Readers' letters, October 1983, October 1983

Comfort at the wheel Sir, AH's comments on the lack of space in the Rover Vitesse highlights a trend that is making life very difficult for people who, like me, are over…

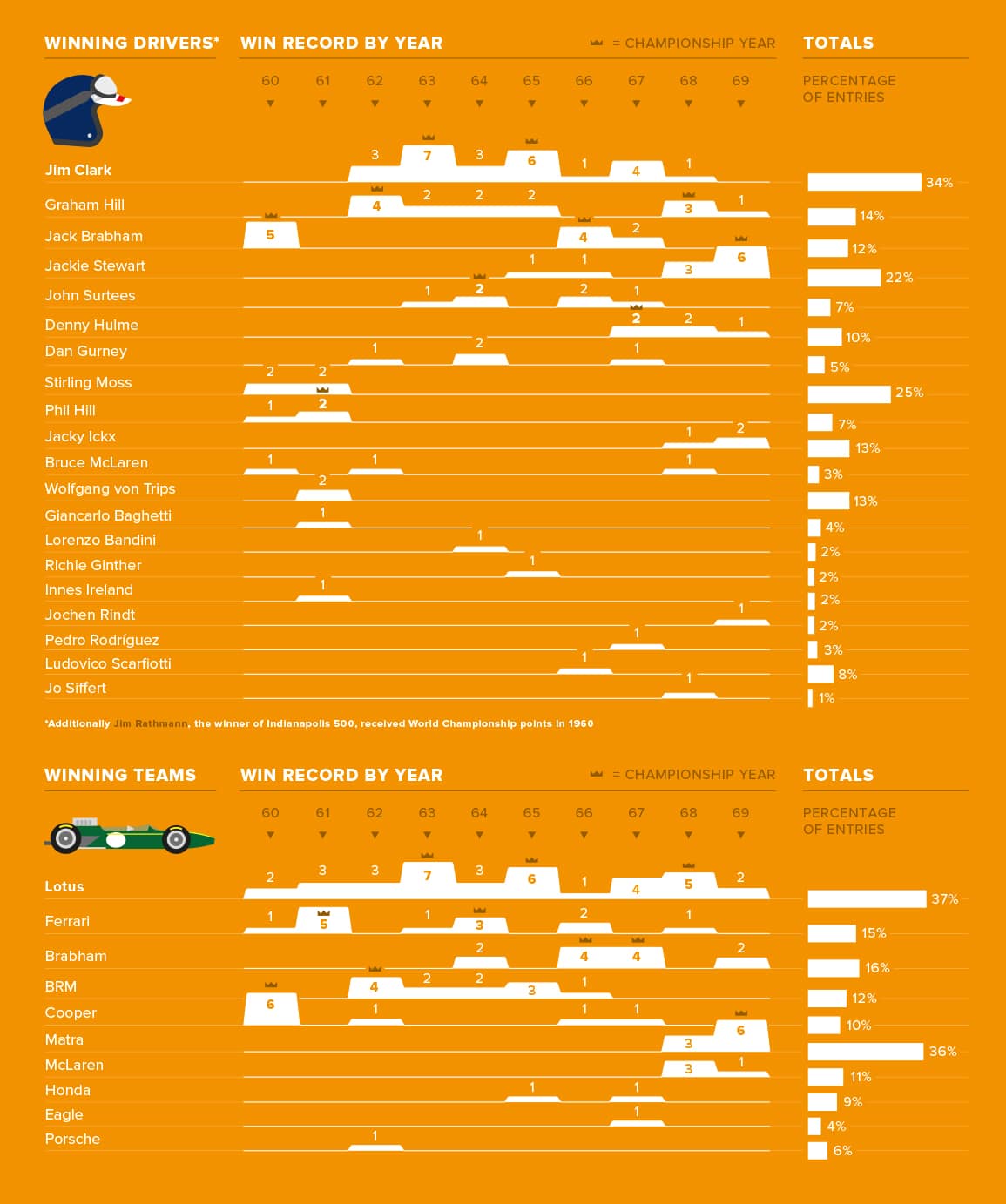

The 1960s belonged to Jim Clark and Lotus, but his death in ’68 would rock F1 to its core

Getty

Looking back, we were very spoiled in the 1960s. Whether it was the music or the movies – or the motor racing – there was a feeling of enchantment in the air. In a single month in 1967 I moved to London, bought Sgt. Pepper the day it was released, and saw Dan Gurney and AJ Foyt win the greatest Le Mans 24 Hours. Good times.

Not entirely, though. A couple of weeks beforehand, Ferrari’s Lorenzo Bandini had died hideously at Monaco, trapped under his car when it caught fire following a crash at the chicane. This was the other side of the racing coin. If the cars of the day, shaped by designer’s pen rather than wind tunnel, were a delight to the eye and the ear, thanks to a plethora of V12s, little attention was paid to driver safety. Carbon fibre was still way in the future. In the race that cost Bandini his life, only one driver, Jackie Stewart, went to the grid wearing seat belts.

Stirling Moss considered his ʼ61 Monaco GP victory the finest of his career

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Stewart had a bad accident at Spa in 1966 in which he hit a telephone pole at 170mph at the Masta Kink and had to be extracted from his BRM P261, receiving substandard assistance. Stewart then took it upon himself to change the whole thinking about safety, but he was long reviled for his campaigning. It was as if some believed it wasn’t quite manly, somehow. As it is, every driver of the past 50 years is in his debt.

As the 1960s began, Formula 1 was radically changing. In 1960 Moss was victorious at Monaco in a Lotus 18; only four years earlier he had won there in a Maserati 250F.

John Cooper had swung a lamp over the future: the place for the engine was behind the driver, and even Enzo Ferrari, who had sworn to Cooper in 1959 he would never build a rear-engined car, produced one the following year. It made a single exploratory appearance, but it was the foundation of the shark-nosed cars that would dominate in 1961.

Jack Brabham set new records in this era, winning a title with his own chassis design

Getty

If the concept of the car was changing, F1 remained fundamentally simple, as Cooper – in whose car Jack Brabham won the first World Championship of the decade – recalled. “In those days ‘sorting’ a car meant getting gear ratios right and trying alternative roll bars. Sometimes we’d play with different wheel off-sets and so on, but that was about it!

“Stirling thinks Monaco 1961 was his greatest drive, and the raw statistics of that race beggar belief”

“Formula 1 was pretty cheap then. We’d build a chassis for £3000, a whole car for four grand. Like most teams, we used Climax engines, which were £1250 apiece, and we’d do at least two race weekends without stripping them down. So far as ‘sponsorship’ was concerned, in 1960 we got £10,000 from Esso, a couple of thousand from Dunlop, a grand from Champion, and that was the lot.” We are talking, of course, of a dozen years before Bernie Ecclestone took over F1, founding FOCA (the Formula One Constructors Association), which – although the word ordinarily made him quake – unionised the teams, on whose behalf Ecclestone dealt with race organisers.

“Bernie made a lot of people rich, didn’t he?” Cooper smiled. “In a way, we could have done with him in those days – but, then again, it was when the big money arrived that the fun started to go out of it.

Battle for ’61 French GP victory goes to the wire; Giancarlo Baghetti (50) won

Getty

“We used to negotiate individually with each race organiser and, in our case, the ‘starting money’ was around £1000 a car, which was split 50-50 between team and driver. First prize money in a grand prix was always about a grand, of which the mechanics would get 10 per cent. We’d take only two or three to the races, and they had to drive the transporter and everything, then come back and rebuild the cars! They didn’t have it easy, those boys…”

If Cooper dominated 1960, Ferrari swept all before it the following year, in which Giancarlo Baghetti became the only driver to win on his grand prix debut, doing so at Reims. There and elsewhere, the team’s power advantage was such that only at Monaco and the Nürburgring could the genius of Moss defeat them.

Stirling thinks Monaco 1961 was his greatest drive, aboard the Rob Walker Racing Lotus 18, and the raw statistics of that race beggar belief. His pole time was 1min 39.1sec, and in the race – 100 laps back in the day – his average lap time was 1min 39.5sec. Towards the end, still under pressure from Ferrari, he lapped almost three seconds inside his qualifying time! ‘Mr Motor Racing’ they christened him, and they were right.

Graham Hill, here driving his BRM at Brands in ’64, would win two titles in the ’60s

Getty

If today driver contracts can take months to finalise, life was simpler then: “Stirling and I never had a contract,” said team owner Rob Walker, “just a handshake at the beginning of every season.”

Assuredly Moss, who raced virtually every weekend of the season, earned more than his rivals.

“My best year was 1961 when I made £28,000 – about the same as a top lawyer. Mind you, I had to pay my own expenses out of that – I paid tax on about eight grand.”

The others, said Phil Hill, were nowhere near that. “Stirling was savvier than the rest of us. In all my years at Ferrari, my road cars were Peugeots! Whatever else, no one could be accused of doing it for the money, because there wasn’t any. And in the same way, safety was never discussed – because there wasn’t any of that, either!

Fettling a Ferrari 158: the 1.5-litre V8 marked F1’s return to contention

Getty

“There was more fun back then, but there was a flip side, too. You had people on the outside posing these questions: ‘How can you do this? Your friends are dying, and yet still you do this…’ In that respect, it was little different from wartime.”

In 1961, Hill’s win at Monza clinched his World Championship, but that same day Wolfgang von Trips, his Ferrari team-mate and rival for the title, was killed in an accident which also took the lives of 14 spectators. If that seems scarcely believable today, track safety was primitive, with trees in abundance, barriers and run-off areas unknown.

Invariably, drivers travelled together on commercial flights, further strengthening the sense of camaraderie that then existed, not least because life was tenuous. In the course of the 1960s, 17 top drivers died at the wheel.

In 1962, Moss came within an ace of being among their number. For reasons never clearly established, his Lotus crashed at Goodwood on Easter Monday and, although he ultimately recovered from devastating injuries, at 32 his career was over. The torch passed – as it always must – to Jim Clark. Whenever one thinks back to the 1960s, it is he who first comes to mind.

Chris Amonʼs new Ferrari rear wing catches the eye in the paddock at Spa

in 1968

Getty

“Like Fangio and Moss,” said Stewart, “Jimmy was the best of his generation – and he never knew how good he was…” Perhaps the statistic that says most about Clark is that only once did he finish second in a grand prix. As he scaled the heights, so did Lotus – the only team he ever drove for. Sometimes there was a challenge from such as John Surtees, Graham Hill or Dan Gurney, but usually, Jimmy was in a race on his own. World Champion in 1963, he won the title again in 1965, clinching it in August with his sixth win, at the Nürburgring.

That race was the seventh of the year, but Clark had missed Monaco. He was at Indianapolis that weekend, winning the 500. “Made him very happy, that did,” a Lotus man chuckled. “The car won $166,000 (£127,209), and Jim got a good chunk of it – when Colin [Chapman] was paying him eight grand a year for Formula 1…”

The best on Earth he may have been, yet Clark remained a shy and modest man. There were no motorhomes to hide in, and when I walked into the Silverstone paddock one morning in 1965 (for a couple of quid you could buy a pass) he was the first person I saw. After signing my programme, he started chatting: “Was this my first grand prix?” No need for a ‘Fan Experience’ in those days. As well as that, because there was little TV coverage, the drivers retained an exotic, mysterious quality. Beyond a few words over a circuit’s PA system, you never heard the voices of Jochen Rindt or Pedro Rodríguez, much less saw them playing infantile games for the camera.

There was a romance about that era, and it came in part from a continuing sense of history, with grands prix still run at traditional theatres of battle such as Spa, the Nürburgring and Rouen Les Essarts. Save at Monaco, the word ‘chicane’ was as good as unknown.

“I couldn’t help but wonder what can of worms we were opening with downforce”

Through the first half of the ’60s, when the 1.5-litre formula was in force, the cars may have been small and underpowered, but they raced superbly: with downforce not yet thought of, a car’s ultimate cornering speed was dependent on the delicate throttle control of the driver above all else. The 1966 season, trumpeted as ‘The Return to Power’, was the dawn of 3-litre F1, and it was welcome. Now the cars had more power than grip. With opposite lock evident, it was a fine time for spectators. Now in a car bearing his name, Brabham took his third World Championship.

The following season Ford came into F1 and changed everything. For years the company had toyed with the idea, but no one took it seriously. “In 1961,” John Cooper remembered, “I met Lee Iacocca, the guru of the American motor industry, and said, ‘I hear you might be coming into Formula 1’. ‘No,’ he said, ‘Ford’s not interested in Formula 1 – we’re gonna go the whole hog on grand prix racing!’ I didn’t pursue it any further…”

Now Ford was bankrolling the greatest engine in F1 history, the Cosworth DFV V8. It made its debut at Zandvoort in the new Lotus 49. Clark, experiencing both for the first time, duly won. If Denny Hulme’s ultra-reliable Brabham took the title, and the ‘twelves’ – from Ferrari, BRM, Honda, and (Eagle) Weslake – still had their days in the sun, Keith Duckworth’s masterpiece set new standards.

Mario Andretti drives the red and gold Lotus 49B at Watkins Glen in ʼ68 as

F1 sponsorship grew

Getty

Ken Tyrrell, then running a Formula 2 team, had thoughts of moving up, and that first victory for the DFV made up his mind.

“I flew to Zandvoort for the day to watch, and it was clear that the DFV was the only engine in the race – if you wanted to do F1 in the future, this was what you had to have.”

In 1967, only Lotus had the DFV, and Chapman was livid when Ford subsequently made it generally available the following year. Like Bruce McLaren, Tyrrell was an immediate customer: running a Matra for Stewart as his fledgeling team won three races in 1968.

“You went to Northampton,” said Ken, “you gave them £7500, and you came away with an engine that could win you the next race – and it continued like that for years. Almost impossible to believe, but that’s how it was.”

Stewart said: “Being available to anyone, the DFV meant that most of us had the same horsepower, so it couldn’t have been more different from today. It brought F1 to a level it had never reached previously – and that I don’t think it has ever reached since.” For 17 consecutive seasons, it would win grands prix, with a final tally of 155 victories.

In the 1960s, the life of a grand prix driver was very different from the modern-day. There may have been fewer Grandes Epreuves, anything between eight and 11, but non-championship races abounded. Additionally, not least to supplement their incomes, drivers competed in various F2 and sports car races. Hence life could be busy. In August 1967, F1 made its first visit to Canada, where Brabham won. Having collected his cheque ($10,575), Jack – together with Rindt, Stewart, Hill and Chris Irwin – then dashed away for a ‘red eye’ flight to make the Bank Holiday F2 race at Brands Hatch. They were graciously allowed a practice session in the morning, after which Rindt won, with Stewart second. In 1967, who needed sleep?

I always think of it as F1’s last simple year. For one thing, downforce entered the paddock vocabulary for the first time the following season. At Spa, Chris Amon’s Ferrari arrived with a tiny rear wing – and took pole position by four seconds. “I couldn’t help but wonder,” Amon said with some prescience, “what can of worms we were opening here…”

“Rather than rant, at Christmas Graham sent Lorenzo an LP of advanced driving lessons…”

It was in 1968 that commercial sponsorship made its entrance. At Kyalami, Clark’s victorious Lotus was in traditional green and yellow, but by the next grand prix, Jarama, the livery of Graham Hill’s winning car was the red and gold of a Player’s cigarette packet.

Purists didn’t like it, but on their minds was a more visceral shock: Clark, the grand seigneur, was gone, killed in an F2 race at Hockenheim. On the grid at Silverstone’s International Trophy, the drivers observed a minute’s silence in his memory. The impact of the loss of Clark was profound.

“People used to get killed quite often back then,” said Amon, “and of course there was always grief, but the loss of Jimmy had another dimension to it – if it could happen to him, what chance did the rest of us have? At Jarama, I was on pole, but all I could think of was a grand prix without Jimmy Clark. We all felt we’d lost our leader.”

At the time of his death, Clark was about to return to Scotland, having spent a year in Parisian tax exile, unusual when drivers earned thousands rather than millions, but understandable given the high-income tax regime of Harold Wilson’s Britain.

Stewart, indeed, had gone further, buying a house in Switzerland and putting down roots. “It had occurred to me,” Jackie said, “that, nine weekends out of 10, I was risking my life for the Chancellor of the Exchequer…”

Stewart became the man to beat. Although narrowly beaten to the championship by Hill, in appalling conditions at the Nürburgring Stewart won by an astonishing four minutes, and the following year cantered to the title in what would become his favourite car, the Matra MS80.

By now his main opposition came invariably from Rindt, and at the 1969 British Grand Prix the pair of them put on a battle for the ages.

Jackie & Helen Stewart, Grand Prix of Great Britain, Silverstone Circuit, July 19, 1969

Getty

“There was as good as no difference between Jochen and me,” said Stewart, “and it was the same with our cars. The great thing about racing in that era was that it was hard, but also clean. There was no weaving or blocking – we didn’t mess around with any of that stuff; apart from anything else, if we had, obviously the others would have got closer, wouldn’t they? At Silverstone, we overtook each other umpteen times…”

At Monza, Stewart again beat Rindt’s Lotus, this time by mere inches. The last championship of the 1960s was settled, a golden age in F1’s history done and dusted.

Five years earlier, three British drivers – Clark, Hill, Surtees – had gone to the final race in Mexico to settle the championship. After Jim retired from the lead on the last lap, John took the title, Ferrari team-mate Bandini waving him by for the points he needed.

Earlier in that race, the Italian had accounted for Hill, ramming him at a hairpin. One hesitates to imagine the fall-out from such an incident in today’s F1 – the World Championship was at stake, after all. But everyone, including Hill, knew that Bandini had simply made a mistake. Rather than rant, at Christmas Graham sent Lorenzo an LP of advanced driving lessons…

A more violent time it may have been, but a more stylish and generous one it undoubtedly

1960 Phil Hill (Ferrari 246) is last driver to win WCGP in front-engined car (at Monza, boycotted by leading UK-based teams on safety grounds). Brabham takes second title. Indy 500 makes final appearance on WC calendar.

1961 Race-winning driver now gets nine points; constructors do so in 1962. Ferrari on top for new 1.5-litre engine regs (forced induction banned) and Phil Hill becomes the first American World Champion.

1962 Ferrari fades, Colin Chapman shifts design goalposts with monocoque Lotus 25; Graham Hill clinches title in South African finale. Accident at Goodwood ends Moss’s front-line career.

1963 Clark and Lotus dominate with seven wins from 10 grands prix.

1964 Clark set to be champion, but engine seizes in finale. Lorenzo Bandini cedes to John Surtees, who becomes first and only driver to win world titles on two wheels and four.

1965 Clark skips the Monaco GP to win the Indy 500, but still clinches his second World Championship.

1966 ‘Return to Power’, with 3-litre engines (or 1.5-litre forced induction, with which nobody bothers). Brabham-Repco is the car to beat; Jack Brabham becomes the first driver to win the title in a chassis bearing his own name.

1967 Cosworth DFV appears for the first time in Lotus’s 49, but patchy reliability blunts the team’s challenge. Denny Hulme succeeds team-mate Brabham as champion.

1968 Graham Hill becomes the first DFV-powered champion, for the (Gold Leaf-branded) Lotus team left reeling by Clark death’s in an F2 accident.

1969 His chances hampered by injury from the previous season, Jackie Stewart takes the title in a Matra run by old Formula 3 mentor Ken Tyrrell. Tall wings banned after a series of failures. Four-wheel drive isn’t new to F1, but it becomes a fad… briefly.