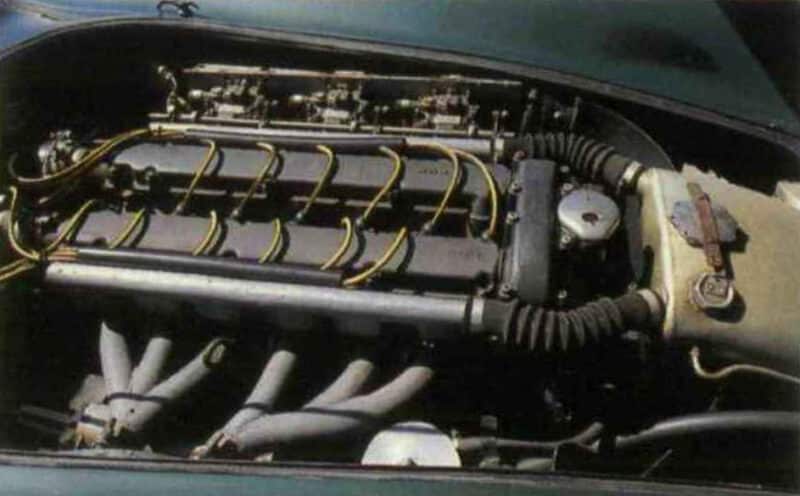

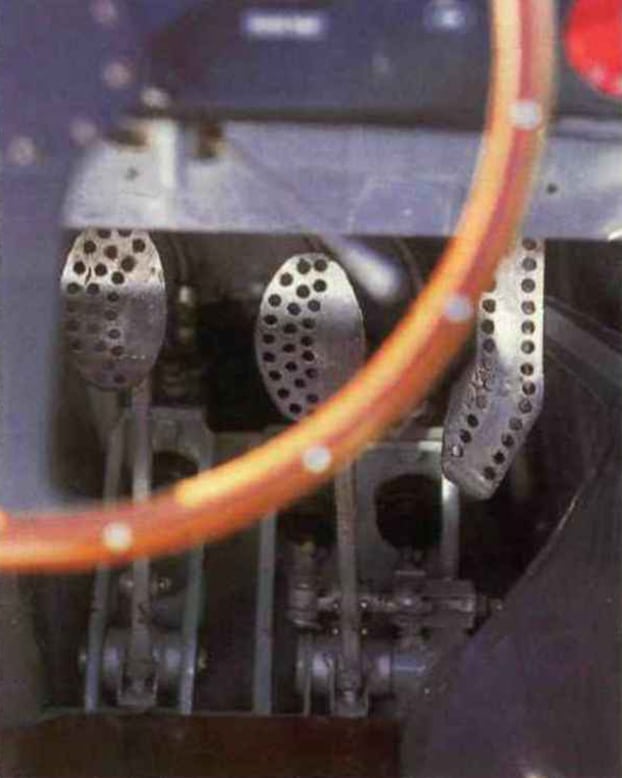

I wonder whether you will be pleased or disappointed to know that 2 VEV is a remarkably easy car to drive. Anyone with a brain and a driving licence could climb aboard, twist the key, select a gear and rumble off into the sunset. I was surprised. The clutch is heavy and a little sharp, but so laden with torque is its gorgeous 3.7-litre, twin-cam, 12-plug engine that getting going is never a problem.

The driving experience is dominated by that engine. Despite tin-foil-thin 18-gauge aluminium bodywork that dents as you touch it, the Zagato never feels like a particularly lithe, light car, yet with that motor pouring on the power in one solid shove from 2000 to 6000rpm, it still feels mighty quick. So broad is this band that, in fact, its four widely spaced gear ratios cope admirably, the lever swapping between them with that particular breed of well-oiled precision that is uniquely and unmistakeably Aston Martin.

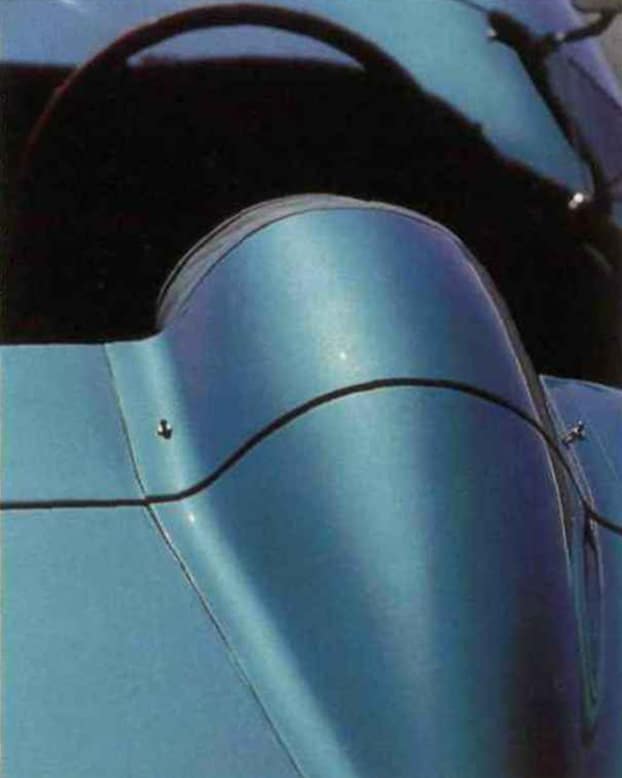

Current set-up of 2 VEV inhibits Clark-style four-wheel drifts but one-wheel lifts are possible

It is, however, not the car I’d imagined. What I thought would prove a pure racer with only a visual doffing of the cap to the niceties of road cars turns out to be a truly sophisticated GT car that would prove as at home barrelling down to the South of France on a sunny day as negotiating the tight turns of the Stowe circuit.

Willie concurs: “The Zagato really is a bit of a compromise as a racing car, being, as it was, a road car which was converted for use on the track. The factory, in fact, was very successful but there were problems. The chassis was never as good as that of a Ferrari 250GTO. The engines were probably a bit more powerful and they certainly had more torque.

“Even so, it’s helped by its Dunlop racing tyres for track work. This car’s been set up with a considerable amount of suspension offset that it would not have had when new and it has rather more grip at the back, making it push into understeer. I’d like to try it with the same size tyres on at each end, too. I remember those shots of it when it was racing in perfect four-wheel drifts. You couldn’t do that in this car as it is.”

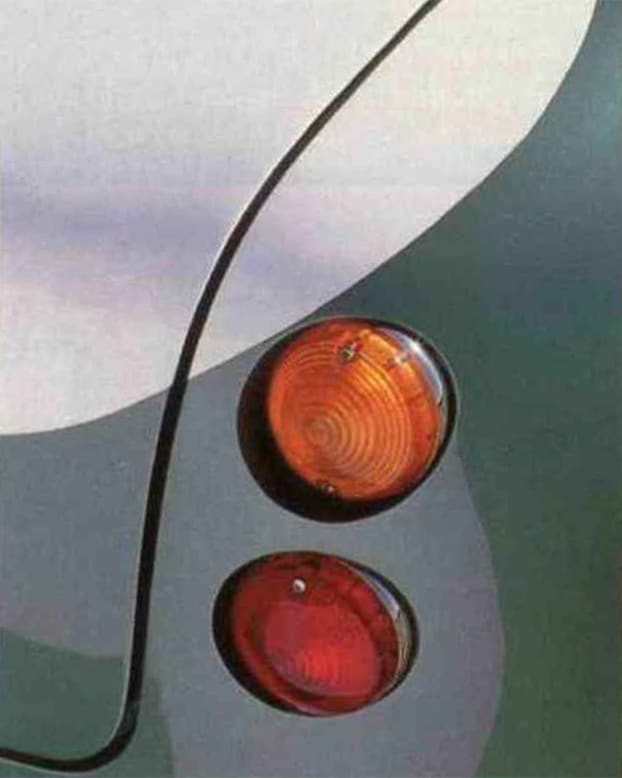

And so it is. Hurtle up to a corner in the Zagato, note its fine brakes and, as you turn the wheel, you can feel the nose fighting shy of the apex. It can be driven around easily enough with a quick lift followed by a bootful of throttle, a technique which will bring the nose straight back into line, lift a front wheel and kick the tail out. Yet rather than being a natural state, it is one which is to be striven for. It seems scarcely credible that the Zagato and DB3S competed at Le Mans 24-hour races separated by a mere three years. The explanation is that while the sportscar was right at the end of its natural life, the GT was just setting out. Conceptually, there is the thick end of a decade between them. As a car to pore over, 62 EMU is the most fascinating of the lot. Though the DBR1 is authentic, it is also an actively campaigned racer, immaculately prepared and maintained in perfect condition; the Zagato has retired from racing now and sparkles, fresh from a total rebuild after an appalling road accident in 1993.