“Bob drew the new upright,” remembers Head. “Quite simple, but it was drawn in half a day. Thirty-six hours later, two aluminium castings to the new design were delivered. Six hours later, they came out of the machine shop. Two hours later, they were on the car. New bodywork was delivered from Specialised Mouldings and the car was transported to the USA, less than three days after the change had been initiated.”

Three days. A completely redesigned race car from the cockpit forward. Even at the end of a long career in motor racing that saw him become one of the most successful designers in F1 history as co-founder of and technical director of the Williams Formula 1 team, it remained one of the most remarkable things with which Head had been involved.

At Mosport, Stewart planted the freshly reconstituted T260 on pole by seven-tenths of a second over Denny and Peter. Oh, not that Peter. The other one, Revson. Over the winter, McLaren had decided to replace the jockey-sized Gethin in Can-Am with matinee-idol Revvie. Twenty-six cars in all would start the race, but for all intents and purposes, these were the only three cars that mattered. Next was Canadian John Cordts in an older McLaren M8C, more than two seconds behind.

Baulked by a sticking throttle, the Mod Scot polesitter watched Hulme lead the early laps. By lap 10, he’d come to terms with the issue and put the cigarette box in front. Nine laps later, the Lola rolled to a stop, its differential seized.

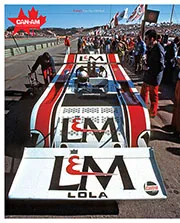

Watkins Glen brought more disappointment

Getty Images

It would be the story of the season.

At Mont-Tremblant Denny put the McLaren on pole, but Jackie was right beside him. Again, Hulme shot into the lead. Again, Stewart found a way by, this time aided by the fact that Hulme was battling a stomach virus. By the end of the race Stewart had scored his first victory in the T260 and McLaren had been vanquished for only the second time since 1968.

On to Road Atlanta the circus went, and here Stewart was at his most masterful. This time the Lola was a full second from pole, but when the flag fell, Stewart seemed to find reserves of speed only he could. He passed Hulme on lap three, Revson on lap eight, but a deflating tyre forced him to pit on lap 13, dropping three laps down. The race was over, but not the spectacle. The normally silky-smooth Stewart began flinging the T260 around the track at impossible angles, scrabbling for every last speck of grip.

Barry Smyth, doing PR for the rival McLaren team, still sounds awestruck: “He looked like a sprint car driver, he had it hung out so far. He just drove the wheels off that car.”

“Stewart got the absolute maximum out of that car,” says Marston. “I think at that time he was absolutely at his driving peak.”

Stewart was considered racing’s No1 by 1971

Grand Prix Photo

Stewart ultimately set the fastest lap, 0.3sec faster than Hulme’s pole time. It also equalled precisely the time the Chaparral sucker car had set the previous year. In the end, it was the Lola that gave up, not the Scot. The T260 limped into the pits on lap 62, its right rear shock having tapped out.

By the next race it was clear the orange cars’ fifth straight title was safe. There were two of them against one Lola, and Stewart fell too far behind in the points race due to mechanical issues to make up the deficit. At the Glen, Stewart once again put the T260 on pole. Once again, the car let him down.

Stewart had managed to lead all four races to date in a clearly inferior car but only finished one of them. “The car was extremely difficult to drive,” he recalls. “It had a very short wheelbase and the aerodynamics… I don’t think there was a wind tunnel being used, it was just a wet finger in the air, I think.”