Page 3

Editorial, March 2000

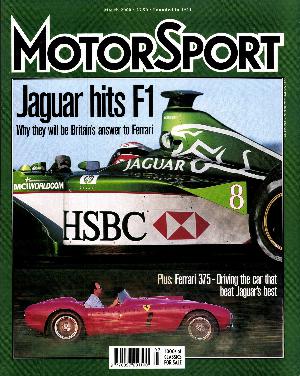

There seems to be considerable debate surrounding how much Jaguar should lean on its heritage during its foray into Formula…

There seems to be considerable debate surrounding how much Jaguar should lean on its heritage during its foray into Formula…

THe return of the prodigal son, Nigel Mansell, to July's Coys International Historic Festival will add thousands to the gate…

Motor racing paintings and prints by father and son Michael and Graham Turner go on show in London in February.…

The 38th Daytona 24-hour race has been won outright by the ORECA Chrysler Viper of Olivier Beretta, Karl Wendlinger and…

Motorsport's World Governing body, the FIA, has given its approval to the renamed European Sports Prototype Trophy series which will…

The motor sport's association (the governing body of motor sport in Great Britain) has recognised the huge popularity of historic…

Ford Falcons, Mustangs and Galaxies will head a horde of pre-'65 Historic Touring Cars in the Top Hat Challenge, three…

Those of us who haven't rebuilt the engines of our classic cars to run on unleaded may have a lifeline.…

The non-availability of brands Hatch's Grand Prix circuit for the Historic Sports Car Club's Historic Superprix on July 1-2 has…

The first Lola Grand Prix car will be back on track this season, after 31 years in the Donington collection.…

Mike Cotton interviews new FISA president Max Mosley Ilooked in my shaving mirror this morning and thought, 'Gosh, at long…

Time was when an ambitious young driver could slide into F1 almost unnoticed, develop his skills quietly and rise towards…

Sir, I thought there was something familiar in the Alan Smith study of a so-called Le Mans Replica Frazer-Nash at…

Sir, Thought I'd send this "Artist's Impression" of Gordon Murray's Formula One 2000. I AM, YOURS, ETC Bruce Thomson, Unionville,…

Sir, Being a fan, I was delighted to see two pictures of my car in your January 2000 issue (Carrera-PanAmericana…

Sir, Concerning two captions in your Nurburgring Track Test. 1. The Karussell: "...the only boring corner on the track." Only…

Sir, I read with interest the article entitled 'Fiberglas'. I have a long term interest in this material and Keith…

Sir, With reference to Geoff Whyler's letter concerning the May 1958 Silverstone race between Archie Scott Brown and Masten Gregory,…

Sir, Thank you for the review of Michael Oliver's Lotus 49 book. Unfortunately, it attributes the book to Virgin instead…

Sir, With reference to WB's page from the January 2000 issue about a new secretary's office at Shelsley Walsh itself,…

Matt Kenseth and Jack Roush’s Roush Fenway Ford team may have been the only happy people in Daytona on Sunday night. Kenseth scored both his and Roush’s first Daytona 500…

Renault has unveiled a sneak peak of its 2020 Formula 1 car ahead of winter testing next week with digital renders of its new effort. The R.S.20 was partly shown…

Max Verstappen and his fellow competitors are against the idea of a driver salary cap considering they risk their lives for the sport

With more factory-backed teams than customers and a ruleset that rewards integration, 2026 could mark Formula 1's return to a manufacturers' championship