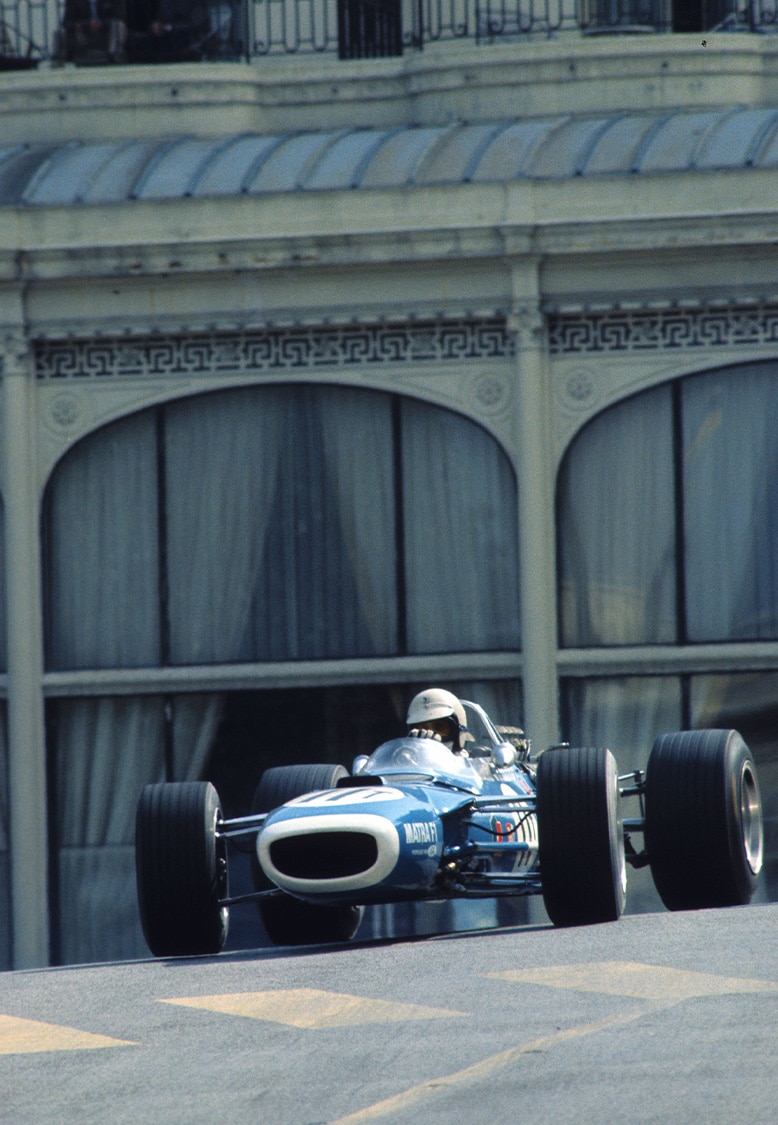

The following day they lined up side by side, and at the fall of the flag the Matra was first away. Probably it was wisdom and experience that kept Hill from following too closely, and they served him well. For three laps Servoz ran away from the pack, but on the fourth he abruptly slowed, left-rear suspension broken. Although Johnny still insists he never hit anything, onlookers at the chicane were adamant his car had kissed the barrier at the exit. Whatever, the Matra retired at the pits, with Tyrrell stony-faced, his driver ready to weep.

Servoz was one, it seemed to me then, absolutely right for his time. If the name looked great on the side of a cockpit, so also the man looked the part. After an era in which too many F1 drivers for my taste, anyway were to be seen pushing prams around paddocks, Johnny had the freewheeling ways of my childhood heroes. He was a throwback to Alfonso de Portago, a reminder that not all racing drivers lived like monks. Servoz, emphatically, did not live like a monk. “I always liked the girls,” he said, which is a little like saying Michael Schumacher is quite quick. Johnny also liked to eat and drink well — liked the good life, in fact.

A playboy, then, and something of a hippy, too. This was the late ’60s after all, and his hair was fashionably long; he was also years ahead of the game when it came to designer stubble. Very louche, in a James Dean sort of way, but not contrived. Simply, he seemed like a free spirit who had found the perfect job. The abiding problem was that he lacked the commitment to do justice to his talent.

Johnny made amends for his Monaco disappointment by finishing second at Monza. But he was soon lost to F1

DPPI

Despite the setback at Monaco, Tyrrell occasionally entered a second Matra for Servoz in ’68, and at Monza he took a fine second behind Denny Hulme. There was no question of a drive with Ken for 1969, though, for Matra were keen to ‘place’ Beltoise in the Tyrrell-run team until ready to return with their own factory outfit the following season. That year, therefore, Johnny concentrated on F2, and clinched the European championship with a victory in the last race, at Vallelunga. For 1970, Tyrrell hired him as Stewart’s permanent number two. He looked set.

Then, one day that winter, he contested one of those curious semi-rally events, so beloved in France, for such as Jeeps and Land Rovers. It was fun, nothing more, but in some woodland, a small branch caught him in the right eye. Aware of the possible consequences for his career, Servoz initially said nothing. He had treatment in hospital, stayed in a darkened room for five weeks, and hoped.

In the early races of 1970, though, the old panache and the pace were gone. Of course it didn’t help that Tyrrell was now running a pair of agricultural March 701s, rather than Matras, but Stewart certainly made the most of his, winning the Spanish Grand Prix at Jarama. That same day, Servoz was fifth, two laps down, the last man to finish.