“After that I won a couple of handicap races at Goodwood and then sold the car. I thought my racing days were over but then John Wyer – who had been the MD at Monaco Motors and was now Aston Martin’s team manager – phoned me at the office and asked if I’d like to test a DB2 at Silverstone. Charles Brackenbury, who was a wonderful old soak, went out to give us an idea of what a correct lap time should be. Jack Fairman was there, too, as was John Gordon who later made the Gordon-Keeble motor car.

“John Wyer had a gift for pairing professional drivers with amateurs like myself. As long as you behaved, he was all right. If you didn’t, you got the treatment. If you made a mistake, though, he was incredibly generous in not blaming you; he would give you the benefit of the doubt. I was offered a drive at Le Mans for 1950 and was paired with Jack. Unfortunately, he went off the road on the way to the circuit, damaging the car and breaking his wife’s neck. John Wyer considered him unfit to race so I was teamed with Gordon in a development hack known as the ‘Sweat Box’. It lasted only eight or so laps before the crank broke. That was my first race as a works driver.”

While his day job as a marine insurance broker paid well, one thing Thompson lacked was time. “We used to get two weeks holiday a year and every other Saturday off. I had a living to make and had to plan my racing around work, although every once in a while there would be a funeral that I absolutely had to attend… Wyer said it was no good me turning up for one or two races each year and I’d better get in some practice. Tom Ayrton kindly loaned me a Bugatti Type 51 and I rather foolishly bought a Cooper-Vincent, which was very fast in practice but always broke down in a race. It wasn’t quite the experience I was after.”

Though more than useful in sprint races, Thompson’s metier was clearly endurance events: 1951 would witness arguably his finest achievement. “That year I was paired with Lance Macklin in the works DB2. He was very much the coming man and a very, very good driver, as long as he could be bothered. We drove in four-hour stints and while I was in the car he’d disappear off to see some bird. We were lying about fifth or sixth at half-distance and had stuck religiously to the imposed rev limit. Wyer then gave us another 300rpm to play with and for the last 12 hours we drove flat out. I remember Brian Shawe-Taylor in the lightweight Aston, and just slowly, slowly gaining on him. When he went through White House he would lift off or brake ever so slightly. I knew that if I could go flat through there I would have a few more revs and could pass him on the straight. The chase was wonderful and we were stationary for only 11 minutes during the whole race. Lance and I finished third overall and won our class. To do so well with a road car up against 4.5-litre Talbot-Lagos and the Jaguars and so on was, well, pretty special.”

Parnell/Thompson DB3 runs behind a Frazer Nash Le Mans-replica en route to victory at Goodwood in ’53

GP Library via Getty Images

The following year’s running, by comparison, was less successful. With the arrival of former Auto Union man Eberan von Eberhost, Aston Martin had upped the stakes. As chief engineer, he conceived the slab-sided DB3 in time for the ’52 Le Mans race. “There were three cars, the one I shared with Reg Parnell being an experimental coupé; it was too heavy to be competitive and we were out before long. The DB3S was much better – well balanced, very forgiving – but none of us finished in 1953.

And in the following year’s race I was given the 4.5-litre Lagonda, which I suspect none of the professionals on the Aston team wanted to drive. That was the year when all the works cars went out in accidents, two of them at White House. They were insured by Lloyds and I remember getting slow handclapped when I walked into the office on the Monday after the race!”

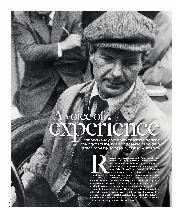

It was aboard a DB3S that Thompson enjoyed one of his higher-profile wins, in the ’53 Goodwood Nine Hours, a full 12 months after a fire at the same venue almost claimed him. “In ’52 I’d been driving the DB3 with Reg (pictured on p92). There was a trail of smoke coming out the back which wasn’t affecting the performance but, when I came in to hand over, instead of Reg jumping in he took my arm and pulled me away as the car went up in flames. There’d been some confusion over strategy and the car was overfilled with fuel – a red-hot brake caliper sent it up with a whoosh and John Wyer got badly burned, as did a mechanic. In ’53, we were running near the front for much of the race and on the last handover Reg informed me that it had no clutch; I drove away on the starter motor. All the Jags fell by the wayside and we won. We were lucky.