Elford first came into contact with the 2J when competing at the Can-Am Watkins Glen round for Porsche. The Brit and his fellow competitors found the 2J as baffling as it was breathtaking.

“I think we all just thought ‘Jesus Christ, how the hell does that work?’ he recalls, “I mean I’d seen some of Jim Hall’s creations before, [but] I guess we were all a bit shocked!”

In an age when the designs of other Can-Am vehicles might be described as fantastical, the 2J was somehow shockingly functional in its space-age tendencies. The plain liveried car, with its lightweight fibreglass body which covered the rear-wheels before being brutally cut off at the point where the turbines emerged, was described by Motor Sport’s David Gordon as “the big white shoebox”.

GM had pulled in one Jackie Stewart to pilot the 2J for its debut at the Glen. In his book Faster, the Scot was wide-eyed in his description of the car’s capabilities.

“The car’s traction, its ability to brake and go deeply into the corners, is something I’ve never experienced before in a car this size or bulk,” he said, “Its adhesion is such that it seems to be able to take unorthodox lines through turns, and this, of course, is intriguing.”

Certain components couldn’t take the strain of the loads they were put under. After problems in qualifying with the auxiliary engine (which was being run full-throttle the entire time) meant the car couldn’t exploit its full downforce potential, Stewart then retired from the race with brake failure – but only after setting the fastest lap.

“Adapting to it mentally is difficult because no other car has gone around a corner this fast”

After the race, Elford received a phone call from the Chaparral boys, who were coincidentally staying at the same hotel as him.

“I went to Jim’s room. He said to me ‘Well, you saw the Chaparral today. Would you like to drive it?’ I replied, ‘C’mon Jim, you’ve got Jackie Stewart driving!’

“He said: “That was just a one-off PR thing with General Motors. We now need a proper driver for the rest of the year. We’ve been looking at people and we think you’re the best one that we’ve seen out there – to understand the engineering, work with the engineers, and drive the car into the bargain. So how about it?’

“And I said ‘Of course, love to. Thank you very much!’ So that was how it all started.”

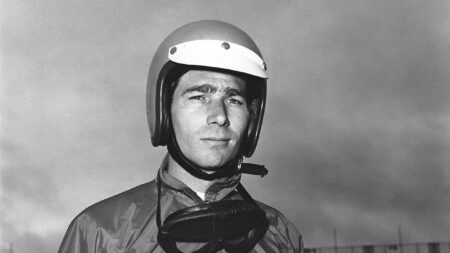

Vic Elford at the wheel of the Chaparral 2J at Riverside

Fred Enke/Getty Images

Chaparral’s newest driver flew out to Midland, Texas to start testing the car. The sleepy desert town was home to Chaparral’s workshop and also their bespoke testing track – Rattlesnake Raceway.

In spite of the wide variety of machinery he’d already sampled, the Chaparral 2J was like nothing else Elford ever encountered.

“Driving the car was just out of this world,” he says, “The [start-up] procedure was a bit like an aeroplane I suppose. You didn’t just jump into first gear and drive away.

“I would put my left foot hard on the brake to make sure it didn’t go anywhere. Then I would fire-up the little engine which would immediately start to drive those two monster fans at the back, sucking up the air underneath.

“When I did this the car would literally go: ‘Shhhp!’ and lower itself down to the ground by about two and a half inches.”

Such was the sucking power of the turbines, the car would move of its own accord at about 30mph, hence the driver needing to have his foot on the brake throughout the start-up procedure.

“I drove around the outside of Denny in third gear. He went into the pits and sulked for the next half an hour.”

The new driver/car combination’s first race was at Road Atlanta, Round 6 of the 1970 Can-Am season.

Despite its obvious promise, the car had so far only driven a few laps in competitive anger. In Motor Sport’s race report at the time, Elford described the challenge of driving such an ‘easy’ car:

“You get to the stage of thinking that it’s just not possible that the car can go around any corner at that speed,” he said, “and adapting to it mentally is the most difficult approach because no other car has ever gone around a corner as fast as this one… Another great thing about the suction is that it doesn’t allow the car’s handling characteristics to change as you go through a corner … Whichever way it’s set it remains like that at all times, whether it’s a slow corner or a fast swerve – it remains absolutely constant”.

Elford’s eventual confidence in the car translated into pole position for the race, taken by 1.26sec ahead of McLaren’s Denny Hulme.

Come race day though, it all started to fall apart. Chaparral’s sluggish getaway at the start didn’t help.

“The problem was I only had a three-speed gearbox,” Elford explains, “They [Hulme, McLaren’s Peter Gethin and Lola’s Peter Revson] all had four. Although I was way out [in first] on the starting grid with a rolling start, they all went by me at the startline.”

A sub-1 minute lap at Laguna Seca was easily enough for pole at Laguna Seca

Fred Enke/Getty Images

Ignition issues put the 2J out but things were looking good for the next round at Laguna Seca.

Elford didn’t disappoint, taking pole once more. On this occasion, it was an even bigger margin of 1.8sec despite the Monterey circuit being particularly short. The Chaparral’s drubbing of the opposition was described by Motor Sport’s David Gordon as a “demoralisation process”.

“I went around [Laguna Seca in] 59sec and it was about five years before the next car managed to go under a minute – and then that was an IndyCar anyway,” says Elford.

However, come the warm-up, reliability gremlins struck again. This time, the Chevrolet engine fell on its own sword as a connecting rod punched a hole through the block.

“I remember people coming up to me, throwing their arms around me, sobbing in the paddock and saying, ‘Please go and change the engine, it only takes a couple of hours to change a Can-Am engine!” Elford remembers, laughing.

“And it probably did in a McLaren. But it took all day in a Chaparral, because you had to literally take the whole damn car apart!”