The car was launched in April 1976. Derek Bell was called upon to drive and to this day he shudders at the memory of the unveiling. “I stood there as the covers came off and could hear this voice saying, ‘This is the car with which we will win the European Touring Car Championship round at Salzburgring in three weeks.’ I could not believe it. The car was completely undeveloped yet this PR man said we were going to show BMW how it was done. Ludicrous.

The problems were legion. Broad remembers the driveshaft failures most, Darley the tyres rotating on their BBS split rims. Bell’s memory is of endless engine failures due to oil surge from its too small, too shallow wet sump while John Fitzpatrick, the quickest by far of all who drove the car according to Broad, remembers a tyre exploding at 180mph during the Brno round in Czechoslovakia. Odd then, that everyone I spoke to, has such happy memories of the car.

Very odd from where I’m sitting. The truth is, the Broadspeed Coupe is now a museum piece and, bolted into its driving seat, looking at the walnut dashboard, I wondered from which century. The engine had an appalling misfire and I sat with the left foot on the clutch, right on both brake and throttle to keep the motor alive and stop the car slipping back. Green light.

Clutch in gently and a little bit of throttle. The Jag limps pathetically forward, more chance of guessing the lottery numbers than how many cylinders are firing at any one time. Suddenly at least 10 chime in and instantly we’re sideways on the damp tarmac. Off the throttle, gather it up and we’re limping again. Change into second and, inexplicably, the engine starts to pull. At 5000rpm, I hear the 12th cylinder cut in and, for the first time since we left the start line, the Broadspeed is running as it should. V12 music blasts out at huge volume from the four stub exhausts under my door, there’s monumental thrust and then we’re sideways again.

Round it up, stagger through two corners onto the straight, rocket up to 7000rpm, change into third — and half the cylinders quit again.

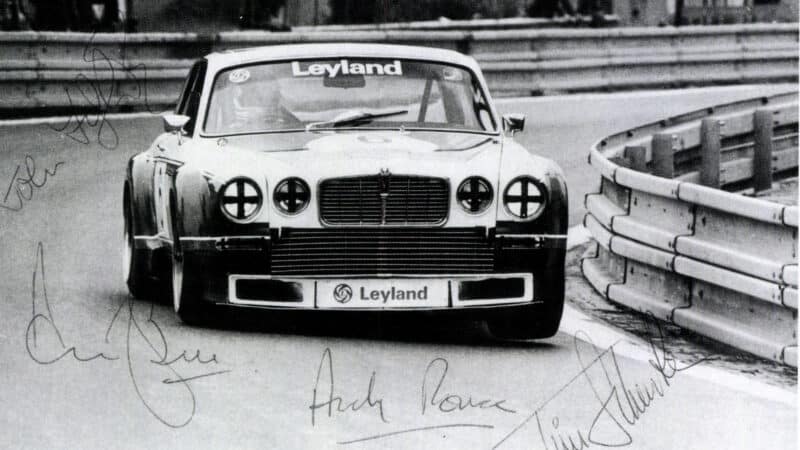

The bevy of BMS CSLs couldn’t hold a candle to the Jaguars in terms of outright pace, but enjoyed the admirable quality of being around when the chequered flag fell — Zandvoort a case in point

LAT

It was not always like this. Fitzpatrick’s memories of the car, while it ran at least, are universally rosy. “It was a big, heavy car for sure, but when it worked, it really worked. Quickest thing out there by a mile. Of course, it had a lot of power but you don’t leave the entire field at 13 seconds a lap around the Nurburgring just by being quick on the straight.

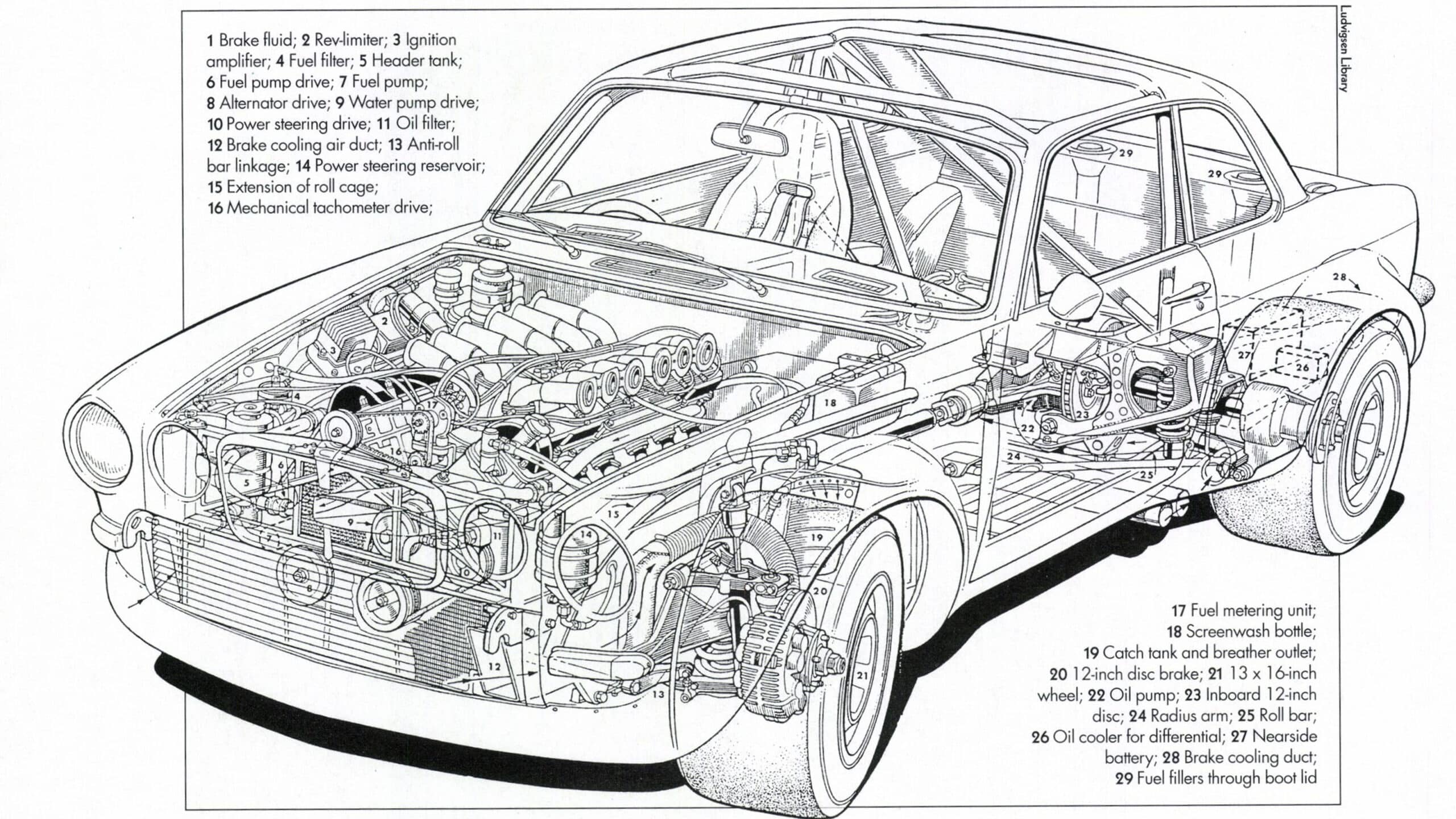

“Really, it was capable of destroying the opposition. The only area where the BMWs were noticeably better than us was under braking.” This was no surprise as the highly-developed BMWs sat right on their 1050kg limit while no Broadspeed Jaguar ever saw the sunny side of 1400kg. Yet through the corners, there was nothing in it, as Fitzpatrick confirms.

“The press and public had such high hopes for the car but I knew it was never going to last”

“We could stay right with them. The car was heavy but it didn’t feel that way. Ralph’s team came up with excellent suspension geometry and even without power steering, it never felt heavy to chive. You could do things you’re not supposed to be able to do with such a big heavy car. You’d think long and hard before really starting to drift and slide such a heavy machine through quick corners, but we soon learned you could with the Jag. It had absolutely no vices at all in that respect and you could lean on it very hard indeed without it ever biting.”

So long, of course, as the wheels stayed on. Far from winning at the Salzburgring in May 1976, so plagued were the early days of the car that it did not make its race debut until the Silverstone TT in September.

“It was quite sad, really,” Bell remembers. “The press and public had such high hopes for the car but I knew it was never going to last.” It won pole position and Derek duly scorched off into the lead, dicing with Gunnar Nilsson’s BMW. Brake trouble and a tyre deflation sent Bell down the order before he handed over to David Hobbs, who fought hard until a hub flange failed and a wheel came sailing past. The Broadspeed Coupe did not race again that year. By the time the 1977 season started at Monza, there were two Coupes and a raft of performance-enhancing modifications, including huge 19-inch wheels and commensurately vast Dunlop slicks. If anything the cars, now driven by Bell/Andy Rouse and Fitzpatrick/Tim Schenken, were faster still. But all the extra grip played havoc with a wet sump oil system already taxed well beyond its design, and a lack of spare engines meant Bell and Rouse did not even start. The one surviving car secured pole position but barely completed the first quarter of the four-hour race.

At Salzburg, things looked up — briefly. Pole was again claimed before both cars retired, again with more failed hub flanges. The cars failed to appear for the next two rounds, at Mugello and Enna, but they were back at Bmo in June, the slower of the two cars six clear seconds a lap faster than the swiftest BMW. The Jaguars duly lined up next to each other on the front row. Bell’s engine lasted barely more than a lap. Fitzpatrick’s race ended effectively with another mighty tyre deflation, though the car did finally finish 16th, its first result.

The Nurburgring was different, though it started the same: despite endless problems in practice, Fitzpatrick claimed pole, and from the standing start, he set a new lap record that would not be approached again during the race. He blew up on the next lap. Bell and Rouse played a different game. “Odd as it may sound,” says Derek, “we decided not to try and beat the BMWs. We just sat there, didn’t push the car and came second.” It was the first and only podium finish the XJ12C would achieve.

The next race at Zandvoort would be the only time the team were not to claim pole, for wet weather handed the qualifying advantage to the CS Ls ; in the race both Jags retired again.