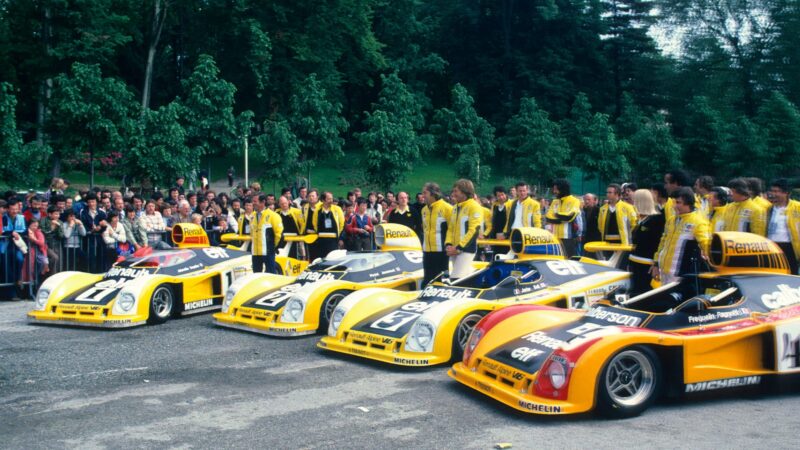

The team, too, was better prepared than ever before. The amalgamation of Alpine, Gordini and Renault into Renault Sport during 1976 was slowly eroding the rivalries within this Unholy Trinity: less liberté, but more egalité and fratemité. The man behind this unification was Larrousse. He had driven for Alpine at Le Mans in 1967-68 — and been unimpressed. His later, successful spells with Porsche and Matra had been much more to his liking, and he wanted to instil this same cohesion at Renault. He was indubitably thorough, but this process was not the work of a moment — as 1976 had proved.

Larrousse’s first race in charge, for instance, should have been a walkover at the Nürburgring. Instead Jean-Pierre Jabouille and Patrick Depailler, under strict instructions not to race each other, slid off on the first lap. France had a wealth of speedy talent, but appeared to be short on team players.

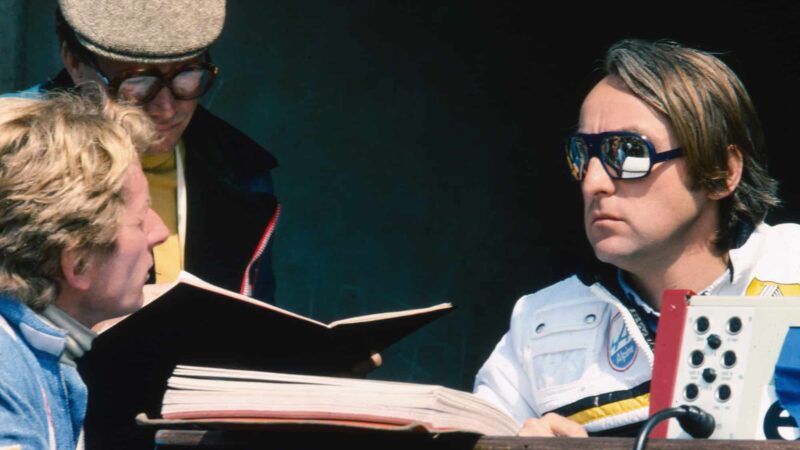

Forty-year-old Jean-Pierre Jaussaud knew that this was his calling card. A late starter in the sport, he’d been French F3 champion in 1970 with Tecno and the runner-up in the ’72 European F2 series at the wheel of a Brabham. The following year he finished third at Le Mans for Matra, a result he repeated in ’75 with Mirage. As the ‘Elf’ generation flourished, this moustachioed man from Caen knew he was not the apple of single-seater team managers’ eyes, and that the long-distance stuff would be his future métier. Renault Sport’s young guns had other strings to their bows, F1 and F2, and so he knew that Larrousse would need a workhorse to bear the brunt of the A442 programme…

“For a long time I was on the telephone to Larrousse persuading him to let me test the car. I knew that he had no real need of me for the race, and that this was the only possibility of me getting a drive,” says Jaussaud cheerfully. Larrousse eventually gave way. “I enjoyed all of the testing, working with the designers and engineers. It was an important job and I was happy to do it.” He was even happier when he was rewarded with a place next to Patrick Tambay for the race. Sadly, their A442 would register the first of the three stunning retirements.

Alpine A442s couldn’t hold on to their lead in 1977

DPPI

After four hours the squad held a comfortable 1-2-3; the nearest works Porsche was in 15th place. However, one by one, they were sidelined by the same problem: a melted piston. ‘The Muldoon’ had got ’em. Nothing, it seemed, could prepare you for it.

One month later at Silverstone, Renault made F1 history with the first appearance of its turbocharged RS01. It should have done so on a wave of euphoria: Le Mans a feel-good memory, F1 its exciting future. Instead it knew that it would have to return to La Sarthe, for Le Mans had to be won before F1 could become its priority.

All of this would’ve been dismissed as ridiculous just five years before: Renault was a motorsport minnow, as François Guiter, the go-ahead competitions boss of Elf, was about to find out. He had a problem: Matra’s Simca deal meant that Elf would have no front-line representation at Le Mans in 1972, for Simca was tied to Shell. In response he approached Renault.

Cowed by the ‘dreams of victory’ and subsequent failure of the Alpine V8s at Le Mans in 1968, Renault had washed its hands of motorsport. Thereafter it appeared content to bask in the reflected glow of Alpine’s numerous rally wins – and pretend that Matra’s racing successes weren’t happening. When Guiter proposed that it should build a racing engine for the European series for 2-litre sportscars, as a stepping-stone towards a fully-fledged Le Mans assault, he was met by careworn inertia. Undaunted, he simply handed the budget to a new generation of engineers at Gordini’s Viry-Châtillon factory and told them to get on with it. They did.

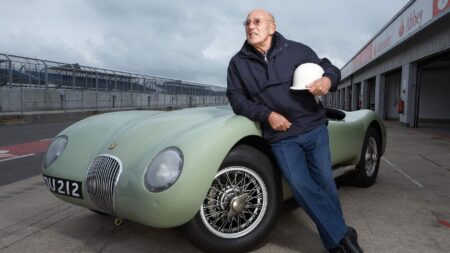

Early victory raised expectations too high, too soon

Designed by Castaing and Boudy, the 90-degree V6 CH1 produced an encouraging 270bhp and was soon dropped into the tail of Alpine’s new 1973 sportscar. Conceived by André de Cortanze, the A440 was a neat, simple, multi-tubular machine that suffered from understeer and a lack of torque and reliability. The longer, narrower A441 of 1974 was much better. With 285bhp driving through a stronger Hewland (FG400) ‘box, this 575kg machine dominated the 2-litre series, scoring a championship 1-2-3 with Alain Serpaggi, Jabouille and Larrousse. It was time to step up.

That Alpine-Renault was able to do so was thanks to the foresight of colourful team boss Jean Terramorsi, and the youthful vigour of Dudot. The latter’s colleagues had thought him mad when he bolted a Garrett turbo onto one of Renault’s R16 four-pots. Even when they saw the figures this generated they still expressed doubts. In truth, these staggering numbers came hand in hand with a precipitous power curve and hideous lag – yet Jean-Luc Thérier somehow conjured a victory in the 1972 Critérium des Cévennes out of his all-or-nothing A110 Turbo. Terramorsi was convinced and sent Dudot to the US to learn more about turbos. Renault’s recurring bhp problem was about to come to a dramatic end.