The two would work all hours, rush down to prepare the Lotus 11 Parkes was racing, then back to work, then race. Non-stop. Mike was also kept busy with girlfriends who tended to live in London while he was based in the Midlands. “He’d nip down there in the evening, come back in the early hours. Once he put his E-Type in a ditch through fatigue,” Fry recalls.

Parkes’ ability on the track meant people began offering him rides, notably Tommy Sopwith, whose Ecurie Endeavour team ran a squad of Jaguar MkIIs for him, Graham Hill and Jack Sears. This led to a highly successful association with Colonel Ronnie Hoare and the Maranello Concessionaires Ferrari 250GT.

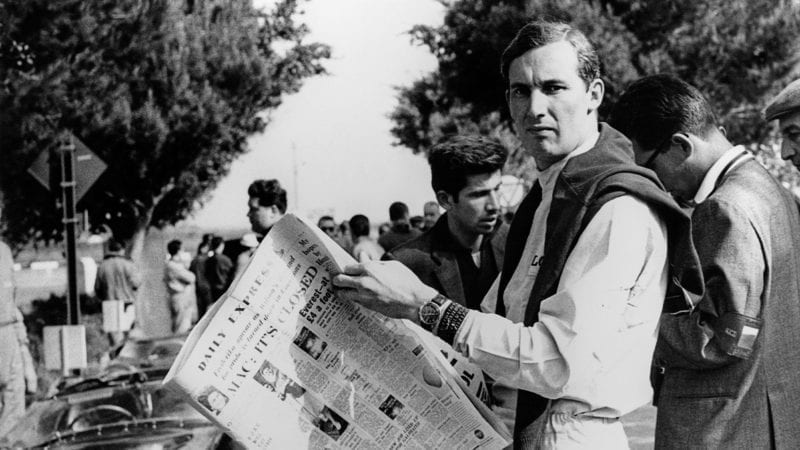

When Parkes went to Le Mans in ’61 to over see the Rootes team of Sunbeam Alpines, he was invited by Ferrari to try a works 250GT. Still dressed in flannels, collar and tie, he was instantly quicker than the regular drivers, was offered a drive in a 250TR for the race and finished second with Willy Mairesse. His affair with Ferrari had begun. At the end of ’62 he left Rootes for a full-time position at Maranello as a development engineer cum race driver.

Delighted though he was, the language barrier meant he was lost outside the factory. Brenda Vernor was teaching English to Italian students locally, and Parkes sought her out to help with his correspondence.

“I first saw him,” she says, “sitting in the sitting room at the house where I was boarding. I felt sorry for this tall, slim, good-looking man sitting by himself, unable to converse with the family of the house.

“The arrangement suited me because I was free from school most evenings and it gave me some little pocket money, though over the years our relationship did become more than boss/secretary, after which I wasn’t paid anymore!

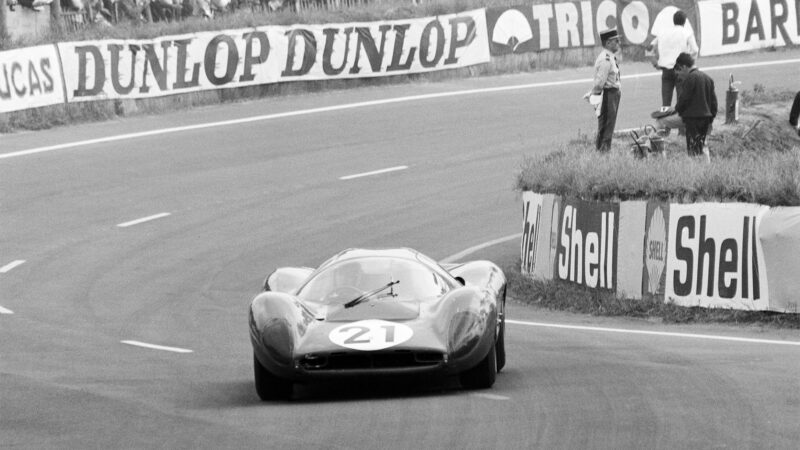

1967 brought another runner-up finish at Le Mans driving the Ferrari 330 P4

DPPI

“Deep down he was very sensitive but he also had a wonderful sense of humour, especially when he was racing with ‘Lulu’ Scarfiotti and Lorenzo Bandini – they’d get up to such pranks. Most of the people he worked with at Ferrari, other engineers and mechanics, loved him.”

Indeed the Commendatore himself came to form a rare bond with him. Some even said Parkes had unofficially become Enzo’s right hand man. “There was a definite spark between them,” says Annabel Parkes. “I think it might have been because he was more than a driver – he was in the factory every day. There was a lot of joking. Mike introduced me to him as his sister and Mr Ferrari said ‘what, another one?’ and Mike replied ‘no, this really is my sister.’”

It should have been the dream job for Parkes and certainly he was happy, but a part of him remained unfulfilled. Even though he had spent over a decade in love with his work as an engineer at Rootes and racing only as a side line, by his mid-30s he had become more ambitious about his driving. Emboldened by a tally of victories in sportscars – the Sebring 12 Hours in ’64, Monza 1000km in ’65 and ’66, the Spa 1000km in ’66 – he yearned for an F1 chance and campaigned heavily to the boss. It smacks of a conflict between the driving and engineering sides of him; he could do both, but being ambitious in one tended to take him away from the other. The equilibrium was disturbed, and the fall-out was volcanic.